Christmas—the celebration of it, at least—has changed a lot in the last 180 years or so. Most of us have never had figgy pudding. We don’t put real candles on our Christmas trees, lest we burn the neighborhood down. Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer wasn’t even a crimson glimmer back then.

But Scrooge? Marley? Tiny Tim? They’ve been with us since 1843. They’re longstanding Yuletide visitors, a part of our Christmas experience in our own pasts, presents and yet-to-comes. And by now, perhaps some of us greet their annual arrival with a muttered humbug. After all, we can recite the story by heart these days. Why do we really need to hear it again?

Yes. Yes we do. But before I say why, let’s do a quick rundown of Christmas pasts.

Since Charles Dickens first penned A Christmas Carol back when the U.S.A. had just 26 states, we’ve seen the story visited and revisited many, many times. Back in 2016, the website justjaredjr.com counted a whopping 135 versions or revisions of A Christmas Carol between stage, screen and audio readings (including one Radio Theatre adaptation by Focus on the Family). And that was in 2016! Given that A Christmas Carol adaptations seem to multiply like holiday rabbits, that number’s surely larger by now.

And here’s another Scrooge-y fun fact: The first movie based on A Christmas Carol is thought to be 1901’s Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost—featuring cutting-edge special effects (for the time).

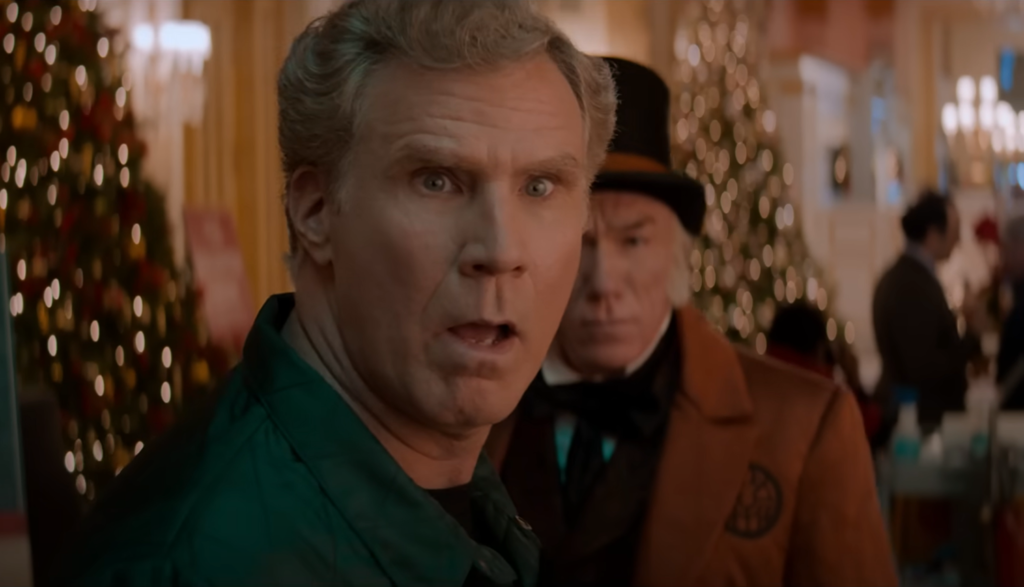

In fact, the most recent revision was released just a few days ago. While Apple TV+’s musical comedy Spirited doesn’t rehash Dickens’ original yarn, the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come are all well-represented, as is a rather dapper Jacob Marley.

Let’s be honest: Not much entertainment from 1843 has survived long enough to find a home in today’s pop-culture miasma. My guess is not many of you have read the bestsellers of the day: Catherine Gore’s The Banker’s Wife or James Fenimore Cooper’s Le Mouchoir; An Autobiographical Romance. Even Dickens’ own Martin Chuzzlewit—a 19th-century smash—doesn’t have a lot of 21st-century fans. So why has A Christmas Carol been so enduring? Why is it arguably more popular today than it was back in its own day?

We could point to lots of reasons, of course: The Victorian setting, the memorable main character, the ever-quotable dialogue. But I think it goes beyond that into something deeper. Something even vaguely theological. The idea of change.

We all know that at the beginning of the story, Scrooge is a big jerk. But Dickens reminds us that jerks are people, too. We see how he grew into his sourpuss self—a creation both of circumstance and his own poor decision-making. He wasn’t born to say Bah. He was made, and made himself, into who he became. The ghost of Marley tells him has much when he first shows up in Scrooge’s presence, pointing to his own chain as an illustration.

“I wear the chain I forged in life,” replied the Ghost. “I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it. Is its pattern strange to you?”

And that’s the way it is with us, too. Our choices and actions define who we are. Certainly, we’re not saved by our good deeds—but they are evidence of the Savior in us. As Paul writes, “And let us not grow weary of doing good, for in due season we will reap, if we do not give up (Galatians 6:9).”

We’ve all forged our share of chain links as well. The Bible reminds us, often, that we’re not so different from Scrooge. We “bah” the things we should praise, shout “humbug” to the things we should hold dear. We all fall short of who we should be. And I think if we could see our own chains, we might be surprised at how long and strong they are.

But just as Scrooge changed, day by day, into the person he became, change is possible the other way, too.

That’s the core message of A Christmas Carol—and of Christianity, too. We can change. We can be salvaged. We don’t have to be left in the pit. We don’t need to sit in the dark as Scrooge did. We can step out into the light—into the glorious, gleaming hope that Christmas is all about.

“I am not the man I was,” Scrooge tells the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come as he cowers by his own gravestone. “Why show me this, if I am past all hope? … I will honor Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. Oh, tell me that I may sponge away the writing on this stone!”

And it’s true of us, too: None of us are past hope. All of us can sponge away the writing—the shameful ledgers that we’ve written—if we but change. And that change, all change, begins with Jesus.

Spirited, for all its faults, powerfully and poignantly drives home the importance, and the possibility, of change. And it reminds us that change—real change—isn’t the product of one night’s decision. It’s about recommitting yourself to moving in a different, better direction day after day.

And while the film doesn’t take the next step, we Christians know what that commitment entails. It’s about forging new chains—golden, gossamer ones that link us to our Creator and our Savior, that bind us ever closer to him. Yes, we’ve seen A Christmas Carol—many, many versions of A Christmas Carol—more times than any of us can count. But its message is timeless. And it’s one that perhaps we can, and should, be reminded of: We’re all sinners. We can all change. And thanks to the miracle of Christmas, it’s never, ever too late.

Recent Comments