In dreams we fly. We fall. We tell off the boss. We walk to class naked. In dreams, we’re unfettered by reality, yet enslaved by love and desire, fear, sin and guilt. Dreams can be so terrifying we wake up screaming, so wonderful we never want to wake up at all.

You might be tempted to say that Cobb has a dream job, but you’d only be half right. Paid to extract secrets from the subconscious, Cobb is a gray matter thief—a roustabout whose livelihood is as shady as the worlds in which he walks. His methods, as bizarre as they seem, are curiously rote: He and a team of specialists “build” a dream for their subject—often a titan of industry with corporate secrets locked away in his brain. Using a concoction of drugs, they render him unconscious, and he slips into the dreamscape they’ve painted for him. Then Cobb and his partners dive into the same dream, extracting information in such a way that, if all goes well, the guy might not even remember in the morning.

Cobb sells his unusual skills to the highest bidder until, after a botched job, the subject pitches a new sort of subterfuge: Instead of extracting ideas, could he plant one? Could Cobb sow a conceptual seed that would cause a corporate heir to dismantle the family business?

Most dream-thieves like Cobb would say such a thing is impossible. The subconscious mind knows when it’s being tampered with too much. Cobb, though, knows it can be done. He’s done it before—though it cost him everything.

Now, this former subject—Saito, by name—is offering Cobb’s “everything” back: The chance to go home, the chance to be a father again, to see the children he was forced to leave so long ago.

Home. Family. Those are the things of Cobb’s dreams. And, after spending most of his adult life living in other people’s, Cobb finds that he will stop at nothing to make his own come true.

Cobb is a man who lives in the shadows—indistinct, conflicted, haunted by guilt. But he is at his most distinct—most alive—when it comes to his children. In fact, the very idea of seeing them again drives him to take outlandish risks.

Those risks manifest themselves in less-than-desirable ways. And he forces his team to take those same risks without giving them all the necessary information. But the film doesn’t make Cobb out to be a hero. Instead it asks us to seriously grapple with his questionable decisions. And that, perhaps, marks Inception’s greatest strength.

Saito says that planting this new idea into his rival’s mind is a “good” thing, because if the energy corporation he owns doesn’t break apart, it’ll have a monopoly against which no other company could compete. “The world needs Robert Fischer to change his mind,” Saito says. But would any good ever justify playing with someone’s brain in such a manner?

Cobb tries to help Fischer come to some sort of subliminal reconciliation with his now-dead father. Motives aside, is such a reconciliation desirable, bringing a son a sense of familial peace? Or is it terrible, because the reconciliation—regardless of how it makes the subject feel—is false?

Inception allows, even encourages us to ponder these things—but we have to drill beyond its caper conceit.

While Inception steers well clear of overt religion or faith, its surreal, metaphysical environs throw viewers into a world that actually feels quite spiritual. The dreams we see can resemble private hells, filled with self-reproach and regret and demons of the dreamer’s own making. (Characters refer to one undesirable state of unconsciousness as “limbo.”) As Cobb tries to free himself from his own guilt and grief, his catharsis feels both psychiatric and religious: He confesses a past mistake that wound up having horrific consequences; he confronts those consequences; he eventually exorcises, in a strange sort of way, his personal tormentor.

Elsewhere, someone says that he and his former love “felt like gods” after living in a dream state for (in dream time) years, creating the world around them as they saw fit.

Cobb and Saito first meet in a “love nest” where Saito frequently meets his lover—a relationship he’s managed to keep secret in his waking life. We see people kiss, and one character uses subterfuge to steal a kiss. A couple of women wear low-cut tops.

Violence in Inception is tricky to tally. At times we see real men get hurt or killed. But much of the violence is perpetuated in dream worlds, where the people we see are not real, but manifestations of the subject’s subconscious. As a result, the “real” body count is surprisingly low (at least for a film that wields this much intensity), while metaphysical fatalities run off the chart.

Merging both categories, people are punched, kicked, choked, shot (scores of times), stabbed, hit by cars (several times), blown up, attacked by rampaging mobs, almost buried by avalanches and nearly drowned. Somebody gets shot in the foot—just to illustrate that, while dying in a dream state is difficult, pain is all too easy to come by.

The visceral feel of the violence is about what you’d expect for a PG-13 movie—and, frankly, maybe a step back from a prime-time actioner on television. The mayhem is practically bloodless (an exception: after a shot to the chest, we see red seep through a man’s shirt as he coughs up flecks of blood), and it’s perpetrated with a certain, almost chilly, remove.

When someone wants to exit a dream, they simply “kill” themselves or have someone do it for them. Cobb, for instance, shoots one of his compadres in the head to wake him up. (We see a bloodless hole in his forehead.) Because the sensation of falling can jar someone awake, folks routinely engineer the end of their dreams by plummeting off bridges or cutting loose elevator cables. One character throws another off a cliff.

[Spoiler Warning] This fixation with dreamscape suicide manifests itself in tragic fashion with Cobb’s wife, Mal. The two of them slip into a dream state for, seemingly, decades before Cobb begins to think that perhaps both of them have gotten lost there. He plants an idea into Mal’s brain—a true one, in this case—that the life they’re “living” is not real, and he encourages her to commit suicide with him. They both lay their heads on a railroad track as a train rumbles toward them. (The scene ends just before the train reaches them.) The act jars them both back to what is, apparently, the real world … but Mal can’t shake the feeling that this life, too, is still a dream—including their two children. She begins to fondle knives and begs Cobb to enter another suicide pact with her so they can see their “real” children. Cobb, of course, refuses. Then, on their anniversary, Cobb finds Mal on a ledge, ready to jump. “I’m going to ask you to take a leap of faith,” she tells him, adding that she fabricated evidence that, should she die, would frame Cobb for her “murder”—her way of encouraging Cobb to die with her. Then she jumps.

Characters abuse Jesus’ name five or six times and God’s a dozen times—pairing it with “d‑‑n” another half-dozen. We also hear “a‑‑,” “h‑‑‑,” “b‑‑tard” and “bloody.”

Folks drink wine and beer. Intravenous drugs—sedatives and other mysterious concoctions—are required to put people into these dreamlike states.

Perhaps the most nefarious drug here, though, is the dreams themselves. It’s suggested that these artificial dream states are, in some way, addictive. In one scene, we see listless bodies strapped to machines pumping dream-causing chemicals into their bodies. We’re told it’s the only way they can dream anymore, and for them, an old man says, “The dream has become their reality. Who are you to say otherwise?”

Cobb, too, has lost his ability to dream normally, and so he repeatedly hooks himself up to delve into his own haunting dream world.

Let’s reemphasize here that Cobb is a thief—a reluctant one, perhaps, but a thief nonetheless. He steals thoughts for a living. And he’s not alone. While the characters seem to care for one another (to a point) and we see much of Cobb’s desire to be with his family, the finer points of morality seem to have eluded this crew. And while, as I noted earlier, it’s a positive thing to think through ethical dilemmas, this movie won’t help you arrive at the right conclusions. We, as moviegoers, must on our own consider and judge their motives, because these characters themselves do precious little of that.

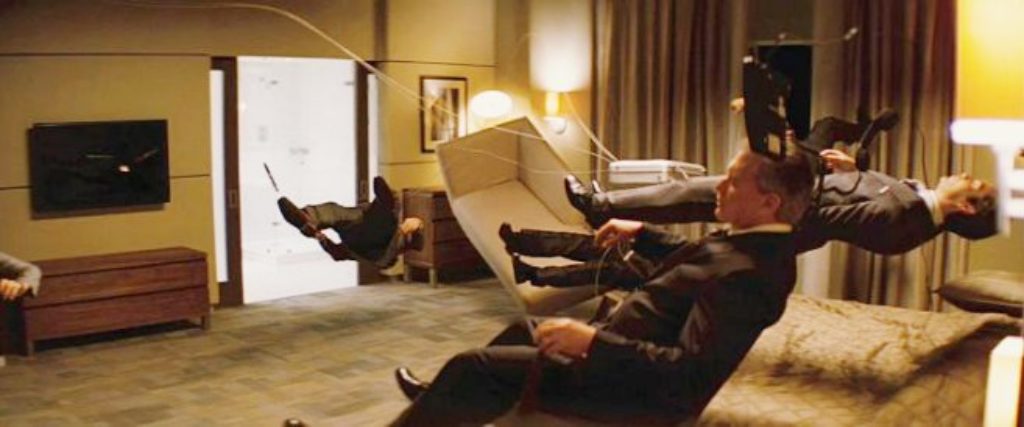

The concept of a dream within a dream is an important one for Inception. Cobb and his cohorts construct dreams like nesting dolls to confuse their subjects. Wake up, you’re still dreaming. Wake up again, and you may be dreaming still. Each dream-layer accesses a deeper level of subconscious.

A proper critique, then, demands the same treatment.

Layer 1: Artistically, Inception is one of the year’s most provocative, compelling films. The story’s the thing here—so strong that the film’s topnotch cast and stunning visual effects serve it without overwhelming it. Directed by The Dark Knight’s Christopher Nolan, Inception aspires to art without relinquishing its popcorn-munching bona fides. It’s a film that’ll likely resonate with critics and moviegoers alike.

Layer 2: Inception’s content centers on its suicide-fueled violence—which trivializes the act of self-annihilation. In doing so, we’re forced to a place where, looking through the eyes of some characters, suicide appears to be a convenient, beneficial out from a reality you don’t want anymore: Let’s scrap this world, because the real one—presumably a better one—lies beyond. In this ethos, suicide isn’t an act of desperation or despair, but one of hope and promise. So I can’t help but wonder how someone who is already toying with the idea of ending it all would view this film—if they might look through the eyes of a “suicidal” character and find their own tragic longings mirrored there.

Layer 3: We see no heroes here—not really, anyway. Rather, we meet a cadre of thieves without scruples—breaking not into a house or a car, but into the human mind itself, the throne room, if you will, of the soul, of our thoughts, of our ability to love. Dwell on this for even a short while, and Inception’s central premise begins to feel hopelessly damaged. Our onscreen protagonists are more than burglars, after all. They’re intellectual rapists, ravishing and despoiling the very thing that makes us us.

Layer 4: Leveling the plot-driven accusation of mind-rape still doesn’t tell the whole story. Because Inception seems to understand that it’s walking on a pretty thin tightrope. It doesn’t try to excuse or apologize for Cobb. Rather, it places him in a circle of Dante’s hell. He steals as his life was stolen. He suffers as he caused suffering. He creates his own realities while destroying what’s real. He walks in dreams more tangible—more important—than his waking life. All the while he asks without asking:

What is this? Why am I here? Is it worth it? Is there something more?

Paul Asay has been part of the Plugged In staff since 2007, watching and reviewing roughly 15 quintillion movies and television shows. He’s written for a number of other publications, too, including Time, The Washington Post and Christianity Today. The author of several books, Paul loves to find spirituality in unexpected places, including popular entertainment, and he loves all things superhero. His vices include James Bond films, Mountain Dew and terrible B-grade movies. He’s married, has two children and a neurotic dog, runs marathons on occasion and hopes to someday own his own tuxedo. Feel free to follow him on Twitter @AsayPaul.