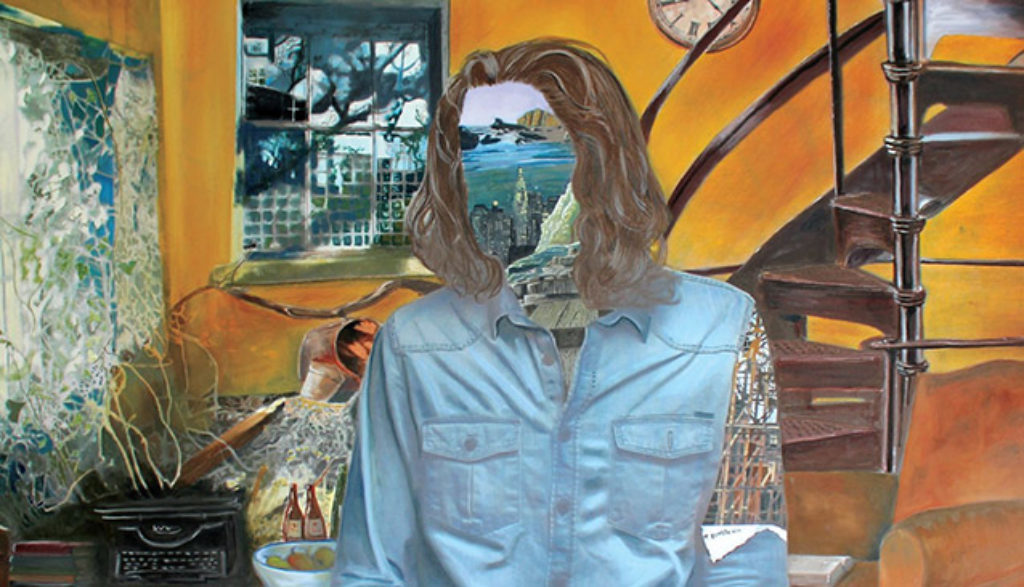

Andrew Hozier-Byrne isn’t very old. But the 23-year-old Irish singer-songwriter, who goes by just Hozier, sounds like he’s lived several times that span.

Perhaps it’s because his diverse musical influences borrow from the better part of the 20th century, including, in his words, “Chicago blues, Texan blues, Chess Records, Motown, and then I discovered jazz, but more importantly, Delta blues—that extraordinarily haunting sound. Skip James, Blind Willie Johnson, people like that. Later, it was Pink Floyd, Nina Simone, Billie Holiday, plus Tom Waits was a huge, huge influence. I was always drawn to singers with something haunting about their voices. The same goes for writers such as James Joyce and Oscar Wilde. You can’t define what it is, but it buries itself deep in your soul.”

If there’s a lot of old in Hozier’s soul, however, one could argue that his perspective on sex and religion is about as up-to-the-minute as it gets. The title of his first single, ” Take Me to Church,” for instance, sounds spiritual. But for Hozier, the worship service he’s interested in attending is something quite different.

“Jackie and Wilson” finds a man briefly daydreaming about having children with a woman he cares for. “Sedated” could be heard as a cautionary tale about a man who’s having a hard time finding meaning in life. Lyrics hint at intravenous drug use (“Just a little rush, babe/ … Our veins are busy, but my heart’s in atrophy”), but there’s also a self-aware critique of a couple’s destructive habits (“You and I are nursing on a poison that never stung/Our teeth and lungs are lined with the scum of it/Somewhere for this, death and guns/We are deaf, we are numb/Free and young, we can feel none of it”). Similarly, Hozier admits he’s enslaved to physical intimacy because it’s as close as he can get to meaning (“So we’re slaves to any semblance of touch/Lord, we should quit, but we love it too much”).

So what’s “church” for Hozier? Sex. “My church offers no absolutes,” he sings on ” Take Me to Church,” “She tells me, ‘Worship in the bedroom’/The only heaven I’ll be sent to/Is when I’m alone with you.” He adds, “No masters or kings/When the ritual begins/There is no sweeter innocence than our gentle sin.” Only in sexual expression, he insists, do we encounter the essence of our humanity (“Only then am I human/Only then am I clean/Amen. Amen. Amen. Amen”). As for Christ’s actual church, well, it’s a place for groveling and deception. He snarls, “Take me to church/I’ll worship like a dog at the shrine of your lies/I’ll tell you my sins and you can sharpen your knife.”

Misuses of God’s and Jesus’ names turn up regularly. “Someone New” asks, “Would things be easier if there was a right way?/Honey, there is no right way,” then repeats, “And so I fall in love just a little ol’ little bit every day with someone new,” followed by, “Love with every stranger, the stranger the better.”

Lovers on “Like Real People Do” agree not to talk about their shady pasts. After a combustible relationship goes up in flames on “Jackie and Wilson,” Hozier ponders when his next bad romance might commence. “Angel of Small Death and the Codeine Scene” finds a man embroiled in a toxic, narcotic-fueled relationship (“Toying somewhere between love and abuse”), yet he’s quite willing to stick around for more (“No shortage of sordid, no protest from me”). There’s more of the same on “Cherry Wine.” And drugs and dysfunction mingle again on “To Be Alone.”

It’s carnal pleasures and images of death that intertwine on “In a Week,” as a tryst on the grass leads to a post-coital nature nap … and then to a permanent one (“We’ll lay here for years or for hours/ … So long we’d become the flowers”). The song ends with the specter of animals making a meal of the deceased lovers. On “It Will Come Back,” Hozier compares a woman taking in a sexually voracious man to someone adopting a ravenous dog.

If you asked me to pick one lyric that succinctly sums up Hozier’s approach to love, life and sex, I’d return with this one: “Honey, there is no right way.” And the result is a worldview that rejects the possibility of goodness and morality. He sings, “Idealism sits in prison, chivalry fell on its sword/Innocence died screaming, honey, ask me, I should know/I slithered here from Eden, just outside your door.”

The only salvation to be found in such a world? Sexual contact, something Hozier goes so far as saying is his religion. Talking with New York Magazine, he commented, “Sexuality, and sexual orientation—regardless of orientation—is just natural. An act of sex is one of the most human things. But an organization like the church, say, through its doctrine, would undermine humanity by successfully teaching shame about sexual orientation—that it is sinful, or that it offends God. The song is about asserting yourself and reclaiming your humanity through an act of love.”

But on “Sedated,” Hozier hints that his hunger for meaning and connection really isn’t being fulfilled in physical connections that leave him unfulfilled and utterly enslaved to pursuing more and more of them.

So is sex with “strangers” slavery or salvation? Hozier’s hoping for the latter, so his music tries desperately to mask the former.

After serving as an associate editor at NavPress’ Discipleship Journal and consulting editor for Current Thoughts and Trends, Adam now oversees the editing and publishing of Plugged In’s reviews as the site’s director. He and his wife, Jennifer, have three children. In their free time, the Holzes enjoy playing games, a variety of musical instruments, swimming and … watching movies.