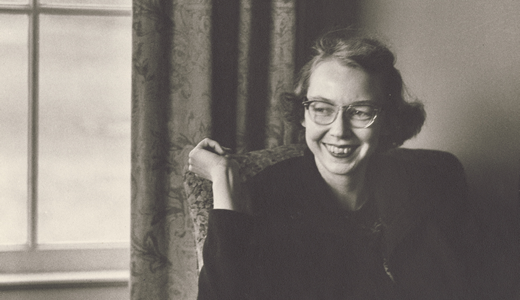

When she was attending the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the mid-1940s, Flannery O’Connor asked her priest whether she could write about “difficult things.” We can only assume that the priest gave O’Connor his blessing: Few writers have tackled more “difficult things” than O’Connor.

The new documentary Flannery, playing at a variety of “virtual cinemas” across the country beginning today, examines one of the most powerful, most paradoxical literary voices of the 20th century. It offers insight into the famous writer, exploring how her Catholic faith informed her challenging, troubling stories. And in a way, it helps illustrate the sometimes-difficult relationship between art and faith as well.

Say the words “Christian literature” or “Christian entertainment,” and likely it’ll stir up a whole bunch of images, even stereotypes, in your mind. Sunlight streaming through clouds. Melodramatic salvation stories. Inspirational football flicks. Touching Mennonite romances. Redemption. Salvation. Obviously I’m generalizing, but my knee-jerk reaction to what we broadly define as Christian art is that it’s almost always something that, when you’re done reading or watching or listening to, makes you feel better about stuff—God, yourself, everything.

O’Connor’s work is not that. In fact, when I read her stories, I often feel worse. She writes about sex and violence and death and “freaks.” Often her most loathsome characters are the most religious ones. Her first novel, Wise Blood, stars an atheist street preacher (promoting the “Holy Church of Christ Without Christ”) and was labeled, by some, as the work of a nihilist.

“You’d think that it’s a bitter old alcoholic who’s writing these really funny, dark stories,” comedian Conan O’Brien says in Flannery. “And then you find out that she’s a woman and she’s devoutly religious.”

Not everyone got the faith behind O’Connor’s troubling tales. Indeed, very few did at first. When a reader named Betty Hester wrote a letter to O’Connor, suggesting that all of her stories were ultimately about God, O’Connor embraced the reader like an old friend. She later wrote to Hester:

One of the awful things about writing when you are a Christian is that for you the ultimate reality is the Incarnation, the present reality is the Incarnation, and nobody believes in the Incarnation; that is, nobody in your audience. My audience are the people who think God is dead. At least these are the people I am conscious of writing for.

The documentary Flannery unpacks O’Connor’s life from beginning to untimely end (she died at the age of 39). It talks about her comfortable childhood; her fledgling aspirations of cartooning; her time at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop; and her sojourn to Yaddo, a famous artists’ and writers’ community in upstate New York. It unpacks her battle against lupus (which for years she was told was just arthritis), the disease that ultimately sent her back home and claimed her life. In 1951, she returned to the family dairy farm near Milledgeville, Georgia, where she spent the last 13 years of her life with her mother, the cows and some 40 or so peacocks.

The documentary talks about her faith, too. Which for a Christian critic like me, is both the most compelling and challenging part of her story.

When asked to explain what Plugged In does and why it does it, I sometimes point to Philippians 4:8: “Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things.”

At Plugged In, we call out the things that are true and honorable and just and pure in our movie reviews—and we point out those things that aren’t, so you and your family can decide whether or not to avoid a particular movie (or television show or video game), or whether it’s something you might be able to use as a springboard to deeper dialogue.

But I think that all of us also realize that some worthwhile stories—even some worthwhile Christian stories—may not always feel very pure or lovely or just: no alter call, no sunlight streaming through clouds. O’Connor’s stories fall in the latter category, and they’re filled with the false, the unjust, the grimy, the ugly.

And yet through them, perhaps, we can paradoxically see the beauty beyond.

In the story Wise Blood, O’Connor’s hero, the atheist preacher, eventually blinds himself. The story (it would seem) ends on a bleak, grotesque and oddly ambiguous note. But as actor Tommy Lee Jones notes in Flannery, the story was really about the protagonist running away from, and being hounded by, God. What’s left unsaid is that perhaps the man found Him in the end.

When atheist director John Huston turned Wise Blood into a 1979 movie, he allegedly said near the end of filming that he’d been “hoodwinked.” According to Flannery, he thought he was telling the story he wanted to tell. Instead, he eventually told O’Connor’s story—filled with an undercurrent of spirituality that he’d been unaware of until filming was almost done.

“Jesus wins,” Huston allegedly said.

That’s what O’Connor believed, and that’s what her stories ultimately tell us, according to Flannery—even if that ultimate truth, like God Himself, isn’t always so obvious.

Recent Comments