The Beauty

FX’s ‘The Beauty’ will certainly make its viewers think about beauty and vanity, but so many ghastly content concerns make this an ugly show.

We all have scars, whether we see them or share them.

Camille Preaker has more than her share, on the inside and out. The St. Louis newspaper reporter keeps the visible ones—the words she’s carved into her own skin—hidden with long sleeves and a chilly, almost hostile reserve. The scars deep down … well, they still feel fresh and raw, despite their age. She tries to balm them with bottles—no, buckets—of liquor. But it never seems to do the trick. They still hurt, so she swallows still more.

Her current assignment isn’t helping, not in the short term at least. Two tragic, seemingly senseless murders have been committed in Camille’s hometown of Wind Gap, Missouri. Her well-meaning editor, Frank Curry, wants her to chase down the story. He knows it won’t be an easy assignment. He knows that Camille’s past is filled with ghosts and demons and festering wounds. But Curry’s not one to let those things stew. As a good news editor would believe, he thinks it’s best to get it out there, like a painful but important story. Face it. Deal with it.

“Life is pressure,” he tells Camille, not unkindly. “Grow up.”

So she goes back to where she grew up, to face the horrors of the past and present. She goes back home.

A handsome home it is, too—at least on the outside. The Victorian-era mansion is filled with the smells of fresh-cooked breakfasts (courtesy of a live-in servant, Becca), classic jazz (courtesy Camille’s polite-if-reserved stepfather, Alan) and oh-so-many beautiful things, all managed meticulously by her mother, Adora, Wind Gap’s most respected socialite.

But open up some of the home’s many closed doors, and you’ll find dysfunction and tragedy. One hides a room that belonged to Marian, Camille’s younger sister, who died from a mysterious illness when she and Camille were both still girls. Marian’s room is like a museum—left just the way it was when the girl died. Open another door, and you’ll find Amma’s bedroom. She’s Adora’s youngest—beautifully prim at home, but a wild child outside it who experiments with sex and booze and drugs.

Then there’s Camille’s own deep-pink room with the crack in the ceiling, a crack that she and Marian once traced with their fingers right before Marian died. Camille’s staring at that crack again, because she rarely sleeps these days. Not unless she passes out in her car.

But Curry’s expecting a story, so Camille has to push through her boozy haze and small-town miseries to file one. As a former resident of Wind Gap—the prettiest girl in town, it was once said—she’s got a little more leverage with the locals than a true outsider might, which gives her an informational leg up over big-city detective Richard Willis. But still, it won’t be an easy story to track or write. And she wonders whether (like her editor hopes) the time back home will help. Or will it just add more scars to her skin and soul?

Sharp Objects, based on a book by Gillian Flynn, is well-titled, and as such carries its own cautionary message to would-be viewers: This HBO miniseries may inflict its own share of scars.

We can’t and won’t deny this modern gothic mystery’s aesthetic quality. Sharp Objects is sharply written. Anchored as it is by five-time Oscar nominee Amy Adams, the performances are top-notch.

But HBO itself seems to know that this show might be difficult for many, given its themes (and often graphic depictions) of substance abuse, mental health concerns and self-harm. The show, à la Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why, offers a list of resources for those who might be struggling with mental illness.

But the issues in this show aren’t just topical or thematic.

HBO is well-known for its graphic sexual content, of course: We’ve documented that plenty in everything from Game of Thrones to Westworld, and those shows’ yen for skin has even been called out in the broader secular culture.

Sharp Objects is not, in some ways, as unnecessarily gratuitous as Game of Thrones (for which the term “sexposition” was coined). But in the first episode, it exposes viewers to something I’ve never seen on television before: The camera pans over a few magazine pictures that depict graphic, hardcore porn. I had no idea that those sorts of images would be allowed on television, even on premium cable.

Sharp Objects doesn’t turn away from violence or language, either. And as for alcohol and drug abuse … I’ve never seen more than here. Again, there’s a narrative reason for it, but heaven help anyone who might be tempted or triggered by such behavior.

Sharp Objects drills down into a quaint small town and a seemingly picture-perfect family to expose a wealth of sin and grime beneath. I’m a little like Curry when it comes to real-world issues: Better to expose them and deal with than keep them hidden. But when it comes to unearthing this sort of stuff in fiction? For our “entertainment?” Don’t see much reason to unlock the door and let it out.

Camille, a troubled reporter, is sent by her editor, Curry, to cover the murder of a girl and the disappearance of another in Camille’s hometown. In part, Curry wants the story. In part, he hopes the business trip back home will help Camille to “flush things out. Get back on your feet.” But as a series of flashbacks suggest, Camille getting back on her feet—given her strained relationship with her mother, Adora, and her well-to-do family—may be pretty difficult.

In one of those flashbacks, we see a teen Camille walk into a shed, the walls of which are dotted with pornographic images (we only see them briefly, but it’s obvious that the figures therein are nude and engaged in various sexual acts), and a shelf is covered with bloody, drying strips of meat. Modern-day Camille recalls these images, which apparently arouses her. A scene implies masturbation. She takes a couple of baths during the episode, too, and her backside is exposed in one shot.

Camille’s half-sister, Amma, and her friends dress in revealing clothes when Amma’s mother isn’t around. The father of a murdered girl believes that a gay man (he uses a slur) killed her, given that she wasn’t raped. The fact that she was murdered, not sexually assaulted, the father says, is the “only blessing” he can find in the tragedy. A bartender talks about how the establishment’s previous owners left for California, suggesting that those two men were in a relationship. “We don’t really get that type around here anymore, whatever you call ’em now,” he says. “Not that I have nothing against ’em.” He then makes a crass comment about an underage male drinker at the bar. (Camille calls him “gaybait.”)

We see the corpse of a murdered girl propped up on a windowsill. She’s covered in mud and grime. We hear how she and the other girl were strangled. In flashback, Camille’s sister Marian—apparently sick and sweating—has some sort of seizure, perhaps while she and Camille are high. Later, we see Marian’s corpse at an open-casket funeral. Other flashbacks feature a teen boy aiming a gun at a swimming Camille, and a young Camille pushing the point of a paperclip into the back of an adult Camille’s hand. (It doesn’t break the skin.) In present day, Camille’s forearm has scars that spell out the show’s title. We see blood drip in a flashback or two.

Camille’s rarely sober. She brings nearly a dozen tiny bottles of liquor with her on her trip to Wind Gap and finishes them all in a day. She goes to a bar and drinks much of the night, eventually passing out in the car. When a detective pours a couple of glasses of whiskey for the two of them but then has to leave, she quaffs hers, then takes his cup and drinks his, too. Camille buys a full bottle of vodka at 9:30 a.m., then regularly pours some of the liquid into her water bottle throughout the day. She smokes, too, and her car’s ashtray is filled with butts. Her editor is obviously trying to quit, fiddling with an empty cigarette carton and chewing on (apparently) nicotine-laced gum. Other characters, including a few who are underage, also imbibe alcohol. A friend of Camille’s offers her some sweet tea “with a little kick” in it.

We hear two f-words, five s-words and other profanities, including “a–,” “b–ch,” “d–n,” “h—,” “p-ss” and “f-g.” Jesus’ name is misused five times, and God’s name is paired with “d–n” once.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.

FX’s ‘The Beauty’ will certainly make its viewers think about beauty and vanity, but so many ghastly content concerns make this an ugly show.

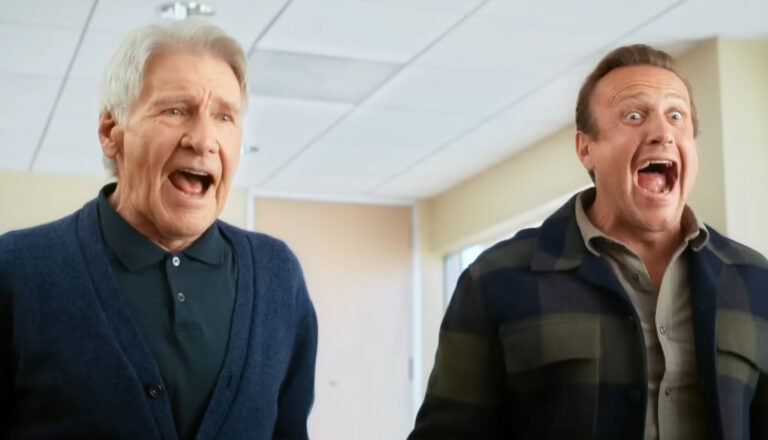

Apple TV+ seems to have a knack for creating deeply heartfelt, wildly problematic comedies. Shrinking is one of them.

‘Steal,’ an intense, nail-biting thriller, will certainly keep you engaged. But that means facing some bloody, frightening situations along the way.

For a superhero show, ‘Wonder Man’ is surprisingly light on violence, but a bit heavy on swearing, sexual allusions and meta-Hollywood references.