It’s common to hear musicians, especially rappers, brag that their latest effort is a game-changer. But it’s always a much easier statement to make than to back up. In the case of 27-year-old rapper Kendrick Lamar’s third album, To Pimp a Butterfly, however, game-changer might actually be an understatement.

Butterfly’s 16 songs find Lamar deconstructing all sorts of important relationships: his relationship with himself, his family, his friends and his fans; blacks’ relationship with other blacks, with whites, the police and culture; hip-hop’s relationship with violence, sex and excess. Lamar even delves into his struggles with depression and frames several songs in terms of trying to resist the charms of Lucy—reportedly an abbreviation for Lucifer—and to follow God.

It’s a provocative, unusual and unsettling album, one that’s drenched in honesty and self-critique … and obscene and bitter lyricism.

“Wesley’s Theory” dives into the issue of how successful black artists manage their fame. The song’s title refers to actor Wesley Snipes, who went to jail for tax evasion. And Lamar mentions black celebs medicating with materialism (“Then hit the register and make me feel better, baby”). “King Kunta” (a reference to the famous African-American slave Kunta Kinte) critiques rap’s self-destructive culture (“I was gonna kill a couple of rappers but they did it to themselves/Everybody’s suicidal, they don’t even need my help”). “Institutionalized” explores Lamar’s sense of being constrained by different aspects of his culture (“I’m trapped inside the ghetto, and I ain’t proud to admit it/Institutionalized, I keep running back for a visit”).

“Complexion (A Zulu Love)” counsels looking past skin color. “The Blacker the Berry” laments the troubled interactions of police officers and blacks, as well as black-on-black violence (“So why did I weep when Trayvon Martion was in the street?/When gangbanging make me kill a n-gga blacker than me?/Hypocrite!”). Intra-black violence also turns up on “i,” where Lamar talks more about his struggles with depression. A wince-inducing self-assessment of the artist’s own failures springs from “u,” as Kendrick laments not visiting a friend in the hospital who was wounded in a shootout. “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Momma Said)” tells listeners they don’t have to exaggerate stories about themselves to prove their worth. “Momma” suggests the ultimate place of security is home, where our family tells us, “We been waitin’ for you.” Home is also deemed a place of self-knowledge (“I know everything, know myself/I know morality, spirituality, good and bad health”). “Hood Politics” challenges rival gangs to set aside their animosity.

“Alright” says, “But if God got us/Then we gon’ be alright.” That song and “For Sale?” both reference resisting the temptations of the devil, dubbed Lucy. “How Much a Dollar Cost” is a complex rap about Lamar not wanting to give a homeless man money at a gas station. Then, in a twist at the end, we learn that the homeless man was actually Jesus (“He looked at me and said, ‘Know the truth, it’ll set you free/You’re lookin’ at the Messiah, the son of Jehovah, the higher power/The choir that spoke the Word, the Holy Spirit, the nerve/Of Nazareth, and I’ll tell you just how much a dollar cost/The price of having a spot in heaven, embrace your loss, I am God'”).

The album concludes with the 12-minute opus “Mortal.” In it, Lamar finalizes a lengthy confessional (that’s initiated in previous songs, each time with more autobiographical details added to this spoken-word segment): “I remember you was conflicted. Misusing your influence. Sometimes I did the same. Abusing my power, full of resentment. Resentment that had turned into a deep depression. Found myself screaming in the hotel room. I didn’t wanna self-destruct. The evils of Lucy was all around me. So I went running for answers. Until I came home.” He goes on to criticize black-on-black violence once more (“Just because you wore a different gang color than mine’s/Doesn’t mean I can’t respect you as a black man/Forgetting all the pain and hurt we caused each other in these streets/If I respect you, we unify and stop the enemy from killing us”).

A flood of f-words (frequently paired with “mother”), s-words and myriad instances of “n-gga” mar virtually every track. Graphic references to male and female genitalia are spit out, as well as allusions to oral and anal sex. We hear the sounds of a woman’s orgasm. On “Wesley’s Theory,” Lamar raps, “At first I did love you/But now I just wanna f—/Late nights thinkin’ of you/Until I got my nut.” “These Walls” is an extended metaphor for a woman’s anatomy.

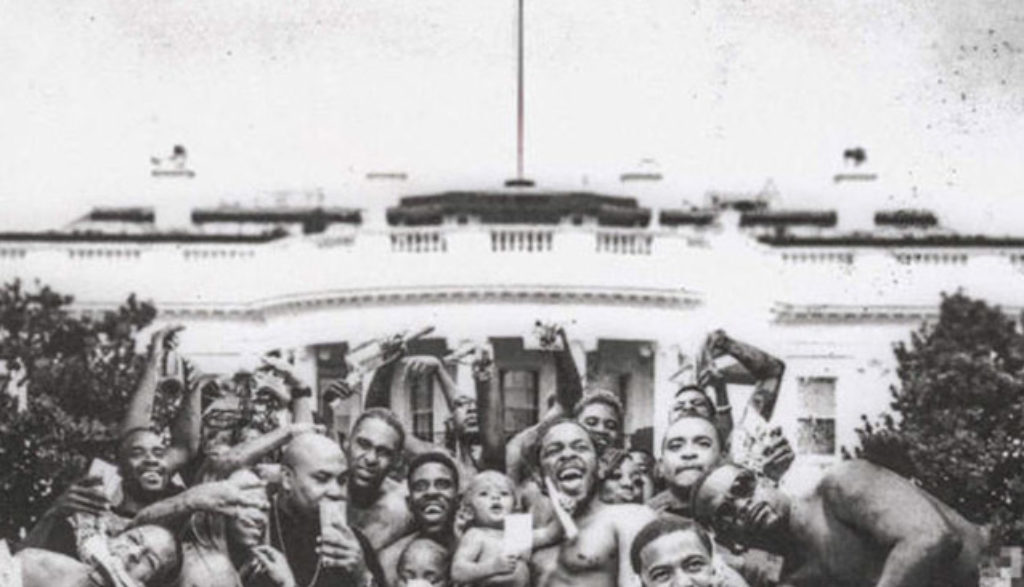

“Institutionalized” fantasizes about getting high at the White House. Songs repeatedly and heatedly criticize the police, judges and a legal system Lamar says is rigged against blacks. So for all the talk of peace and reconciliation within the black community, at times it doesn’t seem as if the same courtesy is extended to whites or those in power. “The Blacker the Berry” accuses, “You hate me, don’t you?/You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture/You’re f—in’ evil/I want you to recognize that I’m a proud monkey.” Similarly, a repeated line on “i” could be heard as inciting fans to murder police officers (“Ahh, I put a bullet in the back of the back of the head of the police”). Worse, that line is quickly followed by another suggesting that such violence could be God’s idea (“Illuminated by the hand of God, boy don’t seem shy”). In similar territory, an imported recording of deceased rapper Tupac Shakur (on “Mortal”) has him saying blacks and whites are destined to fight it out in a winner-take-all race war (“I think that n-ggas is tired of grabbin’ s— out the stores, and next time it’s a riot there’s gonna be, like, uh, bloodshed for real. I don’t think America know that”).

To Pimp a Butterfly captures scores of self-aware, self-critical observations as Kendrick Lamar dissects his own life, the rap world directly surrounding him and certain aspects of black culture at large. That kind of psychosocial and emotional exercise can be beneficial, to say the least. But these thought-provoking moments are often saturated with obscenities, explicit sexual imagery and (occasionally) violent hostility toward the mainstream culture. And that cripples the influence Kendrick Lamar was obviously hoping to have.

After serving as an associate editor at NavPress’ Discipleship Journal and consulting editor for Current Thoughts and Trends, Adam now oversees the editing and publishing of Plugged In’s reviews as the site’s director. He and his wife, Jennifer, have three children. In their free time, the Holzes enjoy playing games, a variety of musical instruments, swimming and … watching movies.