Good Times

Netflix takes a classic sitcom, Good Times, and turns it into a vulgar, violent, sexually-charged TV-MA show.

“Everyone is very happy.”

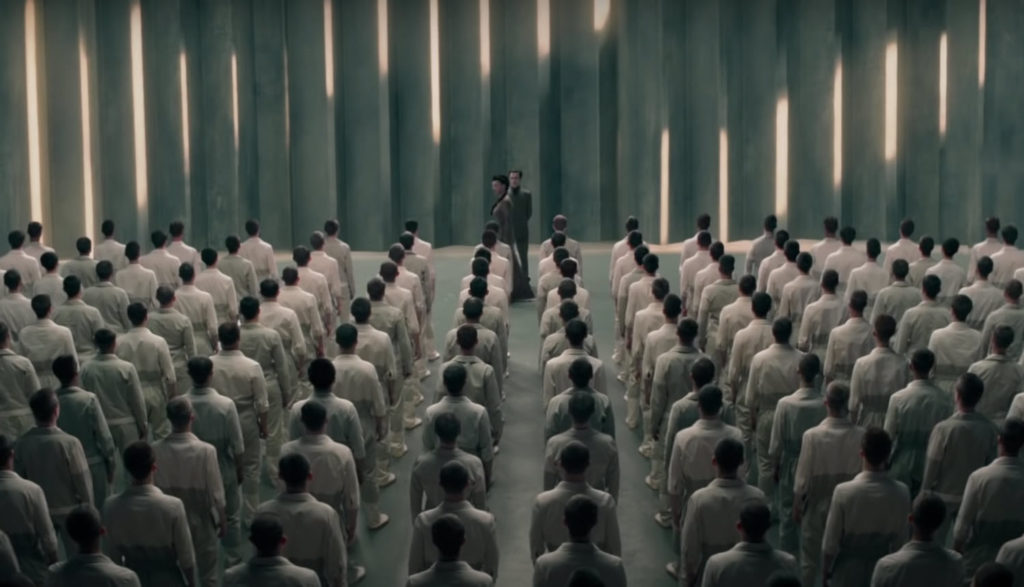

So we’re told at the beginning of Brave New World, the Peacock streaming service’s first flagship program. And so, at first glance, it would seem.

New London is indeed a place where everyone seems to sport a look of serene detachment, taking in the beauty and wonder of this technological paradise with a self-satisfied smile. No one has any family problems, because there are no families. Rather, people are hatched, as it were—genetically programmed to fit in one of New London’s strict social orders and like it, by gum.

Job dissatisfaction is a thing of the past, since everyone’s biologically wired and mentally conditioned to enjoy their jobs. Sex is still a thing, but monogamy is not: People are encouraged to jump from partner to partner without a thought. To do otherwise is selfish and retrograde, and any lingering attachment is quickly snuffed out as a threat to the social order. “Everyone belongs to everyone else,” goes the mantra.

And privacy? Why, that’s practically a myth in our own timeline. It’s certainly not better in this one.

If anything does happen to upend one’s emotional equilibrium, one can always take drugs. High-caste Alpha Bernard Marx will be happy to dole them out, like candy, to anyone who seems even the least out of sorts.

But if everyone’s so happy, Bernard wonders, why did a utopian worker just jump off a balcony and kill himself?

Truth is, it’s not like Bernard is all that happy himself. He occasionally disengages from the civilization’s always-on network (a very big no-no, especially for someone of his lofty caste). He occasionally even cries. Deep down, he understands there’s something off about this society, something wrong. “It’s not real,” he tells Lenina Crowne, a Beta-plus scientist, forbidden confidante and prospective lover.

Bernard’s superiors have noticed that Bernard’s been acting a little different lately, and they figure that all the guy needs is a little vacation—at an American-based theme park called Savage Lands. There, for visitors’ entertainment, real-life natives engage in all the activity that New London’s society got rid of long ago: barbaric surgical procedures. Black Friday shopping crushes. Even (gasp) marriage.

But some of those North American savages—even a few who work in the theme park itself—are tired of being rounded into reservations and gawked at. And John—a park prop worker living with his fragile mother and bearing a complicated history—may be the catalyst that upends both of these brave new worlds.

Aldous Huxley published the book Brave New World in 1932. Alongside George Orwell’s 1984, Huxley’s story marked the standard by which all dystopian novels are judged. He was taking satirical aim at his own age’s infatuation with technology, psychoanalysis, mindless consumerism and sexual superficiality. In Huxley’s book, Henry Ford and his efficiently faceless assembly line form the philosophical cornerstone of New London, with Ford himself transplanting more traditional Messiahs. Instead of saying “Our Lord,” residents would sometimes say, “Our Ford.”

Many of Huxley’s themes, carried over and adapted by this Peacock-based show, hit uncomfortably close to home. New London’s loss of privacy and legion of vacuous pleasures feel, perhaps, eerily prescient about what we see today. And yet, even as the show critiques New London’s superficiality (and thus satirizes our culture’s own), it embraces the very things it shames. It’s an irony that Huxley himself might have appreciated.

In some significant ways, Peacock’s Brave New World talks Plugged In’s language. As segments of our society push to separate sex from commitment, this show suggests sex for sex’s sake is empty and meaningless. As so many try to iron out all of our emotional wrinkles via chemistry, this reminds us that emotions, even uncomfortable ones, shouldn’t be obliterated. Indeed, they’re important to a life well lived. Metaphorically, New London is a place of cake with not a sliver of broccoli to be found. And it shows that at least some of its people are starving on their diet of frosting.

But here’s the paradox: When you make a TV show about a vacuous society that is (to borrow from educator Neil Postman) amusing itself to death, that TV show still must amuse its audience: It needs to be more cake than broccoli—and slathered, of course, with decadent frosting.

So even as Brave New World critiques New London’s cavalier attitudes toward sex, it dollops on a lot of sexual scenes—to the point where it often feels like pornography. It critiques New London’s no-privacy policy, but it strips its actors and extras bare before the camera, forcing them to perform for our entertainment. Inverse’s Eric Francisco wrote that the show “has enough sex and nudity to make Game of Thrones look modest.”

And that’s just the tip of the frosted iceberg. The show does not shy away from violence and gore. Nor does it censor harsh language. Marriage may be extinct in this utopian dystopia, but certain characters are still married to their f-words.

Huxley’s book was, in part, a satire of society numbing itself with vacuity, be it through sex or drugs or entertainment. It’d be hard to translate that book fairly to television—a medium built on the very society-sating entertainment he critiques.

If Huxley was still alive, he might write a book about it.

Scientist Lenina Crowne is called on the carpet by Bernard Marx, one of New London’s mid-level leaders, for failing to have sex with enough people—shaming her for having sex with just one person at least 22 times in the last couple of months. Lenina promises to do better. But Bernard (who also has an aversion to casual sex) is beginning to have doubts about how wonderful this utopia truly is. And when he’s called on to deal with the death of a worker—who (the official story goes) fell off a balcony—Bernard wonders whether he, instead, jumped.

Bernard touches the forehead of the dead man and has what he calls a “vision” of the man jumping and falling. “What if I said there was a kind of pain that soma (the drug that Bernard dispenses to rattled citizens) doesn’t touch?” he wonders.

Everyone in New London is connected to an always-on technological network, and no act is private. When Lenina tries to deny her two-month spate of monogamy, Bernard replays a number of sexual acts she had with the same partner: We see plenty of sexual positions and movements, along with some skin, but nothing critical is shown.

The same cannot be said for a later dance-fest/orgy, wherein hundreds of revelers strip their clothes off while sultrily dancing and eventually writhe on the floor, engaged in various sexual acts. (We see dozens of naked revelers on screen, exposing breasts and buttocks, and see them in a variety of sexual positions.) Even when the partygoers have clothes on (before and after), those garments are often see-through or barely there, revealing nipples and a whole lot of skin. Bernard, who’s in attendance at the nightclub, is approached by both a man and a woman (at the same time), the man stroking Bernard’s chest as the woman tries to undo his pants. Bernard makes his escape, though, before things get too intimate. (We see other intimations of same-sex unions, as well.)

We see naked people (including bare breasts and backsides) in 2D and holographic advertisements, too, including a pool-based orgy marketing Savage Land, a place where visitors can see all the “barbaric” acts that New London did away with. The ad includes a wedding before a pope-like figure (and Jesus paintings in the background), trumpeting these banished acts as “superstition.” (The ad also depicts an attraction called the “House of Monogamy.”) Savage Land also offers a dirty surgical room as an attraction, complete with blood, patients and corpses. (Those corpses and patients are presumably not really dead or in danger: Savage Lands is staffed by local “actors” who are engaged in a form of minstrelsy, exaggerating and reinforcing stereotypes for paying customers.)

John, a resident in the reservation-like region in which the theme park is set (and a prop worker at the park itself), helps a woman out of her pregnant bride costume, complete with fake baby bump. (The woman wears a thong bikini underneath.) He comes home and finds her mother lounging in front of a window in negligee. In a shop that John visits, we see a ceramic figure of two animals having sex, while a customer argues with the proprietor over what we assume is a similar statuette of a goat. (The proprietor says the statues are “totemic artifacts,” and he can’t separate the set just because of one man’s predilections.)

The very real corpse Bernard investigates has had his skull smashed. We see lots of gory wounds on his face, and the body is surrounded by blood. A coworker later seems to consider killing himself, too; he takes a makeshift razor from underneath a bed and stares at it solemnly. Someone is pushed over and conked in the head with a gun. People are threatened. Someone sits on a toilet with his pants down.

Plenty of people in New London take mood-enhancing pills of various shades, with Bernard distributing them generously to most anyone who asks. In the savage lands, John and his mother drink some sort of liquor at dinner, and John drinks beer on a couple of occasions.

Characters say the f-word seven times and the s-word four times. We also hear “a–,” “h—” and crude references to the male anatomy. God’s name is misused twice (once with the word “d–n”), and Jesus’ name is also abused twice. Someone makes an obscene gesture.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.

Netflix takes a classic sitcom, Good Times, and turns it into a vulgar, violent, sexually-charged TV-MA show.

While its protagonist might live a nuanced life, The Sympathizer’s problematic content can’t be described the same way.

Say hola once again to the iconic explorer in this faithful reboot of the children’s series.

Based on a popular video game, Ark: The Animated Series features hungry dinosaurs, bloodthirsty people and plenty of problems.