Alcaeus and Amphitryon do not have an ideal father-son relationship.

Does Amphitryon ever take Alcaeus out and throw the ol’ pig around? Go down to the city to watch the chariot races? No. The glowering guy with the intimidating beard—who just so happens to be the king of Tiryns—always favored eldest son Iphicles, giving him everything he could want and forbidding anyone to make fun of his goofy name.

Not that Alcaeus is bitter. He has his muscles to keep him company. And should he tire of them, he can always hang out with Hebe, the beautiful daughter of another powerful Greek king. They’re in love—the sort of true, unquenchable love that hair bands from the 1980s used to sing about. Nothing but nothing will tear them apart.

Alas, every rose has its thorn. One night after Alcaeus and Hebe have spent some time languishing in a pool, and he and Iphicles have killed the fearsome Numean lion (ancient Greece was a hoppin’ place), Amphitryon makes an important announcement: Iphicles and Hebe are to be married four moons hence and (surely stifling evil laughter) Alcaeus is to be sent to Egypt to quell some sort of revolt that he may or may not have just made up. In one fell swoop, the king has cemented an important alliance and ticked off his second son. Or maybe it’d be easier to just say he gives love a bad name.

On his way out the door, Alcaeus runs into his mother, Queen Alcmene, who has some startling news for her favorite son: His name isn’t really Alcaeus at all, but Hercules—or sometimes Heracles, depending on who’s saying it. And his father isn’t Amphitryon, but Zeus, king of all Grecian gods.

It’s the sort of announcement that’s bound to throw anyone’s life into uncertainty, and I’m guessing sparked many, many questions in young Herc—most of which we can only guess at, you know, this many centuries after something that didn’t actually happen. I’m the son of a god? Is this why I have all these muscles? Why I’ve never been able to grow a huge beard? So it was me that mother was talking to at the dinner table when she’d say, “Hercules, please pass the beets”? Iphicles falls in a forest and there’s no one to hear it, will he still marry Hebe?

Firstly, The Legend of Hercules gave me a new appreciation for the Disney cartoon Hercules—which, by comparison, seems like a deep and sober study of Greek mythology. But I guess I can come up with something nice to say about this flick: Hercules, for instance, seems like a nice enough guy. When he and Iphicles face the Numean lion, he tries to get his sibling to flee to safety. And when Herc kills the beast, he at first allows his insecure elder bro to take most of the credit. (Iphicles, naturally, makes himself more of a jerk in the process, which just shows you what an Iphy guy he is.) Hercules saves or tries to save the lives of some other folks too.

Hercules’ good pal Sotiris loves his wife and kid. Hebe shows some self-sacrificial tendencies that she uses to save her muscular man. Some guy keeps Hebe from walking off a high wall. (Nice of him, that.)

The Legend of Hercules is predicated on a supernatural union and never shies away from religious issues—usually talking about them in strange surfacy ways, but sometimes in ways that might actually trigger some deeper thoughts. Indeed, if the main purpose of the movie is to showcase Hercules smiting folks, the secondary message is about how critical it is to have faith.

Remember always, of course, that the faith in play here is that of the ancient Greeks and their pantheon of petty gods. Queen Alcmene serves the goddess Hera (Zeus’ wife), for instance, and when Amphitryon (a rare Grecian atheist) mocks her for her beliefs, she’s not dissuaded. Her faith is then “rewarded” when Hera strikes a bargain with her: She (Hera) will allow Zeus to sleep with Alcmene and create a future savior for her country—someone who will give the land peace. Alcmene says that sounds dandy.

(This, by the way, runs completely counter to the generally accepted Grecian myth, wherein Hera can’t stand Hercules and does everything she can to kill the guy.)

But when Alcmene tells Hercules about his lineage, her son thinks she’s outright crazy. He’s a skeptic, not only about his own demigod status, but about gods in general. When a soldier sees an eagle flying overhead and says that such birds are thought to be a sign from Zeus, Hercules says, “Yes, and some believe it’s just a bird.” And when someone talks about how Zeus has a plan for him, Hercules thunders, “Where was this father when 80 good men were murdered beside me?!” It’s not until a moment of crisis that Hercules experiences a come-to-Zeus moment—turning the whole sometimes silly thing into something of a twisted Christian allegory.

There are hints of this throughout, actually. Hercules, Alcmene believes, is a true savior for the land. She and others often talk about his god-given purpose. His lineage seems intended to echo Jesus’ own status as being both God and man. When Hercules is captured (betrayed by one of his friends), he’s strung up in a temple and scourged mercilessly. Amphitryon, the unbeliever, chastises the horrified masses watching the beating for believing in him: He’s flesh and blood, he rages—not a god at all. “Is this a message of hope?” he thunders. “Self-proclaimed son of Zeus,” he says, turning his attention to Hercules. “How do you offer these people salvation when you cannot save yourself?”

And then Hercules slides the picture away from Jesus and toward Sampson. “I believe in you,” he tells his unseen father. “Grant me strength,” as he pulls down the pillars he’s been chained to.

His next move? Well, he thinks, What would Hercules do? And so he starts twirling the pillars’ stones—still chained to his wrists—mowing down his accusers left and right. The filmmakers may have wanted to make him a Christ-like metaphor, but this “savior” isn’t about to turn the other cheek.

Hercules and Hebe are quite affectionate with each other. We see them swim half-clothed and smooch under waterfalls. Amphitryon asks, for Iphicles’ sake, whether Hercules claimed Hebe’s “maidenhead.” “It’s none of your business,” Hercules answers. Indeed, later the two share an intimate encounter in a makeshift hideaway, both wrapped in sheets to cover strategic regions of their bare bodies. Hercules lies on top of Hebe, and the side of Hebe’s breast is briefly visible.

Alcmene’s encounter with Zeus, meanwhile, involves her lying in bed while Zeus takes the form of a strong breeze, blowing under her covers and giving (it would seem) the nightgown-wearing queen sexual pleasure. She climaxes just as Amphitryon storms in, seeing that his wife’s been involved in some hanky-panky with someone.

Hercules, Amphitryon and others go shirtless, and the movie obviously wants to draw as much attention as possible to their physiques. (Where’s Taylor Lautner when a director needs him?) Women wear gauzy gowns that sometimes show off cleavage.

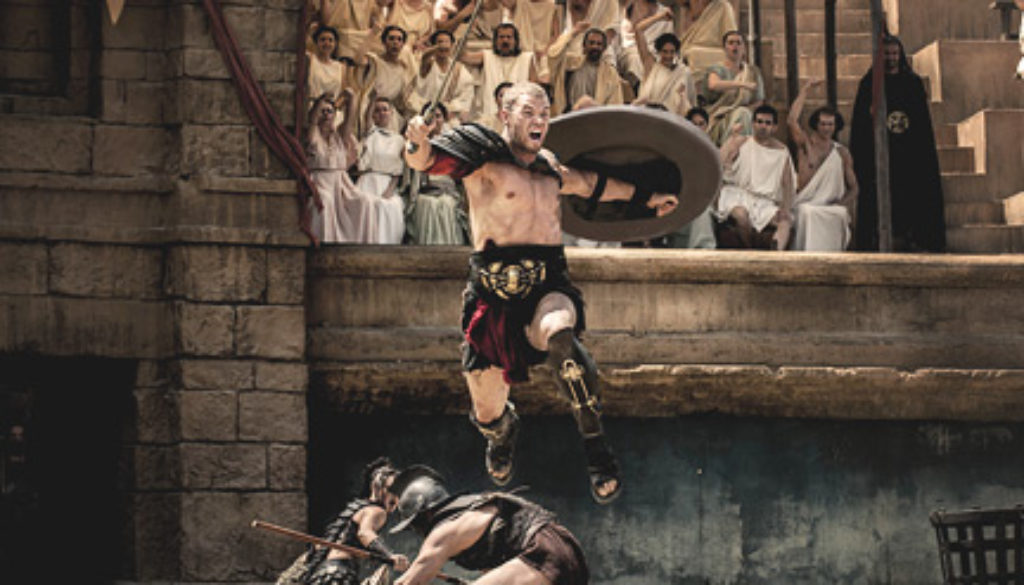

The Legend of Hercules aspires to be a PG-13 version of 300, it would seem—little more than an excuse to string never-ending, highly stylized fight sequences together. In wartime skirmishes and gladiatorial contests, men are dispatched with swords, cudgels and arrows. Women are hit, thrown around and occasionally stabbed. Folks fall into pits full of spears. We see dead bodies hanging from ropes and lots of bloody corpses strewn around on the ground, sometimes with arrows sticking out of them. Arms and necks are broken. (We hear the crunches.) Someone affixes someone else’s foot to an arena floor with a shield (somehow). People are drowned. They’re bashed by flying pillar stones. Soldiers are electrocuted with a magical sword/whip infused with lightning. We sometimes hear screaming and see splashes of blood. We watch what looks like a decapitation (but isn’t).

Hercules and Sotiris are painfully branded. Hercules gets shot by several arrows during a battle (but the arrows just sort of vanish as the melee drags on and he refuses to die). During a contest, Sotiris is punctured in both the arm and leg, leaving wounds that look pretty painful.

A woman nearly kills herself by trying to fall to her death. Later, that same woman runs herself through with a knife to save someone else: The blade comes through her chest and back and skewers the man behind her, killing him. (She, oddly, survives). Another woman gets murdered but is said to have committed suicide.

People are sold into slavery. There’s talk of gladiators becoming piles of “blood and guts and bones” eaten by dogs. A lion, impervious to spear attack, dies via strangulation and a broken neck.

None. (Cursing was apparently not one of the many problems those ancient Greeks had.)

None. (Drinking was certainly one of those problems, but the movie’s too consumed with fighting to take the time to show it.)

Despite everything I was pondering in “Spiritual Content” above, attempting to bring some sort of Christian meaning to a tale of Greek gods only goes so far, even in Hollywood. And when both myth and metaphor are stuffed into a low-budget action flick meant for bored 13-year-old boys, things get even funkier. It’s hard, after all, to mull over the nature and divinity of Jesus when the movie’s “Christ figure” is thwacking his jackal-helmeted enemies with two-ton stones while screaming at the top of his lungs.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.