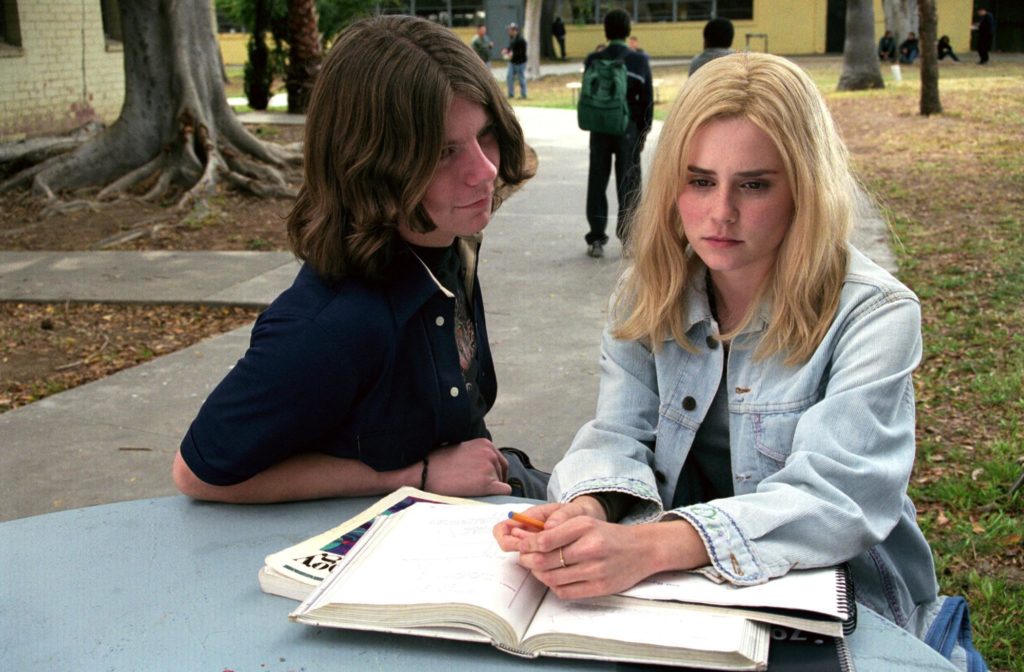

Based on Janet Finch’s best-selling novel, White Oleander loses itself in one girl’s desperate journey through adolescence, foster homes and abuse. Astrid is only 15 when her brilliant, artistic, passionate, inflexible mom is arrested for killing her cheating lover. Set adrift and solely reliant on Los Angeles’ social services, Astrid learns fast that just because a foster parent picks her doesn’t mean she’s going to be loved. The three foster home experiences fall into the categories of bad, worse and awful. One mom kills herself. Another physically abuses her. A third puts her to work scavenging through garbage cans for saleable clothes and merchandise. Through it all, the only constant thing in Astrid’s life is the formidable presence of her imprisoned mother. Even behind bars, Ingrid’s defiant and pride-tainted love is fierce and far-reaching. A slow interplay of dependence, disinterest, trust, hate and wariness ensues.

positive elements: It’s not often that a film so clearly delineates the secondary effects of one’s decisions and actions. When Ingrid murders her boyfriend, she’s consumed with thoughts of her own well-being, but she completely disregards her daughter’s. That’s disastrous for Astrid. Much of the film is devoted to showing what Ingrid’s actions do to her daughter. Astrid’s loneliness and pain is made abundantly clear as she clings to her own delicate sense of self-worth and identity. Instructed by her mom to keep everyone at arms’ length to avoid insult and injury, Astrid rises above the callous advice, realizing that even though people can indeed hurt you cruelly, isolating yourself inflicts wounds of equal severity. [Spoiler Warning] Ingrid ultimately realizes the damage she’s done to her daughter and sacrificially offers up her own destiny for Astrid’s happiness.

spiritual content: The first foster home Astrid finds herself in is headed by Starr, a loud-talking, body-flaunting, alcohol-swilling, cigarette-smoking, gun-wielding, scripture-quoting “Christian.” One of the very first things Starr asks Astrid is if she has “accepted Jesus Christ as [her] personal Savior.” One day later, she lectures on the pervasiveness of sin. “Sin is a virus,” she says, “infecting the whole country like the clap.” Then she quotes John 11:25: “He that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.” At first Astrid gravitates toward the forgiveness promised if she believes in Christ (she’s even baptized), but her experience with “Christianity” is far from Christ-honoring. Beyond eldest daughter Carolee’s pronouncement that the only thing their preacher is interested in is “looking at [Mom’s] a–,” it turns out that Starr is living with a man who is married to another woman. She���s prone to fits of rage and jealousy, drunkenness, meanness and vengeance. All of that gives credence to Ingrid’s bitterness against the Almighty. “If there is a God,” she rants to Astrid, “He sure ain’t worth praying to. I raised you, not a bunch of Bible-thumping trailer trash. I raised you to think for yourself.” When Astrid broaches the subject of “evil” with her mother, Ingrid scoffs, “If thinking for yourself is evil, then every artist is evil. Is that what you believe, now that you’ve been washed in the blood of the lamb?” Astrid responds, “We pray for your redemption every Sunday.” Ingrid yelps back, “F— my redemption. I don’t want to be redeemed. I regret nothing.”

While speaking from a Mormon perspective, science fiction/fantasy author Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Game) aptly describes the way much of Hollywood and the entertainment elite view Christian and religious characters. He says, “In our culture, intellectuals have become so uniformly a-religious or anti-religious that our fiction, with few exceptions, depicts religious people in only two ways: the followers are ignorant and stupid and easily fooled, and the leaders are exploitative and cynical, manipulating others’ faith for their private benefit. I know people who fit those descriptions. But they are in a tiny minority. Most religious people I know are smart, well-educated, independent-minded, stubborn, honest and generous—at least as much so as the average intellectual, and usually more.” White Oleander lives well up to Card’s pronouncements, and it does a flippant disservice to “stubborn, honest and generous” people of faith everywhere.

There is also a short discussion about astrology and the signs of the zodiac.

sexual content: Starr and her boyfriend, Ray, go at it hot and heavy in the next room (the sounds of their activities waft effortlessly through the home’s paper-thin walls. Starr takes Astrid and Carolee shopping, where the cameras follow them into the dressing room (all three are seen in their underwear; Starr is wearing thong panties). She also makes a couple of crude comments about breasts and tells the girls that she used to be a stripper. Worse than that, though, are subtle, unsubstantiated implications that Astrid and Ray are having an affair (whether they are or not, Starr thinks they are). Low-cut blouses and skimpy negligees appear several times on various women. There are jokes about sexual assault in prison. It’s clear that Ingrid was having a sexual relationship with her boyfriend. And while Ingrid admits to loving Astrid’s father, he too was a short fling for her.

violent content: A flashback (shown twice) briefly details a violent confrontation between Ingrid and her boyfriend before she kills him, presumably by poisoning him with white oleander. [Spoiler Warning] In a fit of rage, Starr shoots Astrid in the shoulder. Earlier, she’s heard slapping her daughter (onscreen, when she tries to do it again, Carolee grips her arm and threatens her with harm. A brawl at a group home leads to a black eye and bleeding lip for Astrid. To protect herself from further assault, she puts a knife to one girl’s throat, threatening to slit it if she is touched again. A woman commits suicide by taking pills. Desperate, lonely and enraged, Astrid overturns furniture. A scene from Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre shows a woman about to be ripped apart with the titular tool.

crude or profane language: One f-word and two s-words. The Lord’s name is abused more than a dozen times. Milder profanity and crudities include “h—,” “d–n,” “b–ch,” “screw” and “a–.”

drug and alcohol content: Ingrid, Starr and others routinely smoke cigarettes. At one of the foster homes, the fridge is stocked with beer, and seemingly no one is barred from imbibing. The mother in that same home offers her teenage girls cigarettes. The woman who kills herself gets drunk before taking the pills. There is also talk of Ingrid driving to Tijuana to buy a drug called DMSO, a teen boy who was born addicted to heroin because of his mother’s habit, and Starr’s cocaine abuse.

conclusion: White Oleander is a sad and sobering movie. Its depiction of the potential horrors of foster care and “the system” is enough to make you want to rush right out and draw up a new will to doubly protect your children from such a fate. It also makes you think long and hard about how your own decisions will affect loved ones. “Love humiliates you. Hatred cradles you,” Ingrid tells her daughter. But Astrid discovers that not to be true. “Those people are not the enemy, Mother. We are. They don’t hurt us. We hurt them.” It’s a moment of truth and self-awareness. Astrid realizes how important one’s decisions are and how they affect not only yourself but everyone around you.

Balancing the value found in Astrid’s journey with the damage inflicted by the filmmakers’ reckless portrayal of Christians is difficult. If it were possible to isolate Starr from the real-life community of believers she claims to be a part of, then she could be considered an anomaly and disregarded as such. But it’s not always possible to do that, even for Christians. And for moviegoers without a strong understanding of Jesus and his supreme love for His children, it’s far too easy to walk out of the theater with a slightly thicker wall erected against the things of Christ. That’s a poison far more lethal than any flower could ever be, even the famed white oleander.