Knuckles

The Sonic spinoff blends explosive adventure and road-trip-buddy-comedy into a fun romp for both kids and diehard fans.

When Netflix released its South Korean drama Squid Game two years ago, it became one of the streamer’s biggest hits ever. It depicted a game show, but with a few twists you’d not find in The Price is Right or The Amazing Race.

First, the game show at the center of Squid Game was never meant to be a worldwide hit: Its audience consisted of a handful of very rich, very sadistic viewers.

And that brings us to the second twist: The winner would earn millions of dollars, to be sure. But the hundreds who lost? They wouldn’t leave with handsome parting gifts. In fact, they wouldn’t leave at all.

Now, doesn’t that sound like a game we’d like to watch in real life?

Well, Netflix sure thinks we think it does.

Admittedly, no one dies here (though several contestants did seek out some medical attention, according to reports). And Netflix is indeed hoping for millions to watch, not just a moneyed few. But this is not an exercise in straight-up voyeuristic murder.

But Netflix does its best.

The games from the fictional show—Red Light, Green Light; Cookies; Tug of War—are conscientiously replicated here, complete with the creepy singing doll in Red Light, Green Light and the hard-to-carve shapes in Cookies. The sets look freakishly similar, down to the faceless guards and pastel M.C. Escher staircases. And instead of people literally being killed for their troubles, the game tries to replicate fatalities by exploding little paint packets on their chests. (The paint is black, not red.) Many contestants fall down when their packets explode, dutifully “dying” for the cameras.

But fatalities or not, the real sadism is baked straight into the game already.

The purpose behind the original Squid Game wasn’t just to titillate audiences with a lot of blood and guts and death (though it did that, too). It was a critique of capitalism and, deeper still, the human psyche: What would you do to earn enough money to save your family? Would you die? Would you kill? The game’s original 456 contestants were willing to do both.

Obviously, the 456 contestants in Squid Game: The Challenge will, win or lose, be leaving the set via their own power, not by body bag. They’re not out to actually kill anybody.

And yet, you get the feeling that some of these contestants might consider it.

One contestant cheats his way to extra food in the opening episode. “At the end of the day, we’re not here to play fair,” he says. Another player says, “To me, everybody is just money,” referencing how the prize increases with each “death.”

An added wrinkle to The Challenge has to do with some in-between-game “contests,” designed to weigh the morality of contestants. Participants are given the chance either to give someone a little extra help in an upcoming game, or they can—anonymously—choose a contestant to eliminate. First time up, two contestants (who seem nice enough) immediately leaped at anonymous elimination, wiping one of the most popular contestants from the game.

“How you play is who you are,” the game’s representatives intone, and there’s truth in that. If we were going to be generous, we’d say that this game exposes how bad we can often be—and how much we need help. How much we need saving.

But we can’t give this show too much credit.

The original Squid Game was designed to critique society, to examine the human soul and ultimately to judge those who would seek to exploit it. But this real-world take on the show is the exploiter. Viewers of the original Squid Game were supposed to be sickened by this game show. Viewers of The Challenge are supposed to be entertained. Writing for The Hollywood Reporter, Angie Han says, “The Challenge builds on the most superficial aspects of Squid Game while ditching — or, really, undermining — the most profound [aspects].”

The show has plenty of other issues, too, including swearing and a few LGBT and trans characters.

The good news regarding Squid Game: The Challenge”? No one died making the thing. The bad news? It feels like maybe a little bit of my soul did by watching it.

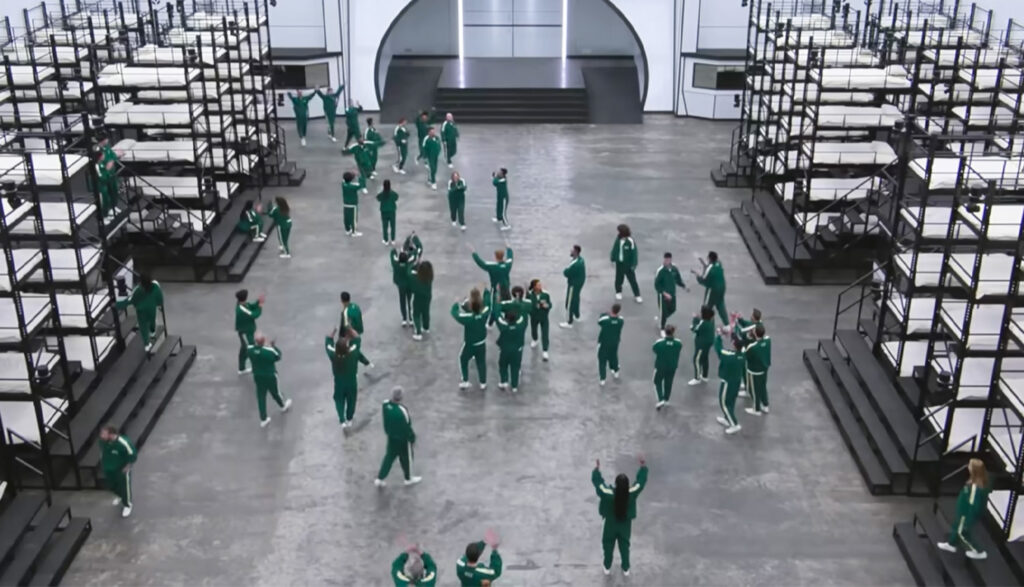

Contestants, 456 of them, gather to begin the “game” (really a series of several games and contests) with a chance to win up to $4.56 million. The games themselves begin with Squid Game’s iconic Red Light, Green Light competition: Competitors must cross the finish line in five minutes, all while a gigantic doll sings. But the catch is that when the doll stops singing and turns around to face the contestants, anyone who’s seen to move is “killed.”

We know who dies because black ink packets explode around their neck/chest area, indicating they’ve been shot (as happens in the original Squid Game). By the time the game ends, the contestant roster is whittled down to fewer than 200. All the “survivors” sleep in the same massive dorm, where some might argue the real game begins.

We hear from several contestants, some of whom seem to be pretty likeable. Trey is competing with his mother, Leann. “I did this because of her,” he says. “I wanted us to have an experience.” Another contestant, Rick, celebrates his 69th birthday in the dorm, and when the other contestants sing “Happy Birthday” to him, he enthuses that it’s the best birthday ever.

Others are not so likeable. One contestant, Bryton, declares that “sympathy is a weakness,” then seasons it with, “Jesus had to compete, so I have to compete,” he says. Later, he admits, “It’s almost selfish, because I love myself so much. I know who I am. I know God made me this way.”

When it’s dinner time, one contestant (Lorenzo) stands in line for his portion—then hides his dinner and goes back to collect another. During an interview, apparently conducted before the competition began, we see him in what appears to be a summer hat and a dress. He encourages people in his interview to “break free from everything, every moral. … Do what you want.”

A couple of contestants kick somebody out of the game, then pretend they knew nothing about it. Several people act selfishly and duplicitously. There’s a reference to LSD (referred to as “acid” here).

Characters say the s-word five times. We also hear “a–,” “d–n,” “crap” and “h—,” And we hear God’s name misused around 25 times. Jesus’ name is abused once.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.

The Sonic spinoff blends explosive adventure and road-trip-buddy-comedy into a fun romp for both kids and diehard fans.

Dead Boy Detectives targets teens in style and story. But it comes with very adult, problematic content.

An elf mage contemplates on connection and regret as she watches her human friends grow old and pass away.