Life begins … when?

You look at your newsfeed any day of the week, and you know what an explosive question that is, even superficially. But dig deeper, and the answer grows even more complex. To live is not the same as to have a life. Did our life begin with conception? Our first conscious thoughts? Our first memories? Did it begin in kindergarten? In middle school? When we fell in love? Had children? Found our purpose?

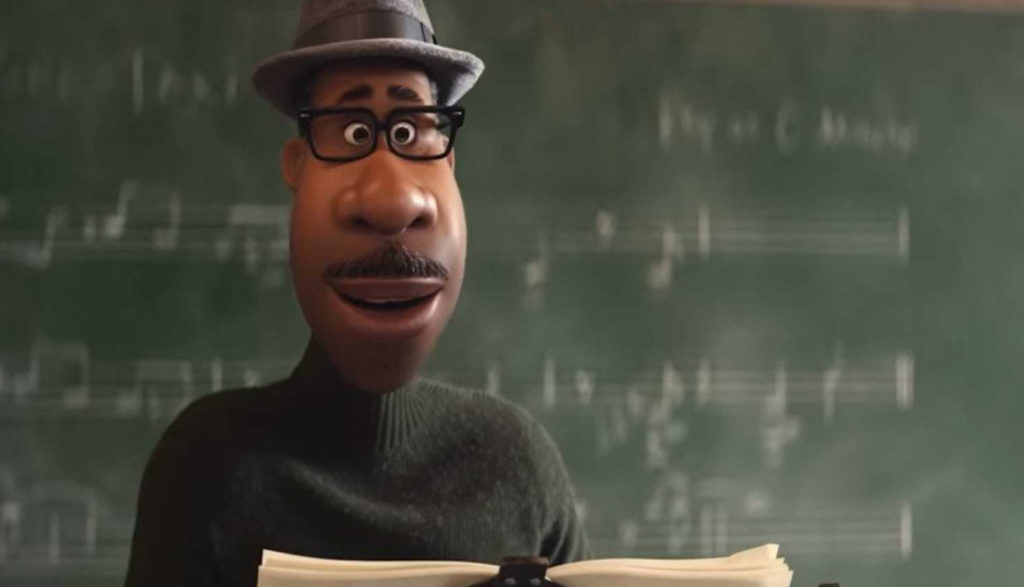

Joe Gardner is a grown man with a job, a New York City apartment and a mustache. He’s alive. But he’s still waiting for life to begin.

And then, one day, it does.

The day was no different than most, at first. Joe, a talented jazz pianist working as a middle school music teacher, is teaching a bevy of students how to carry a tune—or, at least, to find the tune’s zip code. But then Curly, an old student of his, calls and asks if he’d like to sit in on a session with Dorthea Williams, the legendary jazz musician.

Would he?! Joe races to the club where Dorthea is to play. She’s skeptical at first: “So,” she says. “We’re down to middle school band teachers now.” But when his fingers touch the ivory, her doubts drain away. She tells him the show starts at nine. Be there at seven.

Joe feels as though his life is finally beginning. He floats out of the club, as happy as he’s ever been.

And he promptly falls through an open manhole.

Next thing he knows, Joe’s riding an escalator to the Great Beyond, a massive, white-bright something, where the souls of the newly departed go.

But Joe isn’t ready for the Great Beyond. “I’m not going to die the very day I got my shot!” he protests. As the escalator slowly moves upward, Joe bounds down, down, down until finally—

Pop! He finds himself in a strange place filled with adorable new souls and caretakers named Jerry. It’s not the Great Beyond, but the Great Before, where souls are prepared for their lives on earth. (Actually, it’s now called a “youth seminar,” Jerry explains. “Rebranding.”)

There Joe finds soul No. 22, who wants to be born just about as much as Joe wants to be dead. That is, not at all.

When does life begin? Seems like neither Joe nor 22 have a clue. But here, at the end/beginning of all things, perhaps they’ll find out.

Joe’s given an opportunity to look back on his life, and he’s appalled with how little he did with his. “My life was meaningless,” he says.

But that’s not quite true.

The movie delicately suggests that he made a huge difference on some of the people he came in contact with: Curly says he never would’ve gone into music had it not been for Joe’s teaching. Another student, thinking about quitting, goes to Joe’s apartment in the hopes that he’ll talk her out of it. For Joe, teaching has always been something he’s had to do. But moviegoers see the impact he’s made on others. And even when he’s technically dead, he still makes a difference in 22’s pre-existent life, too.

That’s one of Soul’s overarching themes, in fact. In our celebrity-bedazzled world, we imagine that the only lives that matter are those that make a huge, splashy impact. Soul suggests there’s nothing wrong with wanting or having that sort of impact. But it also reminds us that those of us who live pretty normal lives can have an oversized impact on those around us, as well. And even when we fall into lives we never expected, there’s a joy and nobility in that, too.

For instance: We meet Dez, Joe’s barber, and learn that he never wanted to be a barber at all. He was hoping to be a veterinarian. But when his daughter got sick, he fell into the business. Joe feels sorry for him at first, but Dez rejects that pity out of hand. “I’m as happy as a clam, my man.” He sees his work as a way to change and improve lives. He says he makes his clients happy. “And make them handsome,” he adds.

Let’s start with the movie’s name: Soul. That metaphysical concept is integral to what the movie’s about. We’ll need to spend some time here.

Joe spends much of the time in the movie as a soul, uncoupled from his own body. As such, Soul tells us that we’re more than just our physical constructs—more than just bone and blood and a little bit of brain matter.

There’s an inherent spirituality at work here, further emphasized by the Great Beyond, the Great Before and some metaphysical planes we see. The movie never takes us into the Great Beyond, so we don’t know what lies on the other side of that brilliant white light. But clearly plenty of souls (who aren’t Joe) are quite happy to be headed there.

The Great Before is more ticklish to deal with.

The idea that a soul exists before the body’s creation isn’t new: Lots of religions embrace that concept, and the Great Before feels a little like the Jewish concept of the Guf, or “treasury of souls,” which serves as a bit of a holding house for souls waiting to be born.

In contrast, most orthodox expressions of Christian theology have rejected the notion that the soul’s existence predates conception. Thus, the ideas about the afterlife and beforelife we see in Soul share little common ground with the most traditional forms of Christian teaching.

So what do we see in this story? All of the souls in this story are paired with a “tutor” before heading down to Earth, and soul No. 22 has been paired with plenty of teachers already—including the Catholic Mother Teresa, the Hindu Mahatma Gandhi and the religiously adventurous psychologist Carl Jung. And while you could interpret the caretakers of the Great Before as angels of a sort, they come across here more like incredibly compassionate daycare workers. (There’s also a soul accountant named Terry, through whom we learn that the afterlife’s tabulation system isn’t always spot on.)

Joe and 22 also come across some spiritual planes where only the souls of the living can go. One is “the Zone,” the place where people go when they’re particularly inspired or transfixed by what they’re doing; another is a vast wasteland where the obsessed roam endlessly and sadly. Some living visitors to these planes—practitioners of various Eastern and New Age meditative disciplines who call themselves “mystics without borders”—explain that one state can lead to another. The things that we love (and that send us to the Zone) can become obsessions themselves.

All of these metaphysical layers are meant to convey some important thoughts on what it means to live in our very tangible world, by the way—not serve as a roadmap for theological truth. Still, it’s good to be prepared for some potentially robust spiritual discussions as you unpack this story’s ideas and symbolism.

Elsewhere, we see that souls can switch bodies—comically possessing them, as it were—another idea that orthodox Christian teaching rejects, by the way. A cat is shown to have a soul, too.

Joe wonders whether he’s in heaven. When a Jerry tells him that he’s not, strictly speaking, he then asks if he’s in the other place. We hear references to chakras, chanting and meditation.

Joe’s mind, we learn, is mainly filled with thoughts about jazz. But at least a corner of it is devoted to someone named Lisa. And when he and 22 find themselves back on earth in earthly bodies, 22 encourages him to rekindle what seems to be a long-dormant relationship. (Joe insists he doesn’t have the time.)

Joe rips the back of his trousers, revealing underwear.

Joe dies, of course—falling through that an open manhole after unintentionally escaping a great many situations (falling bricks, speeding cars) that could’ve spelled an even more premature doom. We just see the guy’s body vanish through the hole, though later we do see his body—barely hanging on—in a hospital bed.

New, disembodied souls resemble squishy little balls, and they’re sometimes thrown or smashed. But the souls, not having any bodies (much less nerve-endings to tweak), find it all rather fun.

A monstrous thing swallows a soul whole. A metaphysical ship sinks. We see some pratfalls and physical humor here and there. There’s a suggestion that 22 just might become a pyromaniac.

When Joe first arrives at the Great Before, he asks if he’s landed in “H-E-double hockey sticks?” The unborn souls around him, though, apparently know how to spell: They bounce around, repeating the word “hell” as a Jerry tries to explain to Joe where he is. Someone describes earth as a “hellish planet.” Besides that, we just hear a couple of uses of the word “butt.”

Jazz clubs are typically drinking establishments, and I assume that’s true of the one that Dorthea Williams and her band are playing. We don’t see anyone drink, though.

Immortal souls have no bodies, which means that food does them little good. Joe and 22 demonstrate this by each devouring a piece of pizza and having it eject—still fully formed—from their other end.

Joe lies, and both he and 22 try to game the system to get what they want. A joke alludes to body odor. Joe takes a shower, and someone mentions his rear.

I’ll just say it: A bad Pixar movie is about as common as a Latin-speaking lemming.

It’s not just the studio’s craftsmanship: It’s the storytellers’ ambition. Not content with doling out beautiful ruminations about grief and love and responsibility, Pixar dove directly into the world of emotion and feeling itself with Inside Out back in 2015. (Was it really that long ago?) Now, the animation pioneers have moved on from the heart and into the Soul.

But while the movie does indeed paint its story using many a spiritual and metaphysical brush, Soul isn’t aiming to save anyone’s. It’s far more concerned with this world than the next one, delving into one big question: What makes us tick? Or maybe more fairly, What makes us feel alive?

Neither Joe nor 22 really understand what “life” is, or what it should be. Joe has spent most of his waiting for one big moment, letting so many little ones slip by. No. 22 has never lived at all, and she can’t figure out why she’d even want to. Both characters have, in their own ways, locked themselves into a closet of secure sameness. They need to learn from each other how to use the key.

Certainly, Christian families will want to be aware of the movie’s spiritual elements before deciding to watch; and you should be prepared to talk about the story’s provocative ideas afterward. As noted, the story’s spiritual conceits here have little connection to traditional Christian understandings of these important questions.

Still, Soul strives to help us remember that life itself is a blessing, even when it doesn’t go as we planned. It tells us that lives of service can be just as rewarding as lives on stage. It encourages us to look at the world’s humblest things, be it a maple seed or a hunk of pizza crust, as something amazing—perhaps even miraculous in its own right.

Soul tells us that life isn’t just a matter of a beating heart, of drawing breath, of shuffling through each second as if we had an eternity of them. Our lives are a gift. And Christians watching this film can take it a step farther: Our lives are a gift from God.

How appropriate that his movie should be released on Disney+ on Christmas Day. It tells us that very moment, after all, is a present—and one we should open with glee.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.