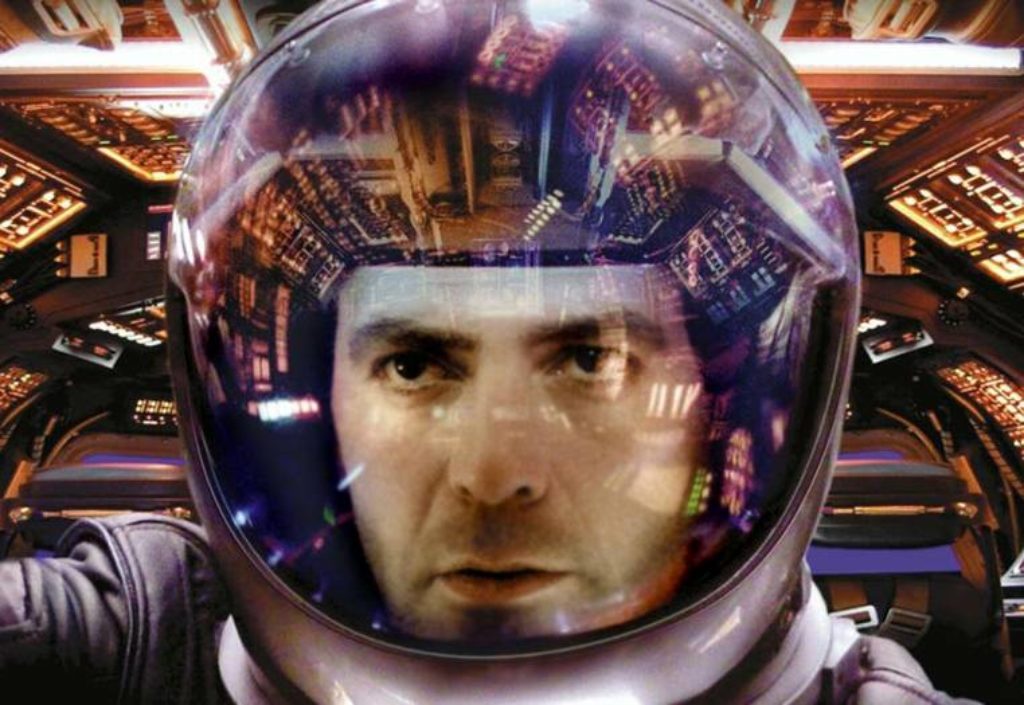

While orbiting and observing the mysterious planet Solaris, a small team of scientists comes under attack. Not by monsters. Not by marauding space pirates. The silent assault is on their sanity. Desperate to explain the bizarre events befalling his crew, the team leader transmits a cryptic video to garner the help of an old friend, psychologist Chris Kelvin. Kelvin arrives at the space station Prometheus only to find his friend frozen in a body bag—a victim of suicide. Two shipmates remain alive. One is Helen Gordon, a rational, no-nonsense woman convinced there’s evil afoot. The other is Snow, a laid-back young scientist who communicates in the manner of an aw-shucks stoner unable to articulate a disjointed stream of consciousness. They’re the lone survivors. But they’re not alone.

By reading the crew’s idle thoughts, memories and dreams, the celestial force of Solaris has been incarnating flesh-and-blood recreations of people from their past. Why? Should these ‘visitors’ be feared or embraced? The emotional center of the story arrives in the form of Rheya, Kelvin’s beautiful wife whose suicide still haunts him. She simply appears out of nowhere, oblivious to her death and ready to pick up where they left off. But it’s not really Rheya. This woman is simply the embodiment of Kelvin’s recollections of her. She has Rheya’s memories, yet feels strangely disconnected from them. Even so, her love is sincere, and that’s good enough for Kelvin who, believing he has been given a second chance, wants to make things turn out differently this time.

“The theme of predestination is crucial,” Soderbergh says. “Kelvin and Rheya’s relationship ended very badly. When she appears on the Prometheus, they both struggle with the idea of the relationship traveling the same path it did before.” To help us better understand that path, Soderbergh sprinkles in many glimpses of their courtship and marriage via flashbacks.

Instead of solving the mystery of Solaris, Kelvin becomes ensnared by it—seduced by the prospect of love and redemption. Can Kelvin and the other crew members regain perspective? Is Solaris to be feared? What force is behind all of this? What does it hope to gain? What purpose do the visitors serve? What are the implications for Earth? Anyone going into the film expecting answers to these questions will emerge disappointed. Queries abound. Logical resolution is in short supply. Directed by Steven Soderbergh and co-produced by James Cameron, Solaris is solemnly paced psychological science fiction totally unlike the two men’s mainstream hits Erin Brockovich, Traffic, Titanic, The Terminator or Aliens. It remains to be seen whether audiences are ready for it.

positive elements: Several snapshots of Kelvin and Rheya’s courtship are sweet and selfless. He affirms her in ways her parents never did, and encourages her to follow her dream of becoming a published author. Rheya’s psychological challenges testify to the damage done by an emotionally abusive home life. Instances of suicide are reflected upon—with the victims’ own hindsight—as tragic miscalculations. The film raises issues of mortality, God, eternity and the power of choices to shape one’s destiny. A poignant moment finds the “new” Rheya unable to see herself as anything more than the sum total of Kelvin’s perceptions of her (a reminder that how we value others can have a strong impact on their self-image and, in turn, the person they will become).

spiritual content: We eavesdrop on a dinner-table debate over the existence of God, during which Kelvin argues, “The whole idea of God was dreamed up by man.” He’s a nihilist who contends that the evolution of mankind was an inevitable probability. Meanwhile, Rheya can’t wrap her mind around it all, yet insists that man is somehow unique and not a cosmic accident (though the notion of a loving Creator doesn’t factor into her belief in a higher power). Upon being reborn as a visitor, Rheya still has a yearning to connect with the essence responsible for her existence (“It created me, yet I can’t communicate with it”). Her desire to have fellowship with her creator reflects a basic need of the human soul, conceived by God (Gen. 1:26-30), satisfied through Christ (2 Cor. 5:16-21) and fulfilled perfectly in eternity (John 14:1-4). The final line of a Dylan Thomas poem, “. . . and death shall have no dominion,” appears periodically (Rheya even clutches it in her lifeless hand after committing suicide). While that line is true in a biblical context (1 Cor. 15:50-55), the way it is embraced in Solaris simply leads viewers to believe that death is not something to fear, but may actually provide release into personal nirvana. [Spoiler Warning] In the end, as the Kelvins reunite on “the other side,” Chris asks the awaiting Rheya, “Am I dead or alive?” She responds, “We don’t have to think like that anymore. . . . Everything we’ve done is forgiven. Everything.” A nice concept, but precariously incomplete. While that’s true for the person who has accepted Christ and expressed repentance (1 John 1:9), someone who hasn’t could walk away from Solaris deceived into thinking that such bliss awaits everyone grappling with eternal issues, regardless of what they believe (after all, Kelvin is a card-carrying atheist and he got in).

sexual content: George Clooney’s bare backside gets more screen time than some of the film’s minor characters. One scene shows Kelvin and Rheya chatting in bed, lying nude on their stomachs. Elsewhere, tighter shots show the couple tossing about in the throes of passion. Most disappointing of all, Kelvin’s recollection of the night he and Rheya met concludes with passionate kissing and an image of him standing naked (full view from behind) as they embrace prior to sex.

violent content: There’s no “violence” per se, but rather the residue of violence. [Spoiler Warning] Kelvin follows a trail of blood and discovers corpses. Snow talks about a deadly encounter between a human and his visitor lookalike. Rheya alludes to having had an abortion, then ends her life with pills when her husband walks out in anger. The “new” Rheya is distraught enough to drink liquid oxygen, which leaves her scarred and lifeless—temporarily. Kelvin coldly jettisons a visitor into deep space.

crude or profane language: Fewer than a dozen profanities, though they include several misuses of God’s name, five s-words and one f-word.

drug and alcohol content: Kelvin and Rheya drink alcohol at a party. On separate occasions, pills are taken to control sleep or invite death.

other negative elements: Gordon suggests that the visitors must be humanely disintegrated. Kelvin argues that would be murder, to which she replies, “We are in a situation that is beyond morality.” Can any situation be considered truly “beyond morality”?

conclusion: Here, Academy Award-winning writer/director Steven Soderbergh is an archer aimlessly firing philosophical arrows into the air in hopes that he’ll hit something (which occasionally he does). Some in the crowd will gasp and applaud his unconventional style, taking great pleasure in trying to figure out what he’s thinking and why he’s turning one way or another. But most will check out after the first quiver. Without a target, this ambiguous intellectual exercise gets tedious. Many viewers will leave the theater more frustrated than fascinated.

Star George Clooney says, “What makes Solaris relevant today is that it deals with the basic issues we constantly question and wonder about: love, death, after-life. The things we don’t have any answers to. We want to define things and those things we can’t define terrify us. We want to know how high is up, how old is eternity. Everything we know as humans has limits—a beginning, middle and an end. No one in this story has answers. They just have really good, smart questions.” But the ponderings are rudderless. The filmmakers seem as confused as the characters in the story. And for people who aren’t baffled or terrified by life’s most relevant mysteries—namely Christians who understand their personal, omnipotent Creator—the onscreen ruminations will seem empty at best. If there’s a silver lining, it’s that Solaris does offer some insight into the unredeemed mind’s desperate attempt to make sense of things on its own.

On a less spiritual note, the movie generates curiosities about characters and their ‘visitors,’ but never follows through on them. It’s one thing to leave questions unanswered about the nature of the universe; it’s another to get audiences to invest in a scenario and then leave them hanging. I attended a free sneak preview of Solaris and listened to several members of the capacity crowd share their feelings with the studio’s official opinion-taker as they filed out. Perhaps “vent” their feelings would be more accurate. If what I overheard is any indication, Solaris will open big thanks to Clooney and Soderbergh, then get hammered by poor word of mouth.

Eschewing the action, aliens and intergalactic shootouts of modern sci-fi, Soderbergh has nobly put his Oscar clout on the line in an attempt to create an artistic, understated film akin to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the end, however, the leaden, flashback-muddled Solaris will be remembered more as the film in which George Clooney bared more than his soul.