Music is mystery.

It’s a series of simple sounds, created by methods most prosaic. Horsehair drawn across strings. Air pushed through a labyrinth of brass. The thump of a stick on a tight stretch of plastic.

But arranged just so, and these simple sounds can make us smile. Dance. Cry. The notes can carry our souls upward. They can pull our desires downward. They pick us up as wind does a kite, and in its melodious air we twist and turn and fly.

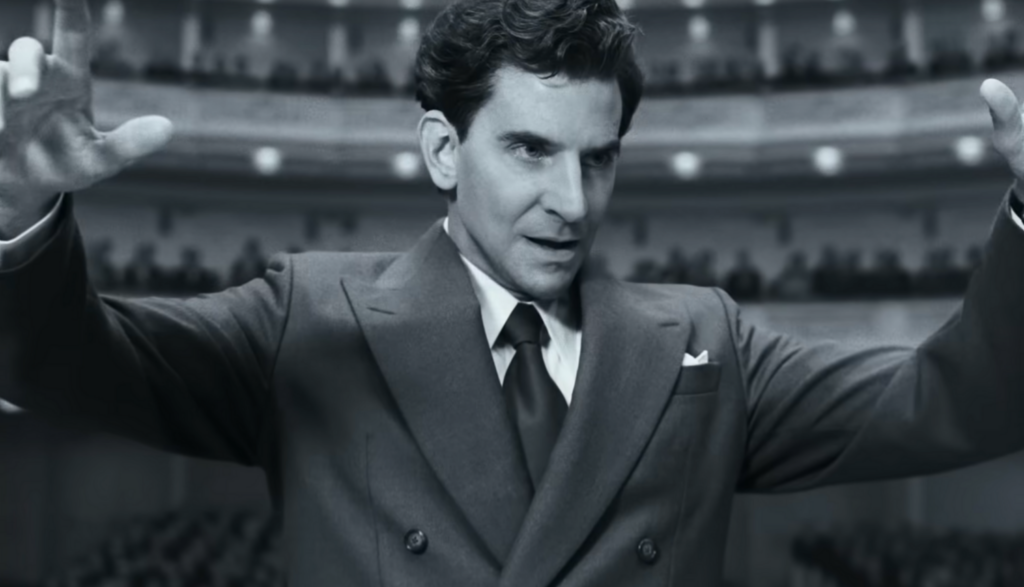

Leonard Bernstein has been carried away by music, and he carries it in turn. From the time he stepped onto Carnegie Hall’s conductor’s platform at age 25, he’s been America’s best-known classical musician. Pianist, conductor and composer, his influence has been felt from Wagner to West Side Story.

Throughout much of his radiant career, Leonard was accompanied by his radiant wife, actress Felicia Montealegre.

They met at a party, and they swirled away into a shimmering romance. They would stand on stage, reading lines. They would go to parks and sit in the grass. They shared secrets, ambitions, kisses, a bed. And in 1951, they wed and began sharing a last name, too.

“I know exactly who you are,” Felicia told him as they contemplated marriage. “Let’s give it a whirl.”

And she did know. She knew about Leonard’s attraction to men. She was steeled for the seemingly unavoidable dalliances. But she knew that he loved her—and she loved him. And as long as he was careful and discreet, all would be well.

But would it?

Perhaps there’s a reason why so much music is about love. Music and love both share that sense of inexplicable mystery.

We can try to approach relationship with reason and rationality. We can look at our partners with cool reserve; see our futures with crystal-cut clarity.

But love defies such reason. It sows it with pleasure and sorrow. Love twists reason with unexpected joys, unaccountable urges, inexplicable jealousies, undying memories. It carries us up, down, away, asunder. And it can dash not just us against the rocks, but throw our partners against them, too.

Felicia knew who Leonard was. But she couldn’t know what, over the decades, that might mean—for him, for her, for them. And perhaps, for the music itself.

The Leonard Bernstein we meet in Maestro seems to have two great loves: music and Felicia.

That love of music is unalloyed and beautiful in its simplicity. You see it on his face when he directs. And I think most folks watching the film can feel a semblance of his joy as they listen. The music here can leave you breathless.

His love of Felicia is stranger thing, and one certainly filled with distractions (as we’ll see). But the film insists it was a real love, not one staged for the press or propriety. And in a way, that love reaches its apex after Leonard and Felicia hit hard times.

While their early courtship and marriage feels light and rom-com sweet, the depth of Leonard’s love for her hits home when Felicia is diagnosed with metastasized breast cancer. During Felecia’s illness, Leonard does his best to uplift her spirits, care for her needs and comfort her. And in a rare moment alone, we see how utterly terrified and bereft he is at the prospect of her death.

“Either one believes in the divine element, or one doesn’t,” Lenny (as Leonard’s friends call him) says during an interview. The fact that he believes in said “divine element” allows him to keep going.

Lenny is Jewish, and someone suggests that he should change his last name in order to advance his career. (“To a Bernstein, they’ll never give an orchestra,” he’s told.) Felecia tells Leonard shortly after they meet that she is “fleeing puritanical origins, just like you.”

Leonard conducts orchestras and chorales that perform sacred classical music, and one of the film’s most powerful scenes takes place in Ely Cathedral in England.

When Leonard is famously given his first big break—filling in as a conductor at Carnegie Hall for a sick Bruno Walter in 1943—he gets the call while in the company of another man. The man is still in bed, and Leonard slaps the guy’s sheeted rear repeatedly in celebration.

He’s in a gay relationship with another man, David, when he begins dating Felicia in the late 1940s. Lenny (as his friends call him) introduces the two; David is shocked but polite. If Felicia suspects the nature of their “friendship,” she’s too polite and polished to show it. Later, a married Lenny runs into David and his new wife and baby. He tells the child that he slept with both of his parents. (All three laugh.)

It’s unclear how actively Lenny follows his same-sex leanings during the first decades of his marriage to Felicia. But around the mid-point of his career, we see him flirt with other men, often at parties at the Bernstein house. He sidles up close to one guest and compliments his hair, stroking it as he does so. Later the two kiss in a hallway, where Felicia spots them. (She accuses him not of homosexual infidelity, but of getting “sloppy.”)

Soon, he’s inviting the same guy, Tommy, to the Bernsteins’ country retreat with his family; he cloaks it as just bringing an entertaining gentleman into their circle, perhaps because his eldest daughter, Jamie, might like him. Felicia knows better. And when his presence seems to inspire Lenny to write one of his best works, she’s heartbroken. When the work is presented later, Lenny, Felicia and Tommy all share a box in the opera house—and Lenny and Tommy hold hands. (We see Lenny dance closely and provocatively with still another man later in the film, and we hear fleeting references to Lenny’s other same-sex affairs.)

Rumors of these dalliances are deeply unsettling to Lenny and Felicia’s daughter, Jamie. Felicia tells Lenny to lie about them—to say there’s no truth to what people are saying. And so he reluctantly does.

Felicia leaves Lenny for a time. In a bitter confrontation, she tells Lenny that he’ll wind up a “lonely old queen” if he’s not careful. During their separation, Felicia decides to date as well—but when she relates the story to a friend of hers, she reveals that her would-be suitor is gay, too, and he wanted to meet with her so that she might facilitate a meeting with a guy he liked.

All of that said, we also see Lenny and Felicia engaged in intimate moments themselves. They kiss and cuddle. We see them, before marriage, in “bed” together, though it appears to be just sheets and blankets on a bare floor. (Both are presumably naked underneath the covers, though only their shoulders are exposed.)

The artistic circle that Lenny and Felicia inhabit are far more accepting of homosexual relationships than most of the day’s society: We see same-sex couples at parties dancing and cuddling; Several decades later, Lenny and a beau go to a gay club. A man rubs another man’s foot. Apparent platonic kisses—sometimes on the lips—are planted.

While there’s not much actual violence in Maestro, Lenny confesses during an interview that both he and Felicia struggle with depression and self-destructive thoughts. “It’s hard for me to be alive,” Lenny admits. In one scene, Felicia jumps, fully clothed, into a pool and sits at its bottom. (The film suggests this is a gesture of frustration and despair, but not a desire to end her own life.)

Lenny confesses to Felicia that he sometimes dreams about killing his father. He says that he was occasionally bullied at school, and classmates (due to jealousy, he says) tried to kill him.

Eight uses of the f-word and two of the s-word. We also hear “a–,” “h—” and “p-ssed.” God’s name is misused three times, while Jesus’ name is abused twice.

Lenny and Felicia—particularly Lenny—run with a worldly crowd. Parties are a nonstop part of their lives, it seems, and they’re always fueled by liquor. (One could argue that Lenny’s own overdrinking contributes to his “sloppiness,” as Felicia might call it.) Likewise, drug use back then seems to have been a part of their lives, too. (One of them admits to taking “plenty of pills,” apparently recreationally.)

But as the decades wear on and the relationship between Lenny and Felicia strains to the breaking point, Lenny’s own life becomes increasingly hedonistic—not just in terms of his same-sex dalliances, but also his drug use. At one party, he and his friends openly snort cocaine (with the tray of drugs being held and used above Lenny’s head for a time). Referencing his increasingly more open embrace of homosexuality, hedonism and drug use, Lenny tells his students, “As death approaches, I believe an artist must cast off whatever is restraining him.”

Lenny, Felicia and most other characters smoke frequently as well. Neither of them makes do without a cigarette for long, and at least once it appears that one of them smokes marijuana. Felicia takes some pills, though it’s unclear whether they’re for a medicinal or recreational purpose.

Lenny notoriously hates to be alone—so much so that he leaves the bathroom door open when he’s doing his business to talk with whoever happens to be there. (We see a couple of scenes involving this, though nothing critical is seen or heard.)

Maestro begins with a quote from the real Leonard Bernstein: “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.”

That observation sets the tone for the emotional core of Maestro—the tension between Lenny’s love for his wife and his desire for same-sex intimacy.

Obviously, we don’t need to belabor the issues inherent with those desires here. Lenny’s sexual proclivities, along with his drug use, will make this film a no-go for many potential viewers.

But I do want to highlight another tension we find in Maestro that is more positive and, ironically, less question and more answer.

Early on in Lenny and Felicia’s marriage, she tells a friend that she can deal with Lenny’s foibles (a tacit reference to his homosexual leanings), but that’s because she doesn’t seem to care about that issue at this point. She says that she will not sacrifice anything—for Lenny or anyone else. “If I sacrifice, I completely disappear.”

When it seems that Lenny’s unrepentant lifestyle choices are indeed begging for a big sacrifice from her, Felicia—good as her word—disappears. In her absence, Lenny grows more hedonistic and out of control. He even tells a class of students that he vows to “Live the rest of my life … exactly the way that I want.”

But he breaks that self-centered vow. The two reunite. And—late in both of their lives, it seems—they come to understand that good marriages require us to give so much of ourselves. To sacrifice. To live not exactly the way we’d want, but in a way that honors and cherishes the other.

Felicia forgives and reconciles with Lenny. And for the rest of Felicia’s life, Lenny’s never far away from her. If he continued to hook up with guys during her battle with cancer, the film doesn’t show it. As she slowly succumbs to the ravages of that disease, he’s with her—with each painful step.

It’s telling that, in a late-in-life interview, Lenny seems to take a 180-degree turn from living life exactly as he might want. He tells the interviewer that he’s learned how important it is to be “sensitive to the needs of others. Kindness, kindness, kindness.”

What I write should not be taken as kudos for Felicia forgetting and forgiving Lenny’s same-sex relationships, or condoning future ones. Infidelity of any sort is a wicked blow to a relationship—so much so that it’s one of the only reasons the Bible gives for divorce. But I do want to highlight something that Maestro subtly acknowledges: Marriage, as it the case for perhaps all worthwhile relationships, is not about what we get from it. It’s what we give to it. Love is sacrifice.

Maestro, as problematic as it might be on so many levels, understands that truth. It’s too bad that lovely melody is surrounded by other, more dissonant, notes.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.