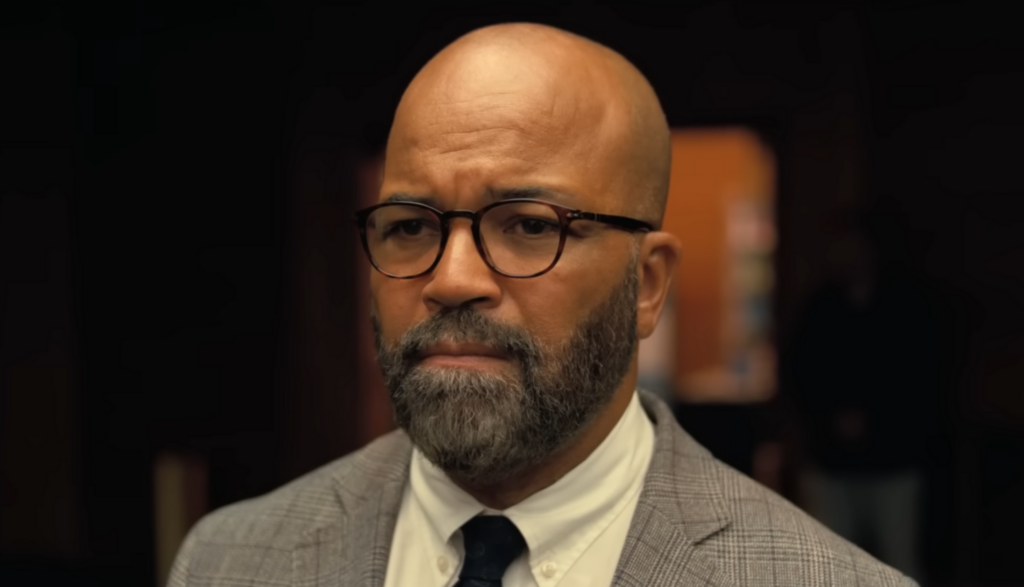

Thelonious “Monk” Ellison is a writer, and a good one. Everyone says so. Well, at least everyone who reads his books. All three of them.

Monk sells more books than that—but not many more. And certainly not enough to make publishers happy. His latest manuscript was just turned down by yet another publisher.

“They want a Black book,” Arthur, Monk’s agent, tells him.

“They have a Black book,” Monk says. “I’m Black and it’s my book.”

But for publishers, Monk’s book isn’t Black enough. His writing contains a disturbing lack of drug dealers and unwed mothers, they say. Hardly any of his characters are shot to death by police. When he finds his books in the African American Studies section at a local bookstore, he lambasts the clerk. “The Blackest thing about this book is the ink,” he says.

Monk may be Black, but he never seems to write about the Black experience. At least, not the experience that publishers want to publish and people want to buy.

No, people want to buy books like We’s Lives in da Ghetto, the runaway bestseller by Sintara Golden. The novel is packed with drug-filled streets and deadbeat dads and terrible grammar (“Yo, Sharonda! Girl, you go be pregnant again?”). And readers are gobbling it up like barbecue brisket at a church potluck. Meanwhile, Monk’s nuanced characters or complex narratives are treated like rhubarb casserole.

That’s too bad, because Monk could use the cash.

His mother is sinking deep into Alzheimer’s, and she needs special care. Lisa, Monk’s incredibly capable sister who was caring for their mom, unexpectedly (and inconsiderately) died while Monk was paying a family visit. Monk can’t expect any help—financial or otherwise—from his unreliable brother, Cliff. That means that Mom’s care falls on Monk—and that care could be expensive.

Monk knows that if readers knew anything, his books would run circles around the likes of We’s Lives in da Ghetto. His mom would be set. He’d finally get the recognition he deserves.

But people don’t have taste. They don’t have discernment. So one night—after perhaps one nightcap too many—Monk sits down at the computer and begins to type.

My Pafology by Stagg R. Leigh.

The words flow out his fingers, shaping a world filled with drugs and murder, racist cops and corner dealers. Rap thumps on the pages. Sirens howl in the paragraphs. Monk doesn’t know much about the world he’s writing about, but he trots out every trope and stereotype he can think of.

He intends the thing to be one big joke, a jab in the ribs of everyone who lapped up We’s Lives in da Ghetto, everyone who felt that a great Black character needed a gold grill and a bullet scar. It’ll make the lit intelligentsia realize just how myopic—and perhaps, how unintentionally, paradoxically racist—they were.

But when the unpublished book starts making the rounds, no one’s laughing. They love it. So real! Publishers say. So true! So … Black!

It all makes Monk want to roll his eyes and pull back the book—until they start talking about how many copies they’ll be rolling out.

My Pafology might be a joke. But as Arthur says, it’ll be the most lucrative joke that Monk has ever told.

American Fiction satirizes both the publishing industry and, perhaps, American racial attitudes themselves. As publishers sought to represent more “authentic” stories of color, they elevated only certain stories and pigeonholed what the “Black” experience looked like.

But it’s also a story about family. And that’s where the movie’s real heart resides.

Monk has often pushed away his family, and he makes the trip back to visit his mother and sister only reluctantly. But when his sister’s death forces him to take a more active role, he begins to repair those important relationships and heal old wounds. He shows deep concern and compassion for his mother; he walks the family’s longtime housekeeper, Lorraine, down the aisle at her wedding. He and Cliff even grow closer.

“People want to love you, Monk,” Cliff tells him. “You should let them love all of you.”

It’s a pretty insightful observation, given that Cliff knows nothing about Monk’s literary alter ego, Stagg R. Leigh. But Cliff knows that Monk can make himself a difficult person to love. He’s often a jerk throughout the film, and he damages some important relationships because of it. But slowly, Monk comes to understand how selfish and abrasive he can be—and he tries to take steps to be less so, asking forgiveness that he so fervently needs.

Monk and the rest of his family participate in a seemingly nonreligious memorial service as they toss a loved one’s ashes into the ocean. A wedding features a pastor.

Cliff is gay. We hear that his wife left him when she discovered him in bed with another man, and Cliff seems determined to push his homosexual love life into hyperdrive—as if making up for lost time. When Monk goes to the family beach house one day, he discovers that Cliff and two apparent lovers have been vacationing there for a few days: All of them are in tight-fitting underwear and nothing else.

Cliff’s sexuality has been a point of friction within the family, and Agnes (Monk and Cliff’s mother) unknowingly says some hurtful things that pushe Cliff away. But when Cliff and his lovers are found at the beach house, Lorraine, the housekeeper, insists that all three stay there as welcome guests.

Monk also lands in a relationship. Coraline lives next to the Ellison family’s beach house, and the two meet when Monk helps pick up some dropped groceries. Soon, they are spending the night together (we see Monk putting on a tie one morning in her house), and their relationship continues to grow and change throughout the film.

We hear references to unwed mothers and irresponsible fathers. Lisa and Monk have some joking conversations about sex, and Lisa’s farewell letter (read at her memorial service) includes a graphic reference to sex with Idris Elba. There’s a reference to masturbation.

When Monk begins writing My Pafology, two of his characters appear and act out the scene he’s writing. One shoots another in the gut, and the man engages in a prolonged death scene—pretty appalled that Monk would kill him off so quickly. Another man is shot to death by police.

Lisa (Monk’s sister) suffers a heart attack while she’s having lunch with Monk. We see her clutch her chest, and then, in the hospital, see her bare foot after doctors say there’s nothing more they could do.

Monk’s alter-ego, Stagg R. Leigh, is given a fictional biography—including that he’s actually on the lam. When a film producer meets with “Leigh” (as he considers to buy the film rights to the book), he asks about a previous prison sentence, and whether it was for murder. “You said that, not me,” Leigh says—confirming the producer’s suspicions while steering clear of an outright lie.

We learn that Monk’s father committed suicide in the beach house—shooting himself in the head. When Monk visits his mother, he’s told that she attacked an orderly. A person is pushed into a pool.

Monk’s book—the one written by Stagg R. Leigh—doesn’t stick to the name My Pafology. Desperate to kill the book before it’s published, Monk (as Leigh) insists the name be changed … to the f-word.

The publishers accept, and we see and hear that word aplenty because of it. All told, we hear the f-bomb spoken about 50 times, and perhaps see it as part of the book cover a handful of others.

We’re treated to about 25 uses of the s-word, as well as repeated uses of several other profanities including “a–,” “b–ch,” “d–n” and “p-ss.” God’s name is misused seven times (thrice with the word “d–n”), and Jesus’ name is misused four times.

The n-word is frequently used, too—most notably in the opening scene. Monk (who’s also a college professor) is leading his class in discussion of a story that uses that word, and one student vociferously complains that she finds the word offensive and would rather not discuss the story at all. Monk tells her that he’s gotten over it—and suggests that she should, too.

Cliff snorts what appears to be cocaine. Characters smoke marijuana. Monk drinks, sometimes heavily. Many other characters drink, too—at dinner and parties, primarily. Drug use is referenced in books and discussions about said books.

Agnes is heavily sedated in a care facility. A character smokes.

Lisa works at a pregnancy center, and she and Monk both clearly support abortion rights. (Lisa cracks a Roe v. Wade joke.)

Monk suffers from depression, it seems, and he doesn’t quite know how to manage it. It’s suggested that he’s following in the steps of his often-angry, suicidal father.

Monk urinates in a bathroom.

It’s fitting that American Fiction deals with the writing and publishing of books. Not only is this film based on a book itself (Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure), but you could write a book unpacking and exploring its themes.

Its biggest themes revolve around race and racism: It’s a satire targeting both the publishing industry but, more broadly, white guilt and conceptions of what Black culture is. It’s telling that when Stagg R. Leigh’s novel comes up for a prestigious award, it’s the white judges who insist it deserves to win, while its two Black panelists want to pass. Monk and Sintara Golden (author of We’s Lives in da Ghetto) engage in a spirited conversation on the Black experience and its place in literature—a conversation that I found fascinating.

American Fiction offers plenty of racial, social and relational wrinkles, but the biggest takeaway is an important one: Stories are both universal and collective—sometimes predictable, always unique.

Monk knows that plenty of Black men have indeed lived in drug-filled neighborhoods and wear gold chains around their necks. But he knows—from experience—that some Black men grow up in upper-middle-class security and travel to the family beach house for the summer. And while he might not know the tragedy of a family member gunned down in a drug deal gone wrong, he does know tragedy. We all do. To pigeonhole people into a certain genre, well, he feels that’s just wrong.

But while American Fiction gives us plenty to ponder, and while it’s undoubtedly a well-made, wickedly biting and surprisingly poignant film, it comes with plenty of issues, too.

We see same-sex relationships, drug use and ticklish plot elements that viewers will need to consider before seeing this film. Moreover, American Fiction is littered with profanity.

It’s there for a reason, I think. Monk gives his book an obscene four-letter name, perhaps, to stress the point he’s trying to make: Just as people are unique, so our language is diverse. And yet people resort to the same handful of profanities to express themselves—just as we resort to tropes and stereotypes to define the people around us.

But reason or not, those obscenities are still inescapable, and the biggest reason why this film is rated R. And for many, it’ll be reason enough to keep American Fiction on the shelf.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.