We live in an increasingly secular age. Fewer people go to church. Atheists are on the rise. Ideas of heaven and hell are seen by many as a bit anachronistic.

Which makes the occasional case of demon possession a bit prickly.

Luckily for those people, Dr. Seth Ember has their backs.

Ember is an exorcist—er, malignant spirit evacuation specialist. Holy water and crosses are for suckers, he believes. He uses science to boot those pesky demons—er, malignant spirits, from their poor human hosts. He dives into their subconsciouses, mucking around in their waking dreams and figuring out a way to pull the poor unfortunate souls—er, minds, back into a state of consciousness. Once that happens, the spirit has no power and promptly dies.

Yay science! It does have an answer for everything.

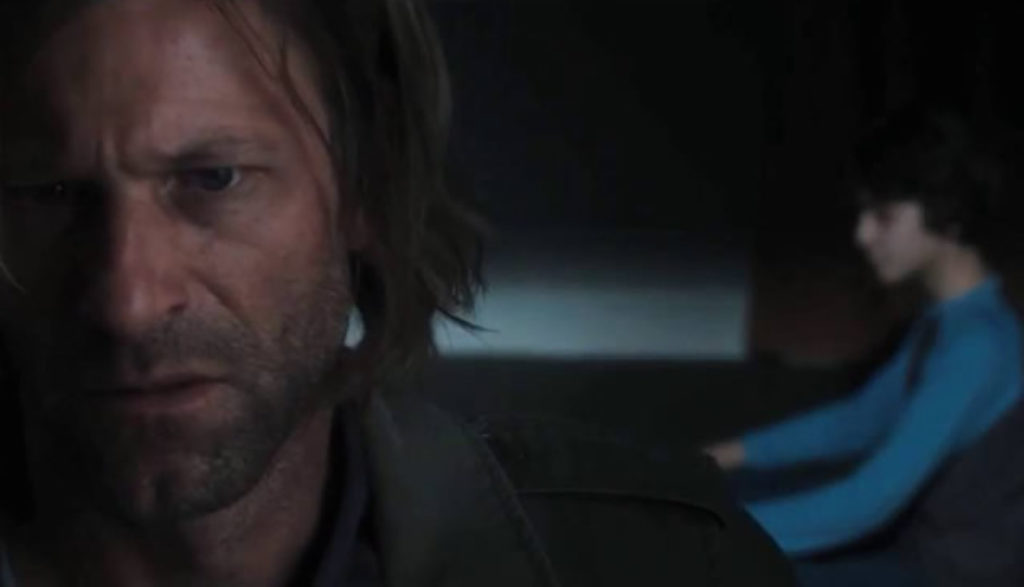

But from Ember’s scruffy, bedraggled garb, to his tendency to drink, to his perpetually crabby demeanor, we know the guy is possessed by his own metaphorical demons. And he’s also haunted by a very literal one: an evil spirit who goes by Maggie, whom Ember has been seeking for ever so long. Seems he holds a grudge against the entity for killing his wife and kid. Or maybe she holds a grudge against him. It’s difficult to tell. But whatever the case is, they’re certainly not on each other’s non-denominational holiday card list.

Ember had despaired of ever tracking Maggie down … until Camilla, a beautiful representative from the Vatican, stops by for a chat. She tells Ember that an arch-demon (Camilla’s Catholic, so she can use such language) is loitering in the body of a 10-year-old boy named Cameron, biding her time until she can make a leap to a new host. The Vatican suspects that the demon may be Maggie. But even though the Catholic Church sent in its best exorcists, Camilla admits they’ve been “ineffective.”

Ember isn’t happy to be working with the Vatican. But having a chance to deal with Maggie is too much of a draw. He’ll take the case, take out Maggie and rescue the boy.

If he can.

He knows it won’t be easy. Maggie is, after all, an arch-de—er, very powerful spirit. And lately the dream states he enters have felt all too real, leaving him potentially under a given spirit’s influence. Is it possible that this could be Ember’s last case? Is it possible that he could finally meet his ecumenical maker(s)? Or might Maggie claim him for her own?

A Christian conception of heaven and hell may not be in play in this story, but Ember believes this: There are still some fates worse than death.

Whatever Ember’s belief system might be, it is good of him to save people from their demons. Even though he primarily does his work in order to find and fight malignant entities, he is happy to help people along the way. When Cameron’s mother questions his rough, self-centered approach—that he’s just there to take down Maggie and doesn’t care about the boy—Ember admits that he does care.

Before he’s possessed by Maggie, Cameron seems to be a nice, thoughtful lad. He picks up his mother’s keys when she drops them. He covers his mother with a blanket when she falls asleep on the couch. Certainly he deserves better than having his body hijacked by a malicious spirit.

“I just don’t think that what I do belongs to any one religion,” Ember tells Camilla. What one faith calls a demon, he says, another might call an unclean spirit or a djinn. They’re all the same to him: disembodied beings that latch onto humans, take them over and eventually kill them. Both he and Maggie demean the traditional trappings of exorcism (“Holy water, crucifixes … get so dull,” she says).

But it’s hard to tell a possession story without invoking various religious tropes and images. Both Ember and Maggie reference places that sound like hell. Ember refers to spirits as “succubi.”

And when he goes to deal with Maggie, he puts a cross around his neck—one that was always worn by his wife.

Ember often lambasts Catholic representatives for their supposedly brutal exorcism techniques. (He insinuates that many people die as a result of their exorcisms.) One Catholic priest, Felix, keeps a possessed man in captivity. Frightening metal instruments lie nearby, suggesting that Felix is torturing the spirit (and, of course, its mortal host) in order to extract information from a malignant netherworld.

Wicked spirits unleash a lot of mischief. Their favorite trick seems to be levitating human hosts or victims in mid-air, sometimes plastering them against ceilings.

One of Ember’s exorcism clients is trapped in a waking dream that takes place in a seedy nightclub, and he’s surrounded by beautiful women in tight, sometimes cleavage-baring clothes. We learn later that the victim sometimes visited strip clubs.

Ember finds Cameron’s father in a bar, grabbing a flirty woman’s breasts and tugging on her jeans’ waistband. Elsewhere, we see a couple kiss.

People fall from ceilings or windows, sometimes dying. One woman, her face mottled and torn, has her neck broken following Maggie’s possession. A man, inhabited by a demon, slits his own throat (off-camera).

Ember chokes a possessed man until he agrees to do what Ember tells him to do. In a dream state, Ember begins to bleed from the abdomen, eventually coughing up blood as he lies down, apparently dying. A man comes to supposedly help him, then turns demonic and shoves his hand into Ember’s abdomen. (We only get a split-second glimpse of this cavity invasion before the scene switches.) Ember gets into fights with various spirit entities in these dream worlds: Sometimes they beat each other. Ember psychically sets one afire. In order for victims to be jarred loose from their dreams, they must always jump from high windows. Maggie tells Ember she intends to “torture all you love.”

We hear several times that Cameron’s father broke the boy’s arm. On a voice mail message, the man insists, “I didn’t mean to hit him!”

In flashback, we see the car accident that claimed the lives of Ember’s wife and son. A car hits their vehicle head-on, and Ember sees his wife’s body, her face bloodied, smashed on the car’s dashboard. His son’s body lies outside, a nearby curb stained with blood. Ember also sees the driver of the other car—who’s also clearly bloodied and seemingly dead— then reanimate.

[Spoiler Warning] In order to dive into a possession victim’s unconsciousness, Ember and his team must bring him to a state of near death via a chemical IV. Knowing that Maggie poses a threat worse than death, Ember hooks up what seems to be a suicide drug—something that as a last resort will kill him and will keep his soul from falling into Maggie’s clutches.

One f-word, half a dozen s-words and a moderate dusting of other profanities, including “a–,” “b–ch,” “d–n” and “h—.” God’s name is misused six times, and Jesus’ name is abused about half that many.

Ember and Felix have drinks together (whiskey and wine, respectively). Ember swigs from a flask, and he goes into a bar to fetch Cameron’s father. (The man refuses to leave unless Ember buys him another beer.) People drink in a club.

Someone coughs up a dark, oily substance after being freed of spirit possession.

There are certain things that should not be done.

For instance, one should not make Thanksgiving stuffing without gluten. Gluten-free stuffing tastes like gravel and Kleenex. Likewise, one should not make cars without tires; make superhero movies wherein the superheroes spend the entire film watching football. These things are, to me, self-evident.

Here’s another: One should not make an exorcism movie without God and faith in the mix.

Secular horror meisters find themselves in a difficult position these days. Stories depicting demonic possession are powerful stories, scary stories and—perhaps most importantly to Hollywood bean counters—stories that make money.

But these practitioners of onscreen terror can read the religious trends as much as we can. Young people—the folks who largely make up the horror audience—are more secular than their parents or grandparents. They’re less likely to believe in anything. So is it possible to make an effective exorcism story without, y’know, all that God stuff?

No. And Incarnate proves it. Its makers tried. They did their best to exorcise religion from the story and create some quasi-mystical, pseudo-scientific underpinning. But the evil spirits still recited strange, spell-like incantations and acted for all the world just like traditional demons. And when it came time for a resonant climax, a demon hunter in all but name still stuffs a crucifix down his enemy’s throat.

Whatever your thoughts are about horror in general, supernatural frights are dependent upon a supernatural faith and worldview. We have to believe in God to tell stories about the devil. Uncoupling the two just doesn’t work. And not just from the perspective of faith, but from the perspective of good storytelling, too. To try to do so leaves us with … well, the cinematic equivalent of gluten-free stuffing.

Despite its secular underpinnings, this movie, frankly, isn’t good enough or strong enough to challenge very many people’s faith. The content we see here isn’t extreme, by horror movie standards. Cups of blood are spilled, not gallons. Gore is minimal. Jump scenes are sparse and, for the most part, ineffective.

But that doesn’t make this religion-free demon possession movie worth seeing.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.