Based on a heretical gnostic gospel, The Carpenter’s Son depicts a teenager grappling with his apparent divinity and an earthly father who doesn’t think the boy’s doing a very good job. Classified as a horror film, this movie is indeed horrific—both in body and soul.

Ever since the Boy was born, the Carpenter and his wife have been on the run. From town to town, village to village, always seemingly a step ahead of the Romans. Or angry villagers. Or worse.

But here, in this nameless hamlet, perhaps they can rest for a bit. They could sure use it.

The Carpenter can find a little work here—though his biggest contract is to carve an Egyptian idol, and that’s not great, all things considered. Still, it’ll pay the bills. It’ll keep them safe. And the Boy is nearly grown now. Nearly ready to take on the great mantel he was born for.

If the Boy is who the Carpenter has tried to believe he is. These days, the Carpenter is not so sure.

The Carpenter and the Mother have, thus far, taken great pains to keep the Boy’s true identity a secret—even from the Boy himself. Maybe if the kid knew, he’d start taking his responsibilities a little more seriously. But still, the Carpenter would’ve hoped by now that the Boy would start growing into his world-saving role. But honestly, the Boy doesn’t always seem like Messiah-like material to the Carpenter. He doesn’t listen like he should. Pray like he should.

“Each year I walk beside him and see only the tarnished image of man,” the Carpenter prays. “Tell me from whence did he come? Is he from Your angels? Or from demons? Is he Your Son?”

Give him time, the Mother cautions. But time is running out. The Carpenter tries to make the Boy do better—but lately, the Boy’s been pushing back.

And he’s not the only one pushing. The village seems to be home to some sinister forces—forces seeking to harm the Boy, or worse yet, corrupt him. The Carpenter will do whatever he can to prevent that from happening. But it won’t be easy. Especially if the Boy himself might want to be corrupted.

So if The Carpenter’s Son was really just about a carpenter and his son (albeit a son with some supernatural abilities), we could talk about the Boy’s sense of confused goodness. He’s not exactly sure who he is or who he should be. But he still heals a wound. He ejects a demon. He clearly loves his mom. And all that’s just dandy.

The Boy has a complicated relationship with his apparent father, though—and we can see something worth talking about in that tension, too. Again, if we’re just thinking about father and son as a regular ol’ father and son, their relational dynamic would feel familiar in many a family: The father doing his best to teach his boy the right way to do things but not sure how. The son wanting to please his father but failing more often than not. Eventually, they come to understand and appreciate each other a little more.

But …

The Carpenter’s Son claims to be based on the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, a gnostic text supposedly documenting Jesus’ childhood up to and including his visit to the Temple at age 12. It’s been considered heretical pretty much ever since it was first written. But even so, the film wildly departs from its source material—making it, I suppose, a heresy of a heresy.

The Boy (who is supposed to be Jesus Christ) looks like he’s in his mid-to-late teens, which places him at an age well past the age when Jesus knew who His real Father was. (See Luke 2:41-52.) But here, the Boy initially believes that the Carpenter is his biological father—a belief that his Mother tries to preserve by lying to the Boy. And while the Bible tells us that Jesus was without sin, the Boy takes some sinful missteps here. He disrespects his earthly father. He sneaks out. He apparently eyes a woman with lust in his heart—which the real Jesus tells is an issue (Matthew 5:28).

The Boy doesn’t do any of this in a vacuum. He receives several pushes from someone who appears to be a girl perhaps a few years younger than he. The credits call her “The Stranger,” and she tricks him into touching a leper (a forbidden act, given that lepers were considered unclean). She gives him a wooden snake (no symbolism there) and tells him to keep it a secret. “To do things in secret is a greater pleasure,” she whispers.

“What is it to say that man is wicked?” she asks the Boy. “It only means that you have given up trying to understand it.”

The Stranger, of course, eventually says that she’s Satan incarnate. And she—not God, nor the Boy’s parents—reveals to the Boy the fullness of his divinity. She tells the Boy a bit of her own story, too. “I was a very beautiful thing,” she tells the Boy, but God kicked her out because He would “let no one be His equal.” She admits, though, that God gave her a home—a red, writhing place filled with screaming half-man, half-slug creatures. “There is a purity in that place,” she insists to the Boy. “Order. Now that you are with me, we will go together.”

Another word about Satan here: She’s still under the dominion of God in some respects, as she admits that she was sent (presumably by God) to torment the Boy. But the movie also turns her into a pathetic, hurting creature. She’s often covered with cuts that feel more like self-harm than injuries she received in conflict. She carries herself as a victim denied of love. And while she’s unquestionably evil (and called so to her face), she presents the evil acts she commits as sadistic mercies. “This place is a cage,” she says of the earth, and she has “freed many souls from this awful place.”

We see the Carpenter, the Boy and the Mother all pray—often fervently. The Carpenter instructs the Boy to offer formal prayers straight from Scripture. (For instance, the boy is forced to repeat Psalm 91:2 to God: “You are my refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.”) The Carpenter uses other spiritual techniques to protect his family, too. When the Boy offers him bread, he refuses it, saying that he’s fasting. “In emptiness you find the strength to bear against Satan,” the Carpenter says. He spreads dirt or ash across the threshold of his house, too: He tells the Boy that if an evil spirit walks in, he’ll know because it’ll leave rooster tracks. (He indeed sees a set of rooster tracks at one point.)

But that doesn’t keep the Carpenter from carving a huge idol of the Egyptian god Bes for a client. The commission goes awry, however, when the Boy recites Scripture and the idol falls to the ground, breaking it. (Earlier on, the movie offers a bit of foreshadowing, with the Carpenter saying the Boy was meant to “threaten” the world’s gods: “And he does so threaten them.”)

For a time, the Boy is taught by the local rabbi. And when the rabbi scolds the Boy for not knowing Scripture well enough, the Boy says, “I know more than how to speak these words,” and he apparently tells the rabbi how long the man has to live. (The rabbi refuses to teach him any longer after that.) Other townspeople call him “Belial” (another name for Satan) and a conjurer, and even the Carpenter accuses of the Boy of engaging in black magic.

We see a demon-possessed woman, and the demon is later exorcised by the Boy. We hear references to dreams and visions, and the Boy seems to have premonitions of his own death. The Carpenter tries to lay a guilt trip on the Boy, telling the teen that without him, the Boy would “be a beggar in hiding, asking for alms from sickly priests who feed their sacred crocodiles and mumble to their idols.”

When the Boy is asked what awaits us after death, he says, “dust,” an opinion that seems to countermand the Stranger’s own description of hell. An outdoor prison holds people “accused of sorcery” and “conjurers of evil deeds.” The Boy crushes, then resurrects, a grasshopper. The Carpenter forces the Boy to recite all the things that one should not do on the Sabbath.

The film depicts demons as snakes—and when someone’s possessed, those snakes literally live inside their victims. We see necks and abdomens stretch and pulse with the vile things. And when the Boy exorcises demons, he pulls the snakes grotesquely out of human mouths.

The Boy seems to be attracted to a neighbor named Lilith. He spies on her as she bathes and pours water over her naked body (which we see from the side). When the Boy hears someone coming, he quickly and guiltily puts a shutter on the window.

The Carpenter begins to doubt that the Boy is the Son of God, and he wonders whether the Mother conceived him by other means. “And what then, if none of it were true?” the Carpenter says in the movie’s stilted dialogue. “That I have been living with an unclean woman all this time?” He speculates that the Boy may be the “son of a Roman.”

A woman wears a shoulder-baring outfit.

The Carpenter’s Son is classified as a horror movie, and we do indeed see plenty of horrors.

The story actually begins with the Carpenter and the Mother’s flight to Egypt with their newborn son. They go past a pyre being fed with live babies—ripped from the arms of screaming mothers and tossed into the flames. (We see a closeup of one such baby burn.)

A possessed woman bites into the face of someone else, ripping off the flesh and clutching it in her teeth. (We see the gaping wound as well.) The Stranger lures the Boy to a sort of outdoor prison: People are chained, tortured and executed here—by crucifixion, naturally. We see the dead and dying hanging from crosses, their wrists and feet pierced by nails; blood dribbles from at least one person’s mouth. Others are chained to rocks, various wounds bleeding. Corpses lie unattended.

A character brutally snaps someone’s wrist. Someone is stabbed in the gut with a huge tree branch and dies. Another person is killed by eating a poisoned peach. (The dead man’s swollen tongue juts out of his mouth.) A woman is pulled, screaming, from her home. Two people fight; one of them nearly dies after the other pushes his face into the mud, trying to suffocate or drown him. Lepers exhibit terrible-looking wounds. People sometimes march around like zombies.

The Boy has dreams of his own death: on the cross and in a burial shroud. He’s at first terrified of these dreams, and the Carpenter kicks him out of the house for his fear. (“You can sleep in the house when you stop screaming!” he shouts.)

The Boy kills someone with a thought. The Carpenter hurts himself, drawing blood. A snake bites a man’s calf. Someone punches the Mother in the face. A person is beaten into submission. The Stranger asks someone to kill. Wounds mysteriously appear on a character’s skin. The Stranger is often covered with either fresh or still-healing cuts.

When a character is about to be killed, another successfully asks the would-be killer to show mercy.

One use—albeit a correct one—of the word “b–tard.”

None.

Several people lie. We see the Mother giving birth and the Carpenter violently cutting the umbilical cord. Years later, The Carpenter casts the Boy out of his house, and his presence, for a time. “You follow no man, so be it!” the Carpenter says. “Go be a man alone.”

“Disgusting.”

“Utterly disrespectful.”

“Sick.”

So read some of the early Google audience reviews for The Carpenter’s Son, loosely based on an apocryphal story written almost 200 years after Jesus’ time. According to Google’s audience ratings summary, people hate this film: Most responders gave it a one-star rating. Never mind that most of these “reviewers” haven’t actually seen the film itself. Just the trailer.

I tend to hold such early reactions loosely: What we think we’ll see in a movie doesn’t always reflect the movie itself.

But sometimes it does. And in this case, a lot of those early reactions were right on the money.

If we stripped The Carpenter’s Son of all its religious underpinnings, the film would still be plenty problematic. This is R-rated horror, no asterisks needed. It’s bloody, grotesque and disturbing. Throw in some gratuitous nudity and you’ve already got plenty of reasons to skip this one.

But The Carpenter’s Son uses all of that R-rated content in the service of a story that is based on the Holy Family. The movie undermines Scripture and even twists and tortures its own heretical source material. Blasphemous? Oh, yes. The Carpenter’s Son meets that definition and goes well, well beyond.

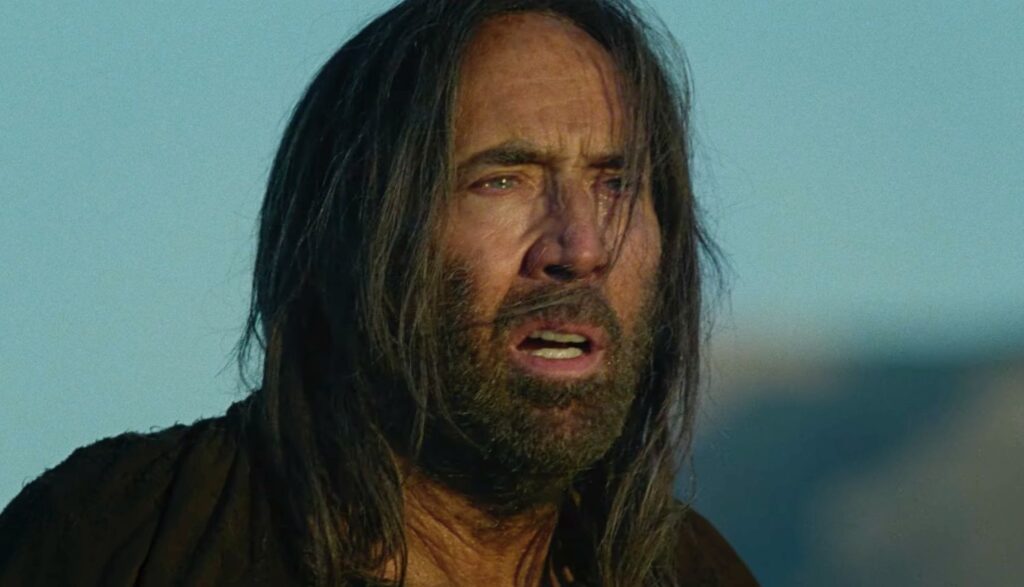

And even if you came into this movie as a straight-up atheist, you’d be disappointed, because aesthetically (and despite the presence of the always-committed Nicolas Cage), the film just isn’t very good.

We should give director Lotfy Nathan some credit. A Coptic Christian, Nathan is grappling with apparently sincere questions: Did Joseph ever have moments of doubt about Jesus’ divinity? When did Jesus understand His own nature? Just why is Satan so mean, anyway? To me, it would appear that Nathan is not seeking to belittle Christianity so much as he is seeking to understand it.

But to understand Christianity, one must understand Christ. And to understand Christ, one must go to the book—the real book—that tells us about His life, His nature and His teachings. There’s a reason why the Bible has been embraced and accepted for thousands of years as the revealed Word of God. There’s a reason why the Infancy Gospel of Thomas isn’t included in it—and why it was deemed heretical practically from the moment its ink dried.

Yes, Christianity is steeped in mysteries. I’m sure that many devout Christians have plenty of questions about our faith and our Savior. But we have the most important answer: We know where our hope resides. And that hope looks nothing like The Carpenter’s Son.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.