There are places, even now, where you can’t be found.

No Wi-Fi, no cell service, no corner Starbucks. There, in the dark of the forest, the edge of the plain, the cracked core of the desert, you could sit for days, weeks, and never see another soul. These are places so lonely your skin tingles from the silence.

Aron Ralston lives to experience such places—to wrap himself in solitude and see nothing but rock and water, hear nothing but wind and rain and the thump of his own heart in his ears.

He’s no recluse. He has friends, a family. And yet, Aron loves to be alone. It’s part of who he is, and who he wants to be—an adventurer who can survive and thrive with only a compass and a bottle of water. No one else could appreciate these quiet places as Aron does—places in which the membrane between heaven and earth seems tissue thin.

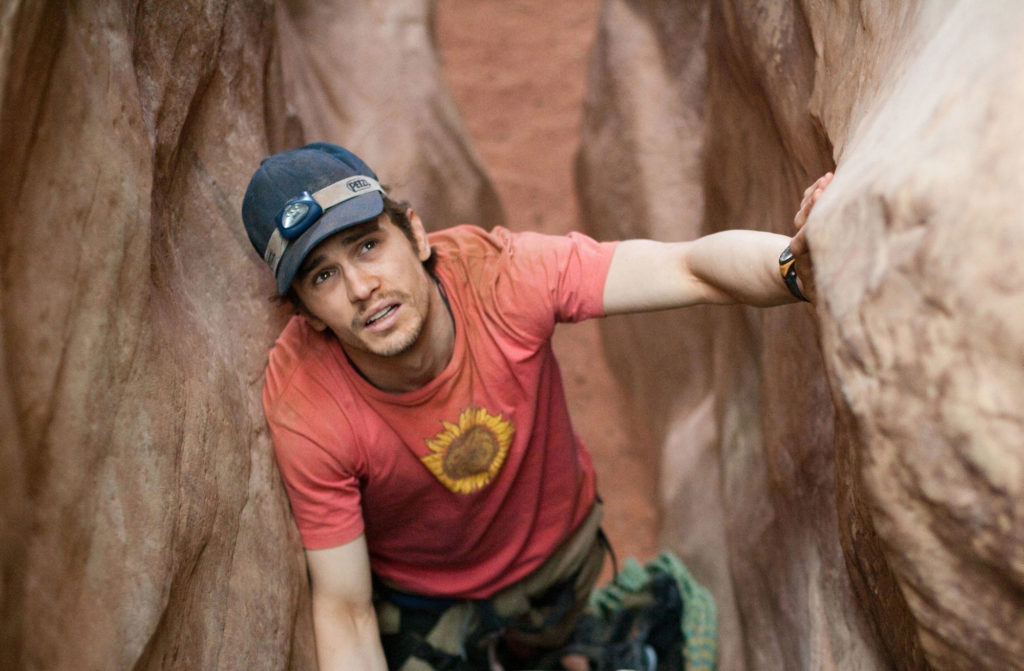

On April 25, 2003, Aron left for such a place—the lonesome canyon country of Utah. It was one of his favorite haunts, and he drove most of the night to get there. He biked. He walked. And he ran into a couple of girls—hikers who got lost—with whom he spent a few charming hours swimming in a hidden pool. And then he took off to do what he came to do: drop into Blue John Canyon and explore its hidden crevices, its secret stones.

He left no note. He didn’t tell anyone where he was going. His independence was an honor badge, his solitude a medal.

And so, when he slipped and fell … when that rock tumbled down after him and landed on his arm … when it pinned him to the side of the canyon … when it trapped him in its shadowed confines … he knew, almost immediately, that no one would come looking for him. He was alone, with little food, little water, and only a bargain-basement utility tool to somehow work himself free. If he was to survive, he’d need to make it happen on his own. And if he didn’t—well, it might be months before anyone even discovered his body.

There are places, even now, where you can’t be found.

127 Hours is based on the real-life story of Aron Ralston, an adventurer who, after spending five days pinned down in Blue John Canyon, freed himself by amputating his arm.

It’s an amazing, if grisly, story, and the corresponding movie has all the positive attributes you’d expect: The cinematic Aron shows an unquenchable, almost unimaginable (under the circumstances) desire to live, and the story is a study in courage coupled with a steely calm. It’s one thing to sever a limb. It’s another to plot and plan exactly how best to do it—not to mention marshalling your limited resources well enough to survive for five days under such extreme conditions.

Along the way, Aron finds a new appreciation for his family, confessing in a videotaped message that he sometimes took them for granted. “I love you guys,” he tells them, “and I’ll always be with you.”

Through Aron, we also learn a very important lesson: If you’re going on a solo adventure, always leave a note. Oh, and try not to be quite so reckless, because the rawness of nature always has the upper hand.

In his darkest hours, the Aron Ralston we see on the screen does not recite Bible verses, as some of us might be inclined to do. But 127 Hours still contains an undercurrent of unnamed faith—a sense of the divine that strikes a certain chord.

“He’s wild, you know,” Mr. Beaver says in C.S. Lewis’ book The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. “Not like a tame lion.” The quote ran through my mind as I watched Aron, pre-accident, run his hands over smooth canyon stone, as if trying to touch a wilder truth lurking behind the rock. There’s something spiritual in Aron’s love of nature. And once he gets trapped, we see him embrace its microscopic nuances. A raven soars past every morning. Sunlight cascades into the crack like a liquid, bathing Aron in its welcome warmth. All these things Aron, even in his horrible predicament, appreciates, soaking them in as sublime reminders, perhaps, that he’s not entirely alone.

He has a “premonition” of his future child—a premonition that pushes him to do the unthinkable. And while Aron does not unmistakably pray, there seems to be something at work in his mind, if not his heart. “Please,” he whispers, as he tries to retrieve his multipurpose tool with his toes. “Thank you,” he says, when he finally frees himself and staggers out of the canyon.

“I may never fully understand the spiritual aspects of what I experienced,” the real Aron Ralston told the Los Angeles Times shortly after his ordeal, “but I will try.” He said that, curiously, he experienced a strange surge of energy the third day of his entrapment—a day that coincided with the National Day of Prayer. “The source of the power I felt was the thoughts and prayers of many people, most of whom I will never know.”

Before succumbing to the stone, as it were, Aron encounters two pretty women and promises them an experience that’s “the best you can have with your clothes on; but it’s better with your clothes off.” He then shows them the way to a hidden pool, where they all swim. Aron takes off his shirt and one of the girls strips down to her underwear. Aron records the experience on his video camera, and later, when he’s trapped, he replays the images, pausing for a lingering look at exposed cleavage. He moves his hand toward his crotch before he utters a frustrated “no!”

Aron also has brief flashbacks to an experience he had, perhaps in college, when he and loads of other men and women in a van stripped down to their skivvies (in the jumble, some of the women appear to be topless) and then dove into a freezing lake. Later we see Aron and one of the girls lying together, both apparently naked underneath some blankets. She runs her fingers over Aron’s chest and asks him what’s the key to letting her in. Then she reaches down, under the blanket and past Aron’s waist, and exclaims that she just found it.

It’s been reported that Aron’s amputation sequence has made moviegoers faint or vomit. The theater in which I saw the film actually had a warning posted to the door.

It’s a three-minute montage, and it is indeed brutal. Aron breaks both bones in his forearm, then gets at gouging through the skin and muscle surrounding them with a painfully dull blade. It’s bloody, gory work. We see his face and hands streaked with blood, and watch as he cuts through a spaghetti-like bit of nerve running through the core of his arm.

Because the film is so tightly focused on just this one man and his arm, you find that you become extremely empathetic to the horror Aron is going through. You feel his pain—almost literally—far more than you do while watching a run-of-the-mill horror flick. But for all its brutality, those three minutes of screen time pale in comparison to the hour Aron spent actually performing this life-or-death surgery.

A few other scenes to note: When the boulder first crashes down on Aron’s arm, we don’t see the impact, exactly, but we do see a smear of blood against the wall and notice his thumb grotesquely sticking out of the paper-thin space between rock and wall. (The thumb later turns a sickly gray.) When Aron decides to cut off his arm, he finds that his knife blade—which he’s been using to chip away at the rock—is so dull it won’t penetrate his skin. So his first amputation attempt results in only a handful of pinkish-red scratches. He resorts to using the “weapon” as a blunt dagger, stabbing it down hard into his flesh. Dark blood wells from the wound, and the camera takes us underneath the skin, too, showing the knife touch bone.

In a bit of foreshadowing, Aron takes a tumble on his mountain bike—an accident that might’ve given other riders a bit of pause, but Aron simply smiles and takes a picture of himself lying in the dirt.

Aron and others say the f-word about 15 times, the s-word three times and “d‑‑n” once. We also hear both God’s and Jesus’ names abused.

Aron’s refrigerator is stocked with beer, and he drinks wine and beer in both flashbacks and feverish fantasy. Girls invite him to stop by a party to have a beer.

Aron lies about being a guide. To survive, he’s forced to drink his own urine—liquid he’s been collecting in his camelback for just such an emergency. “Chill like Sauvignon Blanc,” he says, and the camera makes a stylized point of watching the yellow liquid gush and dribble into his mouth. We see him urinate at one point. And we hear him talk about waiting to defecate until he’s free.

In small ways, 127 Hours is about life, faith, family, the importance of community, the struggle for meaning and the inherent fallibility of living life alone.

But mostly it’s about a guy who hacks off his own arm.

“You know it’s coming,” writes Entertainment Weekly columnist Mark Harris. “In fact, it’s probably why you will either go or decide not to go in the first place. You may wait in anticipation, steeling yourself or dreading it or tenting your eyes with your hands, but if you try to claim that what you’re watching is about anything else, you’re probably kidding yourself. The movie itself is not interested in turning that unbearable moment into a metaphor; it knows its job is to stare unblinkingly at an unimaginable event and try to understand it. Saying 127 Hours isn’t really about the arm is like saying that Jaws isn’t really about the shark.”

The scene is bloody, brutal and, for some, nearly impossible to watch. But it is not gratuitous. While some films strive to make severed limbs and bloody knives look cool or exciting or even beautiful, 127 Hours forces us to examine the horror of it all. There’s nothing aspirational in Aron’s five days of torture in Utah’s canyon country—nothing that would make someone say, “I want to get stuck just like that!” It is, however, at least in some respects, inspirational. Aron’s gumption and grit—along with his softened attitude toward his family—are most certainly moving.

I remember when the real Aron Ralston found his way out of Blue John Canyon and clambered to safety. It was a riveting story—triggering an odd blend of car-wreck curiosity and “could I do that?” consideration. From what I gather, the film stays pretty true to Ralston’s actual experience. And while director Danny Boyle (of Slumdog Millionaire fame) sticks in some artistic flourishes, he really doesn’t embellish the story much. He just shows us what happened and lets us squirm and cringe and cry.

That makes 127 Hours riveting cinema—and questionable entertainment. There is nothing particularly entertaining about watching someone slice away his own skin and sinew. It doesn’t mean everyone who decides to see it does so out of some sort of twisted morbid curiosity. But it does mean that the temptation to crane our necks and gape at the spectacle is very much present here.

For Aron, amputating his arm was certainly not entertainment. It was survival. It was bravery. It was determination. A movie can only be a pale reflection, and at best can somehow inspire us in little ways to strive for those things. At least 127 Hours does that.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.