A man goes to find his reclusive brother in an attempt to help the brother’s son. Their time together plays out as both an emotional and physical battle. The movie is thought-provoking, beautifully filmed and well-acted. But it’s also profanely foul and filled with angry outbursts against God and people of faith.

Jem has to go find his brother, Ray. It’s the only thing to do.

It’s not that Jem owes Ray anything. Ray was the one who ran off and abandoned his pregnant wife, Nessa, twenty years ago. And in turn, Jem was the one who took Ray’s place in the family and picked up the pieces: He cared for Nessa, married her and raised Ray’s son, Brian, as his own.

However, it’s because Jem is such a loving and caring guy—a man of consistency, a man of earnest faith—that he has to go find Ray. Because Brian is in trouble.

Brian has grown to be a strong but rebellious young man who has followed his biological father’s path into the military. And Nessa believes that if Ray met him, talked with him, Brian might find some small semblance of peace.

In a way, Nessa’s desire for them to seek out Ray says something about how she views Jem and his role in Brian’s life. Nonetheless, Jem will go.

Now, no one quite understands why Ray left, though they know something catastrophic must have happened. And Jem really has no idea where his brother is living in the vast, heavily wooded Irish countryside. For that matter, it’s been 20 years. Who knows what two decades of living as an isolated hermit will have wrought. But Jem does have some map coordinates his brother gave him, and that will point to the approximate spot.

When Jem arrives, the two meet wordlessly. Ray fixes two mugs of tea. They share the same solitary spoon. Jem hands over Nessa’s letter and waits. Ray tosses the letter aside, unopened.

They sit. They look. This is the way of things with these two men: so much to say and so much unsaid. So Jem waits. And hopefully they’ll eventually unpack what broke one man, in an effort to put the pieces of another back together.

Jem may be a second choice; he may be the less interesting of the two. But piecing things together is what Jem is good at.

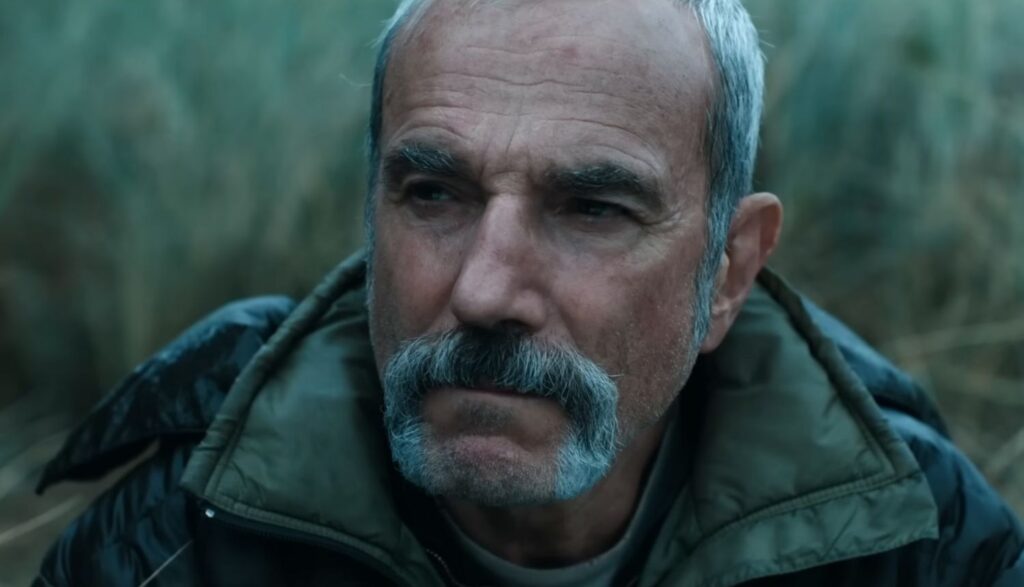

Jem is quiet, cool and caring, and he gives his estranged brother time to accept his sudden appearance. He gives Ray an opening to state his case for leaving in the first place. Ray, on the other hand, is aggressive and fiery. We can see that he is deeply troubled. But with time, the two work together to take steps in positive directions.

We watch both a figurative and very real wrestling match (sometimes coming to actual blows) as the two men come to grips with venting pain and agony from the past. And this plays out as a cathartic process that might lead to real healing. (Though we don’t see that fully satisfied.)

Ray is volatile in his opposition to faith. He chides and mocks Jem for his faith. On the other hand, Jem prays several times: praying for his trip, praising Jesus for blessings and his life, lifting up his wife and family, and giving thanks before a meal. Jem also suggests that “some kind of demon” has ahold of Brian. We see Nessa silently praying, too.

Ray holds a personal anger against God because he was sexually abused by a local priest as a child. (Ray delivers a monologue about his revenge on the priest that is wincingly foul, emotionally devastating and grotesquely scatological in its content.) And later, after Ray reveals another emotionally traumatic experience that impacted him in terrible ways, Jem tries to comfort his brother. Ray lashes out in return, profanely declaring that he doesn’t need Jem’s or God’s absolution.

In a symbolically parallel scene, Nessa talks to her son, trying to explain that for all of his flaws, Ray gave Brian life. In return, Brian shouts that all his father gave him was a curse.

The film uses images of nature—broody cloud-filled skies, acres and acres of wind-stirred trees and a massively destructive hailstorm—to convey the volatility and beauty of God’s creation around us.

Ray experiences some dreams that contain glowing, ethereal images that could be seen as spiritual communications. In one, for instance, he sees a younger version of Nessa hovering at the foot of his bed. Another depicts an abstract form of light with an internally beating heart and a somewhat human face. Ray identifies this as Brian.

Ray and Jem strip down to shorts to swim in the ocean and bathe naked in a river. Ray dreams of a glowing, abstract, one-dimensional form that has hanging genitals. Ray also tells a story of exposing himself to someone.

Ray tells a vivid, profanely worded recounting of how a priest sexually abused him when he was a boy. Then he tells how he made that offending man suffer physically after meeting him again as an adult. Jem notes that their dad used to pray for Ray; Ray retorts that “he prayed every time he took his belt off.”

Ray also describes a devastating scene he encountered, where an explosive device obliterated one man and left a second ripped open with his “innards spilt out.” That intensely suffering man begged to be put out of his misery, and when he was, it was labeled by officials as a war crime. We hear of other men dying in war.

After nearly killing a man with his bare hands, we see Brian’s badly bloodied knuckles as he talks about the incident. The movie’s opening scene displays a child’s drawing of men shooting and killing others in war. There are bloody bodies, severed limbs and a mother holding her murdered child in the crayon drawing.

Jem and Ray get into a fight, punching and battering each other to the ground until one of them submits.

The film contains nearly 50 f-words and half a dozen s-words, along with a handful of exclamations of “b–tard.”

Twice during Jem’s stay at Ray’s cabin, the brothers drink glasses of booze. And they also walk to a nearby town and pub to get glasses of beer. The two dance about drunkenly to loud music. Brian and a friend smoke cigarettes.

Nessa talks to Brian, declaring that Ray’s fellow soldiers never suggested that he should be ashamed of anything he did during combat. But Brian points out that Ray abandoning his wife and son was nothing to be proud of either.

In the summer of 2017, highly respected actor Daniel Day-Lewis declared his retirement from fame and the hamster wheel of Hollywood. But eight years later, he returns to star in and cowrite the directorial debut of his son, Ronan Day-Lewis.

The father and son’s collaborative effort is an unconventional and emotionally discordant film that some won’t fully grasp—and many won’t have the patience or stomach for.

The drama itself feels very much like a caustic chamber play that relies on space, silence and things left unsaid. But that dark and intimate foundation is garnished with sweepingly beautiful, broody cinematography and loud, clashing instrumentals: surprising movie elements that jar the viewer.

At its core, Anemone is an examination of a broken man’s self-imposed purgatory. A person of faith might see that as an illustration of man’s struggle with sin and with God. But the movie refuses to let any potential spiritual messaging come easy.

Anemone’s sparse dialogue is stitched together with profane fulminations against faith, scatological rants and foul invectives in opposition to any manner of forgiveness. It’s the sort of stuff that a faithless man stewing in his own form of self-abuse might do. And the director and cast portray that volatile self-abuse with an artistic flair.

Of course, that means that viewers who stick around will have to stew in that same pool of loathing and profanity for two hours. With only a brief hint of hope by the movie’s end.

That’s a difficult ask, no matter how good the acting is.

After spending more than two decades touring, directing, writing and producing for Christian theater and radio (most recently for Adventures in Odyssey, which he still contributes to), Bob joined the Plugged In staff to help us focus more heavily on video games. He is also one of our primary movie reviewers.