[Editor’s Note: This review is for both the original R-rated Father Stu and for its PG-13 re-release, Father Stu: Reborn. Both movies are largely the same, with the exception of the amount of crude and profane language. Additional content information in that section is italicized.]

Stuart Long didn’t go to the City of Angels to find God. He was looking for salvation of another kind: the kind you fold up and put in your wallet, the kind you see on movie marquees. Fortune and glory, friend. Fortune and glory.

God? Yeah, God was for losers. And Stu, he wasn’t no loser.

Stu had a pretty good run as an amateur boxer, winning more than he lost. And even when he did lose, the guy in the other corner sure knew Stu packed a wallop. But the Montana fighter was getting older now. And after every bout lately, he’d come down with these weird infections. “It seems like your body’s telling you not to fight,” his doctor said.

Stu needed a new career. Why not acting? Why not use that pretty face of his for something more than a punching bag?

‘Course, no actor makes it big without some struggles. So Stu took a job at a supermarket meat counter to pay the bills ’til someone saw his raw talent.

He didn’t see God there as he stood behind the counter: just a pretty woman. But Stu was smitten with her from the very first, as if Bathsheba herself walked into the grocery store.

“I’d wait 40 years in the desert for you,” he soon tells the woman, Carmen.

“Start with an hour in church,” Carmen says. See, she’s Catholic—deeply so. And she’s not about to go out with some roustabout who doesn’t love God just as much as she does.

So, Stu starts going to church. Then Stu gets himself baptized, too. A little holy water can’t hurt, right?

And then one night, after drinking a little too much, he runs into God.

Well, actually, he runs into a car. His motorcycle smashes straight into one, and Stu goes flying, rolling, bleeding. The police find him lying on the asphalt—body crushed, barely breathing. Most everyone thinks he’s going to die.

But he lives.

And Stu remembers, before he climbed aboard that bike, he met someone. He mistook the guy as just a wandering barfly, but one who talked with a level of sincerity unusual for the time and place.

“Life’s gonna give you a gut full of reasons to be angry,” the guy told him. “You only need one to be grateful.”

Stu’s grateful he’s alive. He’s grateful for this second chance. Maybe God is for losers. Stu’s ready to admit that he’s a loser, too.

And he’ll lose a lot more before it’s done.

Father Stu illustrates how change often manifests in our lives: It begins with sometimes the smallest beginnings—a pebble chucked in a pool of water. But the ripples can radiate in ways we’d never expect.

The Stu who comes to L.A. is shallow and selfish and very, very lost. His turn toward religion is, initially, selfish and shallow, too. But with Carmen’s patience and guidance, something takes root, even though Stu himself is barely aware of it. So when the big catalyst comes, Stu’s ready to swing in an entirely new, and wildly positive, direction.

Stu’s parents are equally lost. His mom, Kathleen, and dad, Bill, split up long ago. Bill and Stu barely speak to each other, and when they do, their conversations are full of rage and bitterness. When Stu moves toward religion, both Kathleen and Bill are, honestly, kind of horrified.

But as Stu’s story moves forward, his mom and dad begin to see its beauty and, more importantly, changes in their boy. Kathleen and Bill draw closer to Stu and, apparently, closer to each other, too. Stu’s turn to God becomes a catalyst for healing. And while we don’t know if Kathleen and Bill eventually come to embrace Christianity as much as Stu does, we can see Christ’s “living water” lap at the edges of what had been a dusty, dry shore.

If a Christian movie can have scads of profanity in it, well, Father Stu would be, unquestionably, a Christian movie. Christ’s grace lies at the center of this story, and the narrative follows the template of the jaw-dropping testimonies that so many of us have heard in church. I can’t delve into every instance of religion and spirituality we see here, but I’ll try to give you the movie’s Christian, Catholic flavor.

The Stu we first meet isn’t just indifferent to Christianity. He’s hostile toward it, so much so that he drunkenly slugs a statue of Jesus in the face. (Blood stains the statue in a nice symbolic shot.)

But Carmen pulls him into the orbit of her Catholic parish. Soon he’s helping her teach Sunday school. Then he’s getting baptized, which opens the door to meeting Carmen’s family. (During dinner, Carmen’s father talks about how his family would crawl for miles on their hands and knees to the foot of the cross, and that he expects “no less devotion to my daughter.” “Well, it’s a good thing I’ve got a carpet,” Stu quips.)

We can see even then Stu puzzling through some of the mysteries of faith, trying to weigh how real it is. But it all comes to a point when he finds himself sitting next to a bearded man that Stu later believes might’ve been Jesus. This “Jesus” clearly suffered much (and swears on occasion). But He speaks with authority and knowledge, and the conversation sticks in Stu’s mind after the accident. When Stu crashes, he believes that the Virgin Mary kneeled beside him, too, as he lay bleeding and nearly dead on the asphalt. In the hospital, Carmen puts a Bible underneath his arm. Carmen gives Stu a St. Joseph medal, too.

As Stu recovers, his conviction in Christ grows, and he decides (much to Carmen’s chagrin) to become a priest. His mother and father are both incredulous: Bill compares it to “Hitler joining the [Jewish-centric Anti-Defamation League].” But he’s not swayed. Stu enters the seminary, determined to be a priest “who’s gonna fight for God,” and while some of his fellow acolytes are put off by his language and rough-hewn attitude, he persists.

Throughout Stu’s time in the seminary, he thinks and sometimes speaks on themes of grace and forgiveness. But while he’s still studying, Stu is stricken with inclusion body myositis—a disease that progressively and inexorably robs the body of the ability to move as it should (and is often compared to Lou Gehrig’s Disease).

The Catholic Church is at first unwilling to let Stu continue his priestly education, worried that an impaired priest won’t be able to perform the required functions. (An example might be spilling the holy communion wine during Mass.) We see Stu struggle mightily with his new affliction, too—tearfully praying before the cross as he wonders why God would do this to him. But his faith doesn’t waver even then.

Advocates for Stu’s ordination eventually break down the objections, and Stu is officially ordained. Back in Montana by that time, he moves into the Big Sky Care Center and ministers to people there.

We see Stu and others confess their sins in confessional booths. Bill sees a cross on Stu’s wall and snidely dismisses his new décor. Bible verses are quoted often. Stu asks questions as part of a confirmation class and debates with fellow acolytes as they study to become priests. Stu learns that one of his fellow students never wanted to be a priest but was pushed into the profession by his family.

Shortly after Stu and Carmen meet, Carmen tells him that he’s heading down the wrong road in terms of their relationship: She’s Catholic, and she won’t sleep with someone outside of marriage. “Isn’t that what confession’s for?” he asks.

Carmen later breaks that vow after Stu is nearly killed in his motorcycle accident. She begins to kiss him and climbs into his hospital bed, even as Stu protests. But while the camera cuts away, we learn that Stu gives in. Later, he admits in confession, “All I could think about is disappointing God.” (The priest tells him that’s progress; that being convicted by sin is the first step toward forgiveness and sanctity.) When Stu decides to become a priest, Carmen is quite upset, given its accompanying vow of celibacy.

Much earlier in the story, Stu auditions for a role. The producer asks Stu how much he wants the role, pushing his chair away from his desk and gesturing to his groin. Stu punches the man in the face, knocks down the audition camera and storms out.

We see Stu shirtless frequently, most often in the boxing ring. In one scene, he shadow boxes in nothing but his protective boxing undergarments. A flashback shows Stu at about age 11, dancing to Elvis in a just a shirt and underwear. In a bar, sitting next with “Jesus,” Stu makes a quip about the size of his anatomy. “Jesus” tells Stu that he already knows how large it is. When Stu’s diagnosed with inclusion body myositis, he’s told the last thing to go will be his body’s erectile functions—of little use to someone training to be a priest, Stu bitterly quips. A Sunday school student says that his dad gave up porn for Lent. Someone asks Stu if he’s going to a “porno.”

Stu’s motorcycle accident is jarring. His bike hits a car and Stu goes flying—only to be hit by another oncoming vehicle. His face and body are covered in blood, and he only looks a tiny bit better in the hospital.

Stu begins the movie as a boxer, and we see him in several fights. He punches people viciously. He has cuts patched mid-fight, and he spits blood-filled water into a bucket.

Stu finds his dad passed out on the floor of his trailer, holding a gun. It’s not known why Bill was holding the gun, though there is some talk of suicide. Stu fantasizes about punching one of his fellow presbyters.

We learn that Stu’s brother died as a child, which (the movie suggests) is one reason why the family is so fractured and hostile toward religion.

When Stu first begins to consider Catholicism more seriously, a priest suggests that he might want to start thinking curbing his tongue. And boy, could he and his family use a little tongue-curbing.

More than 40 f-words are uttered during the film, along with at least 45 s-words. We also hear plenty of other profanities, including “a–,” “b–ch,” “d–n,” “h—,” “pr–k,” “d–k,” “n–ger” and “p-ss.” God’s name is used with the word “d–n” five times (once during a tearful prayer in front of an altar), and Jesus’ name is abused twice.

In Father Stu: Reborn, the level of profane language has been edited down significantly. No f-words remain, and there’s just one solitary use of the s-word. We still hear some scattered profanities (“a–,” “b—ch,” “b—tard,” “crap,” “d—n,” “h—,” “p-ss” and four misuses of God’s and Jesus’s name), but not nearly in the numbers as in the original.

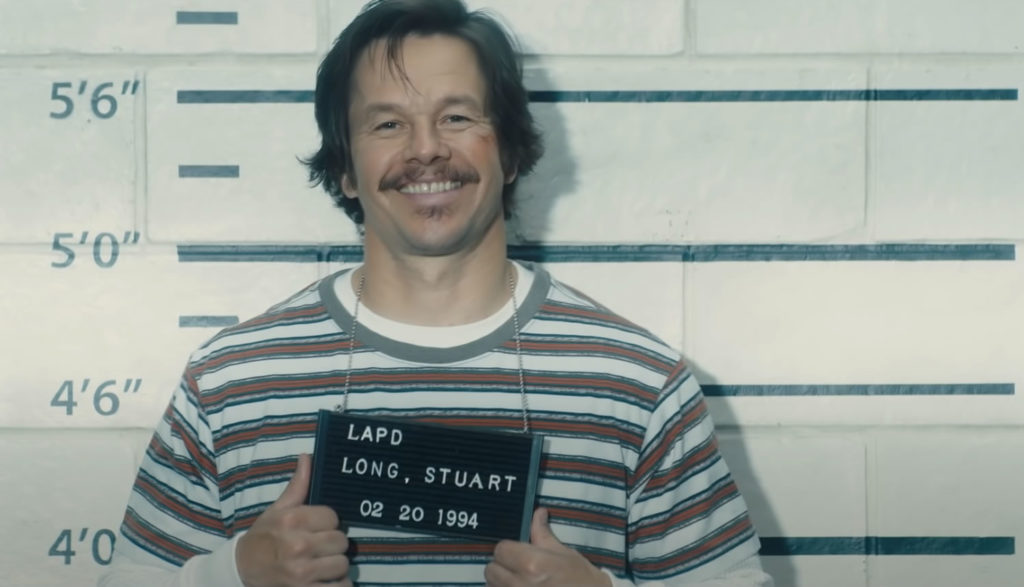

Stu drinks heavily before his turn toward the priesthood. He guzzles beer as he remembers his little brother at a church cemetery, and then throws bottles at (and punches) a statue of Jesus. (He’s arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct and mugs for the mugshot camera.) He’s inebriated when he crashes, too.

Bill also drinks heavily, and we see him passed out in his trailer more than once, with liquor bottles and glasses strewn about. Some characters smoke as well.

After Stu is diagnosed with his illness, we hear discussions about how he’ll perform certain bathroom-oriented bodily functions. After the disease progresses, we see him on the toilet. Afterward, he hikes up his underwear and tries to get off the toilet, but he falls. Bill has to break in and pick him up.

Father Stu is based on the true story of Stuart Long, a former boxer and actor who became a priest in 2007—and died in 2014 at the age of 50. For Mark Wahlberg, who stars and produced the film, the project was his most personal.

You can understand why. Like Stu, Wahlberg was a wild child: His past is filled with a record of assaults (some race related). Like Stu, he wanted to be a star, fronting the hip-hop group Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch. Back then, he was about as far away from being a religious role model as you could be. But as the musician-turned-actor grows older, Wahlberg seems to embrace the Catholicism he grew up in more and more.

“This is me kind of transitioning to doing more meaningful work that serves a purpose in my faith,” Wahlberg told the Deseret News of Father Stu. “Also, I’m getting older. I’ve been very blessed and fortunate, and so to do things, to utilize the talents and gifts that God has given me in this way is definitely what I’m supposed to be doing.”

Father Stu features a very imperfect Christian playing a very imperfect Christian. No surprise, perhaps, that the movie itself is both inspiring and imperfect, too.

Listen, faith—and how that faith manifests in us fallen sinners—is messy. We’re messy. Record just a single day with most of us, and the censors would slap it with a big ol’ R rating—if not boot it from the theaters completely.

But there’s a reason why bedrooms and bathrooms tend to have doors. And there’s perhaps a reason why we don’t invite movie cameras into those messy moments in our lives, either.

The PG-13 rerelease, Father Stu: Reborn, cleanses away some of the movie’s problems, particularly in the language department. Talking with Fox News, Wahlberg says that they cut out “200 and some-odd swears … and the film is just as powerful.” That may help draw in faith-minded viewers that had steered clear of the original because of its R-rating.

But while Reborn may be cleaner, it’s certainly not pristine. Stu’s motorcycle accident is still just as wince-worthy. His relationship with Carmen remains unchanged. The film still feels rough and earthy. And I get it. The movie’s based on a very flawed man who turned his life around. It’d not be as impactful if you didn’t see at least some of those flaws.

During the film, a fellow student hoping to become a priest tells Stu that’s he’s too rough-hewn to be an effective conduit of God’s message and mercy.

“No one wants to hear the Gospel from the mouth of a gangster,” he says.

“Maybe that’s exactly what they need,” Stu says.

But I think there’s truth in both of those statements.

For some, to hear the Gospel from a character like Father Stu—a man who’s obviously been around the block a few times and made a few wrong turns—can be beautiful. It can remind us that God came to save not the saints, but the sinners. That God knows the gritty, messy realities of life far better than we often do ourselves.

But our faith also reminds us that we’re not just creatures of fallen flesh. We’ve been imbued with God’s Spirit, too. And while we can’t hope to be completely pure in this life, we can aspire to be a little purer, a little better, every day. And that means being mindful of what we say, how we act and, yes, what we watch.

I found a lot to like in Father Stu. It’s funny and faithful and, ultimately, deeply moving. But it’s also very messy. And not everyone wants, or needs, to be subjected to such messes, even with this story’s holy purpose.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.