Frank Lucas likes to think of himself as just a plain ol’ businessman—an entrepreneur filling a free-market niche. He buys his product direct, cuts out the middleman and passes the savings on to his customers: His product is twice as good at half the price.

Only one problem: His product is heroin.

Frank doesn’t use the stuff himself, of course. For him, it’s just a conduit to an outsized American Dream—one that allows him to buy a house for his mother, take care of his family and get great seats at championship boxing matches. More than anything, though, Frank craves respect, just as much as his customers crave the “Blue Magic” he sells. And in 1970s New York, there’s little to stop a motivated hustler like Frank from making a buck. The police don’t want to put guys like him away—they just want part of the cut. Right?

The exception is Richie Roberts, a flawed cop with an honest streak. He’s been tapped to head a New Jersey vice squad to crack down on the region’s biggest drug dealers. At first, he figures he’ll have to tackle the mafia to do it.

But then Richie sees Frank stride into Madison Square Garden for a premiere boxing event with a chinchilla coat and ringside tickets—better than the city’s known Italian crime lords. It looks like New York’s found a new don.

Richie’s a bit messed up, but when it comes to doing his job, the cop’s a straight arrow. When he and his partner find $1 million in dirty money stashed in the back of a car, they could easily pocket it. His partner argues that, if they don’t take it, they’ll become pariahs among their cash-skimming colleagues.

“Cops kill cops they can’t trust,” Richie’s partner says. “We can’t turn it in, man.”

But Richie is, in his police work, incorruptible. When his partner asks him to lie on a police report to save his skin, Richie refuses. When a mobster offers him a bribe to lay off Frank, Richie walks away. When a rival dirty cop tells him that they need to help keep Frank in business to keep the graft flowing, Richie informs him that the police he works with do things a little differently.

“You know what we do here?” Richie says. “Cops arrest bad guys.”

During a messy custody hearing, though, Richie’s ex-wife tells him that his vaunted honesty is really nothing more than an excuse for him to be “dishonest about everything else.”

The words hit home, and Richie’s actions reflect an integrity that’s used by the filmmakers to contrast the self-deception Frank engages in. “What matters in business is honesty, integrity, hard work, loyalty and never forgetting where you came from,” Frank tells his brothers. And he’s convinced his “brand” stands for something, getting mad at other drug dealers when they dilute his product and pass it off as his. But despite the fact that he loves his mother and does nice things for her—including taking her to church—this is a guy who kills people and sells drugs, not toasters, whether or not he’s willing to admit it to himself.

Frank is a churchgoer, and his marriage takes place in the church. He says a prayer during Thanksgiving dinner, asking God to “feed our souls with heavenly grace.” As we hear Frank pray the scene shifts to horrific images of drug addicts shooting up, shivering, even overdosing.

[Spoiler Warning] Frank is arrested outside the church as the congregation inside sings “Amazing Grace.” And we see the rest of the Lucas clan getting busted and handcuffed during the same tune. It is, perhaps, a bit of foreshadowing, since because of a plea bargain, Frank ends up partnering with Richie to rid the police of corruption. Once their task is completed, Richie asks Frank whether he wants something to drink to celebrate. “You got any holy water?” Frank asks.

Nude and nearly nude women populate Frank’s drug “factory,” where pure heroin is packaged for the street. They’re naked, Frank explains, so they don’t steal any of the product. They slowly dance and writhe as they work, and audiences see everything—in several scenes. Three naked women give a man a rubdown. Women in skimpy clothing—presumably prostitutes—appear frequently, sometimes loitering on street corners or apartment buildings, sometimes dancing in Bangkok bars. One of Frank’s party guests is shown squeezing the breast of another guest.

Richie is a womanizer. He’s shown having sex with his lawyer, her uncovered legs wrapped around his waist as they noisily pant and bounce around his kitchen. He also shares a passionate kiss with a stewardess. Some of his vice squad workers are shown in a nightclub, one gyrating passionately between two rotund female dancers, another dancing suggestively with a blond woman.

Frank deals death just as freely as he deal drugs. American Gangster opens with him participating in a man’s torture and death. The victim, whose shirt is bloody, is doused with gasoline and set on fire before Frank shoots him several times.

The gangster’s just getting warmed up. In flashback mode, we see Frank shoot a guy in the head while the man’s sitting on a bed, his blood spattering against a window. Frank walks out of a breakfast meeting to shoot a rival point-blank in the forehead, and we see the corpse lying in a pool of blood, the bullet wound clearly visible.

Frank’s non-lethal attacks are, oddly, even more painful to watch: When one of his cousins shoots a party guest in the leg (we see the shot fired and blood fly), Frank punches the cousin and then repeatedly slams his head with a piano lid. In another scene, he bashes his brother’s head repeatedly into a car window, shattering the latter and rendering the former unconscious.

He also blows up a police officer’s prized Ford Mustang.

As for the cops, when dirty ones raid Frank’s house, Frank’s wife gets slapped across the face and a guard dog takes a bullet. One fight includes biting and door smashing. One police officer commits suicide by shooting himself in the head; blood spatters.

Another bloody body is seen lying dead on a floor. Thugs pound someone with a pool cue and push someone else down a flight of stairs. Unnamed assailants try to kill Frank’s wife, peppering their car with bullets.

And all of this is just a prelude to Richie’s raid on Frank’s drug factory, where bullets blacken the field of vision and blood collects on the ground.

No fewer than 125 f-words. The s-word clocks in between 20 and 30. God’s name is misused (most often paired with “d–n”) more than a half-dozen times. Offensive racial epithets are hurled, as are vulgar names for sexual body parts.

Just because a movie is about a drug dealer doesn’t mean it always shows people using the merchandise. But that’s not how American Gangster plays it. Here we see a lot of folks sticking needles—sometimes broken—into various parts of their bodies. They shake and sweat, shown to be nearly animals, prey to their own seemingly uncontrollable cravings. A few die of overdose. One, a young mother, lies lifeless on a bed as her child cries beside her.

Some peripheral characters are shown snorting cocaine, too. Frank gets angry with one of his cousins for always being “coked up.” While Frank is never shown indulging, others use it openly around him, even at his parties.

It should go without saying, then, that we also see characters drink and smoke with abandon. Frank often smokes a cigar. Richie downs whiskey. Etcetera.

Richie was apparently an inattentive husband and is now an inattentive father—aspects of his character, it’s suggested, that led to his divorce.

Richie and his partner break into a suspect’s car without a warrant (it was apparently on its way), but that’s a minor infraction compared to what seems like an entire department of crooked cops who view the job as an opportunity to get rich, not do good.

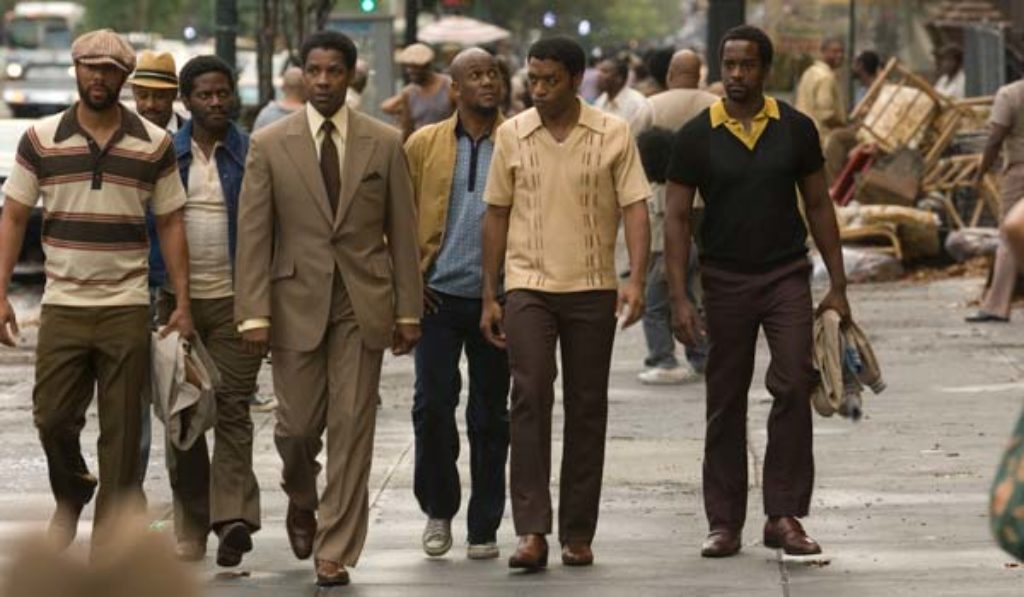

American Gangster is based on the real life of Frank Lucas, who spent 15 years behind bars. But Denzel Washington’s Frank seems to be a far cry from the real deal: Onscreen, Frank is erudite, mannered and reasonably reserved. Real-life Lucas claims, in a 2005 New York Magazine story, that he never went to school even for a day and owned 100 garish, custom-made suits. Forget the principles Frank spews in the film, Lucas says he was in it for the money.

One thing they share, though. They’re very likeable characters.

“People like me,” Lucas told New York Magazine. “People like the f— out of me.”

Indeed. During a family get-together in the film, Frank sits down with a young cousin of his—a natural athlete with a 95-mile-an-hour fastball—and asks him why he didn’t attend a tryout with the New York Yankees that he set up for him. The cousin tells him that he doesn’t want to be a ball player anymore.

“I want to be you,” he says.

And that’s just the problem inherent with films like American Gangster. Frank, played with a ferocious dignity that could only be delivered by Washington, is a character folks want to be like. He’s rebel cool, and the hero worship began even before the film was released: On his upcoming album called (surprise!) American Gangster, rapper Jay-Z stresses the similarities between himself and Frank. His song “No Hook” reportedly contains the line, “Please don’t compare me to other rappers/Compare me to trappers/I’m more Frank Lucas than Ludacris.”

Such is life. If being bad wasn’t appealing, nobody would be. American Gangster tries to remind us that Frank is spreading a huge evil—its depictions of heroin users are tragic. What it ends up doing, though, is allowing evil to seduce through this character.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.