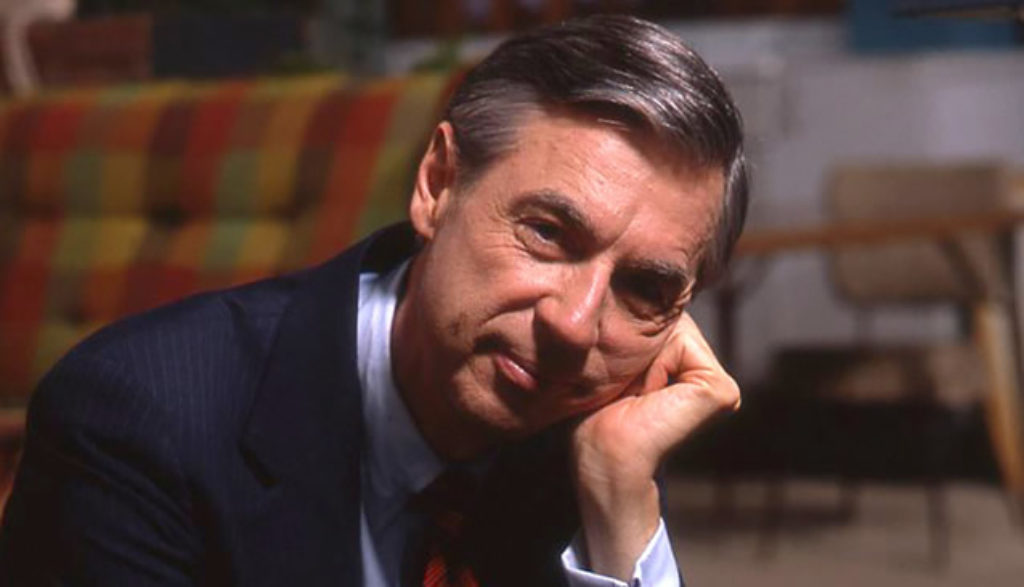

Fred Rogers hated television.

When he talks about his first encounter with the still-infant medium, he doesn’t hide his distain: “They were throwing pies at each other,” he says.

Over the next several decades, they’d throw a lot more than pies. Characters would throw insults and expletives, punches and grenades. In all his years working inside the medium that so horrified him, he never succeeded making it much better.

Well, except, of course, for his own little corner of it: Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

It was a crowded place, this neighborhood. Beginning in 1968, Rogers’ welcomed countless children into its gentle confines. They gathered in his television house (courtesy their own TV sets) and watched him walk in, slip on a sweater and take off his loafers. He’d talk with Picture Picture, visit with a friend or two and all hop on a trolley to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. No pies. No car chases. No angry arguments or slamming doors.

Some adults couldn’t see the attraction. But it wasn’t for them.

The documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, directed by Oscar-winning documentarian Morgan Neville, takes viewers by the hand and leads them, not into the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, but into Rogers’ real world and the real concerns he tried to address—as teacher and preacher, puppeteer and singer. And most of all, as a neighbor.

“You take all of the elements that make good television and do the exact opposite, you have Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” show producer Margy Whitmer says in the doc. And indeed, few shows dared attempt the radical gentility that Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood did. The pies have always been easier. Rogers’ influence on television, entertainment and culture, at least on the surface, seem negligible.

But somehow the show survived and endured. Now, 15 years after Rogers’ death and 50 years after his show came to be, in an age more callous and cruel, the show and the man behind it feel more relevant than ever. And as the documentary suggests, perhaps Rogers’ influence wasn’t so negligible after all.

This film makes the case—and a convincing one—that Fred Rogers was an American hero, albeit one who eschewed capes for cardigan sweaters. If he was a hero, it begins with this: He was exactly who he seemed to be.

That in itself is remarkable in this age of scandal and fallen heroes. Interviewees in the documentary testify again and again to Rogers’ consistency of character, his essential goodness. And while I’m sure he had bad moments like anyone else (one of his sons says that, if he was about to say something un-Mister-Rogers-like, he’d say it in the voice of Lady Elaine, gadfly of the Neighborhood of Make-Believe), his public persona seems amazingly consistent with his private self.

He clearly cared for other people, too—and not in just a passive, courteous sort of way. He was almost frightening in his sincerity. His biggest fans were folks too young to tie their shoes and were not, perhaps, the most scintillating of conversationalists. But he never seemed to look past them or check his watch when talking to them. He would take each one of them as seriously as he would an adult—and that was one of the keys to his success.

Rogers took his job incredibly seriously. The doc tells us that there was precious little ad-libbing on the set: Rogers’ wanted every word to be carefully considered, and he labored intensely to make sure that every message and every song was on point.

And what were those messages? Won’t You Be My Neighbor? tells us that Rogers was an activist, albeit a gentle one. When southern hotel owners were pouring caustic cleaning agents into pools to force African-American swimmers to get out of them, Rogers was dipping his toes in a wading pool with the Neighborhood’s black Officer Clemmons. Whenever he thought that his young viewers might be worried about a real-world issue, he’d address it in his show. He themed programs, even whole weeks, to deal with everything from war and assassination to grief and divorce. Some critics paint Rogers as a Pollyanna, a milquetoast spokesman who ignored the real world outside the confines of his “neighborhood.” The documentary suggests he was anything but.

But perhaps the most important messages he wanted to convey was that he liked his young viewers “just the way you are.” While some critics suggested that Rogers’ focus on messages of uncritical self-love and acceptance helped usher in a world of pampered snowflakes and soccer games where no one keeps score, that wasn’t his purpose at all, the film suggests. He simply believed that if people felt that they were both loved and lovable, they’d have the confidence to do tremendous things.

“Love is at the root of everything,” Mister Rogers says in archival footage from the doc. “All learning, all relationships. Love, or the lack of it.”

Rogers’ critical messages of love, incidentally, sprang from his own deep Christian faith. In the movie, psychology professor (and co-director for the Fred Rogers Center) tells us that his philosophy was about mirroring God’s own unconditional love for His children: “You are the beloved son or daughter of God,” he said.

Rogers was also an ordained minister, and a fellow pastor in the movie says that the television was his pulpit. Rogers didn’t just teach from his television set: He preached, the pastor tells us—not explicitly Christian theology, of course, but a moral framework dependent upon Rogers’ understanding of Scripture and God. He considered the space between his cameras and his viewers’ eyeballs to be “holy ground,” a sacred space where deep conversation could take place.

We also learn that Rogers’ read the Bible constantly. And toward the end of his life, he turned to Joanne, his wife of more than 50 years, and asked her, “Do you think I’m a sheep?” He was referencing Matthew 25, which describes God separating those who know Him (the sheep) from those who don’t have a relationship with Him (the goats). Joanne reassured him that if there ever was a sheep, Mister Rogers was certainly one of them. Elsewhere, one of Rogers’ sons jokingly calls him a second Jesus—someone who could apparently do no wrong.

Though there was certainly never any sexual content in Rogers show, there’s actually a bit of it in the documentary. François Clemmons, who played Officer Clemmons in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, identifies as gay here. He talks about how he visited a gay bar at least one night while part of the show, and how word got back to Rogers. Rogers told him he couldn’t ever do that again and still be part of the show. It’s inferred that Rogers’ forbid the visit for practical rather than moral considerations: To have an openly gay man as part of a children’s show would, in the 1970s, threaten the show’s funding. Clemmons later got married to a woman, but the marriage failed. “I discovered you can’t pray it away,” he says.

Clemmons says that years later, Rogers sang “I like you as you are” to him on the show. Clemmons told Rogers that it felt personal, like Rogers was singing it right to him, telling him in essence that it didn’t matter to Rogers that Clemmons was gay. Rogers told him that he was singing personally to him; in fact, he’d been singing the same message to him for two years, but Clemmons had only just heard it as Rogers intended.

We see snippets from a Tonight Show spoof on Mister Rogers, where “Rogers” (played by host Johnny Carson) pulls a scantily clad woman from the closet. “Can you say hooker?” Carson says. A crewman for Mister Rogers says that he regularly took pictures of his exposed rear with other people’s cameras as a joke. He did so with Rogers’ camera, too. Rogers never said a thing … until months later when he trotted out a poster-sized blow-up of the picture during a cast and crew get-together, an image we also see.

During Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood’s very first week on the air, Rogers tackled the subject of war (knowing many of his young viewers would’ve heard of, and been scared by, news of the Vietnam War). We see characters in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe in military uniform and carrying guns.

Audiences see news clips from that war, as well as footage from Robert Kennedy’s assassination (which Rogers also addressed on the show).

Rogers also listens to the concerns of young children who’d witnessed painful violence or death in their own lives (including the untimely death of a pet), and he talks about those concerns.

We see footage from a comedy show depicting Rogers and famed chef Julia Child in a no-holds-barred professional wrestling contest. (Child has the upper-hand early on, but Rogers seems to make a comeback after he pulls out a King Friday puppet.)

Several profanities are heard—uttered by people other than Rogers, of course—including three uses of “a–.” We also hear “b–ch,” “b–tard,” “d–n,” “d–k” and “f-gs.”

None.

None.

If the secular world was prone to crown its own saints, Mister Rogers would make the cut. Few folks have anything bad to say about the guy these days—a bit different from his heyday when his gentle manner and the show’s unchanging format made Rogers an easy target for satire and ridicule.

Back then, Rogers’ very kindness was used against him. Now we miss him. His gentleness seems like an antidote for troubled times.

Sometimes in our complex world, we imagine that all deep truths must be equally complex. We twist our sciences and philosophies and even theologies in knots, imagining ourselves growing deeper as our logic grows denser.

We can make that mistake in art, too: The most critically praised works of film and television and game are often dark, bleak works as well. It’s often implied that if entertainment is dark, it must be deep as well, its grit and gloom a certification of quality. We don’t throw many pies on TV anymore. We throw souls, hoping that when they hit, audiences will feel something. Anything.

To that, Mister Rogers sidles up beside us, looks deep into our wary, weary eyes and seems to say, simply, No. The secrets of life aren’t found in the darkness. They’re found in God’s beautiful creation, which we should always look at with a childlike sense of wonder. They’re found in the beauty we see in ourselves, majestic (though tarnished and fallen) creations of a just, merciful Creator. And most of all, they’re found in love itself.

This documentary won’t make everyone feel like singing, as noted in the content sections above. Still, for many, its core message will resonate even if some particulars aren’t just right.

Following the release of Won’t You Be My Neighbor?—a documentary being praised in every corner, it seems—I read the same sentiments again and again. We need Mister Rogers, they say. More than ever, we need Rogers’ kindness. Respect. Love.

But it seems to me that if Fred Rogers were still around, he’d say that what the world needs is … us. The children that he told were both loved and lovable. The children he tried to teach to be kind and respectful. The children who’ve grown up now—those who don’t sing his songs any more but who, deep down inside, remember them.

Mister Rogers is gone now. But his legacy lives on. And if Won’t You Be My Neighbor? offers something lasting, perhaps it will be to encourage us to emulate that legacy in our own lives a little bit better.

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.