The watch is a wonder.

Even in 1942, these little pocket-sized devices were practically taken for granted. They tick as they should, tock as they ought, keeping track of the minutes and hours as if ’twas no big deal.

But open a watch up—take a look at the guts—you’ll see what a big deal it is. The gears! The springs! Each playing its own part, each moving in unison, as if listening to secret music. We see the hands move. But rarely do we witness this hidden ballet, the design behind this prosaic piece of timekeeping.

But the ten Booms do.

For more than a century, the ten Boom family has made and repaired watches in Haarlem, Netherlands, delicately placing each gear and lever where it ought to be to ensure the thing works. It’s old Casper’s shop now, though oldest daughter Corrie is practically running the place these days. Betsie helps, too—though her real gifts lie not in metal gears and gizmos, but in soft earth and gentle petals. She loves her flowers. And she, like her beloved blooms, brings fresh color whenever she enters a room.

But now, with the world in war and the Netherlands under Nazi Germany’s thumb, the ten Booms are faced with some unexpected visitors.

For starters, Casper has taken a new apprentice under his wing: Otto, a severe young German who seems as much machine as man. “I work as efficiently as possible, and I expect my time to be treated likewise,” he snaps. He certainly has no use for Betsie’s flowers, which he sees as useless clutter. But the ten Booms are determined to shower every guest with hospitality—even suspected Nazis. So Betsie merely puts the flowers on another table: “You can use them whenever you find them most efficient for you,” she gently chides.

But soon, other visitors come: Jews, hungry and scared. Word of the ten Booms’ hospitality has gotten around. And even though pragmatic Corrie has concerns about drawing unwanted attention, Casper insists on keeping the door open.

“In this house, God’s people are always welcome,” he says.

For those familiar with the story of Corrie ten Boom, you know what follows: lives lost, lives saved. Broken hearts and buoyant hope. A powerful story of sacrifice, forgiveness, redemption and purpose.

When Otto first came through their door, Corrie said, “I cannot see what good can come of it.” When the Jews came, too, she struggled to see her own worry.

But behind it all, something—Someone—was at work, moving the gears to create a wonder.

Many of us have probably heard of Corrie ten Boom, even if we don’t know much about her story. Her book The Hiding Place (upon which this stage-to-screen production was based) chronicles her and her family’s work to save Jews during World War II (about 800 were rescued due to the ten Booms’ work, the film tells us) and her subsequent experiences in a German concentration camp. Throughout it all, she clung to her faith, and she became practically a Protestant saint, knighted in Netherlands for her work and honored by Israel, which named her one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

But Corrie doesn’t begin her journey in the film as that beloved hero. In some ways, she’s reluctantly dragged into heroism by her father and sister.

Casper sets the example, of course—bravely welcoming Jews into his shop despite the dangers they bring with them. But Casper doesn’t restrict ten Boom hospitality just to the persecuted: He insists on showing it to the persecutors, too. And that includes being kind to Netherlands’ widely despised occupiers, the Germans.

“When we find something in the world that is wrong, we must not hate it,” he says to Corrie in a flashback. “We must help it to become something different. … To see something rightly, you must see it with love.” That sensibility seasoned his life and set this redemptive story to ticking.

Betsie takes that philosophy to heart. When Casper acknowledges that he’s old, and that his daughters will likely live to face far more repercussions than he will, Betsie doesn’t flinch at what she sees as her God-given responsibility to help. “Christ stayed in the garden when he knew they would come,” she says, referencing Gethsemane and the Romans. “I will stay in my home and hope they will not.”

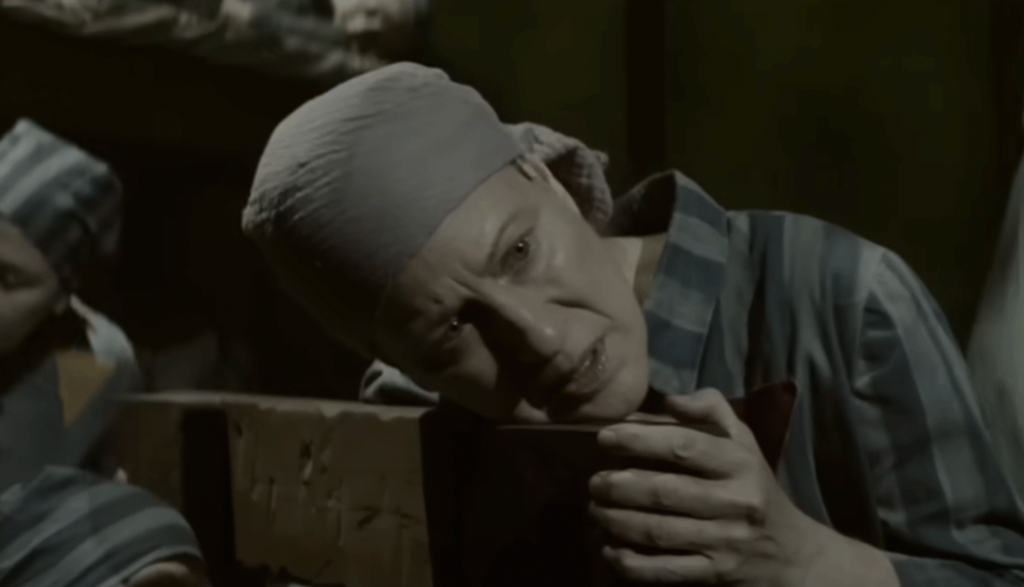

And even after they, the Nazis, do come, eventually taking Betsie and Corrie to a concentration camp, Betsie’s faith and even optimism remains. She talks about how the very fleas are her barracks’ guards, keeping the Nazis at bay. She insists that even in that dark place, there is hope and purpose. And in so doing, Betsie infuses those around her with hope and faith as well.

But if Casper and Betsie serve as the ten Booms’ heart, Corrie provides the family’s backbone. The pragmatic Corrie finds a way to feed all her unexpected gifts (through a bit of subterfuge and arm twisting). She cares for Betsie when she falls ill in the concentration camp. And in the end, she shows a remarkable capacity to forgive.

Obviously, many of the movie’s positives walk hand-in-hand with its Christian ethos. All three of the ten Booms are motivated by their faith to do what they do: Without that faith, there is no hiding place.

Every night at dinner, the ten Booms read from the Bible. As such, we hear many passages throughout the film—most of which reflect the difficult season this family and their guests find themselves in. The ten Booms never try to convert their Jewish guests, but they do invite them to read Scripture aloud—with Casper suggesting something from “one of the prophets” at one juncture. They invite Otto to participate in their nightly reading, too. But Otto calls the Bible a “book of lies” and flatly refuses.

“We have learned better than the keeping of fairy tales,” Otto says.

“In Holland,” Casper gently cautions, “we respect even those with whom we disagree.” (Later, when Otto talks with a fellow German about his apprenticeship with the ten Booms, he’s asked whether the family was Jewish. “No, but they were almost as bad,” Otto says. “They tried to read the Bible at me.”)

The Nazis we meet throughout The Hiding Place have little time or patience with Christianity. But one Nazi inquisitor cunningly tries to use Corrie’s faith against her. He tells her that lying is a sin. He reminds her that the Bible commands the faithful to respect leaders placed in authority. And when that doesn’t seem to work, the Nazi suggests that if there is a God, He’s shown nothing but contempt for the plight of people such as the ten Booms.

“Before the end, you will see much more of what your God is willing to allow,” he warns.

Betsie proves to be a spiritual counterbalance. Corrie manages to smuggle a Bible into the concentration camp, and Betsie reads it out loud to anyone who’ll listen. (The number of interested listeners grows—as does their faith.) When communion wafers are also smuggled in, Betsie (with some hesitation) leads the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. She sees blessings everywhere. She clings to a simple truth: “There is no darkness so deep that He is not deeper still.”

Corrie and Betsie have a brother, Willem, who announces he’s leaving the ministry to help the elderly. Casper seems a bit upset with this career choice at first, but Willem’s work proves to be a key piece in Netherlands’ underground work against the Nazis.

While The Hiding Place (the title of which is itself taken from the Psalms) is a Christian story, we see some Jewish faith practices as well. For instance, a woman lights a candle and covers her eyes as she recites a blessing.

None.

Obviously, Nazi concentration camps were places of unimaginable cruelty, violence and death. We’re spared graphic visual depictions of such violence, but certainly audiences will get a sense of the trauma and tragedy there.

Corrie tells us, for instance, that the Nazis took everything from their prisoners—including the gold fillings in their teeth. We see women grasp the sides of their faces in unison, illustrating the pain and loss. In another scene, a man is tortured by Nazis as sort of an echo of the crucifixion. A Nazi pulls out a gun and shoots a prisoner—apparently killing her. A prisoner is struck, almost triggering a violent reaction in another prisoner.

Outside the camp, we see evidence that a man was roughed up by Nazi agents. Someone dies from sickness. We’re told that an elderly man died after 10 days in Nazi custody and was then buried in an unmarked grave.

None.

None.

While certainly a necessary part of her work, Corrie does do things that would run counter to biblical teachings. She and another person essentially “steal” ration cards to feed the ten Booms’ Jewish guests. They lie to the Nazis to keep their secrets safe. And while in a concentration camp, Corrie and others work to build ultimately faulty radio equipment, knowing that the equipment will fail the Nazis. (Likewise, Betsie and others knit stockings for Nazi soldiers—stockings that can’t possibly keep feet warm.)

We hear a bit about the conditions in the concentration camp, including the lice and the cold. Every prisoner has a colored triangle embroidered on their prison garb, indicating what “crime” they committed against the Reich. Red indicates a political prisoner; green mean they’ve actually broken the law; yellow means they’re Jewish.

Corrie ten Boom published her autobiographical The Hiding Place in 1971. (The first cinematic version of this story followed in 1975.) It is, literally, her story.

But in this new stage-to-screen take on that story, Corrie ten Boom is not its hero. That title goes to her father. Her sister. To God Himself.

No, Corrie is a lot more like … me. Perhaps you. When someone’s unkind to her, she wants to be unkind right back. When someone demeans her faith, she wants to lash out. When she’s called to take a dangerous stand for righteousness, we can see the nervousness in her. The pragmatism. The “wait a minute” hesitation.

Watching the production, I was struck by the contrast in the ten Boom sisters. They reminded me of Jesus’ friends, Martha and Mary: Betsie as Mary, sitting at the feet of Jesus while Corrie, as Martha, bustled about.

And that bustling makes sense, in a way. Corrie, not Betsie, was a real watchmaker. She was licensed as such in 1922—the first woman in the Netherlands to receive such a distinction. Her livelihood was predicated upon precision and careful consideration and time. She understands the work that it takes to keep the watch going. She knows that the watch will stop unless you wind it.

In The Hiding Place, we see Corrie distracted by life’s gears, the springs, the myriad things that might throw the whole works off. She loves that Betsie loves her flowers—but she, like Otto, can sometimes lose sight of their necessity.

That makes Corrie, in the movie, not an unreachable hero of faith, but a woman that we can understand and sympathize with. So when she makes significant decisions and sacrifices—even in the midst of doubt and pain—maybe somewhere deep inside us, we realize that we can make a difference, too.

The Hiding Place features some strong performances and creative stagecraft. And while the stage setting may push some would-be viewers away, there’s something about the setting’s intimacy that will draw others in.

And this story is certainly one worth drawing close to.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.